World War II

The declaration of war in September 1939 did not result in the same wave of patriotic euphoria of 1914. But nor did it take anyone by surprise.

Emmanuel, along with other Cambridge colleges, had been preparing for hostilities for some time. As early as May 1938, the Bursar had been appointed Air Raid Warden. The College had also purchased the necessary fire fighting equipment by September. A watchtower was set up on the roof of Front Court and from here the fire-watchers were on duty from the war's first day. All College members received instruction in fire fighting & the regular Air Raid Precaution drills. Happily, the only bomb damage the College suffered occurred on 16 January 1941, when a small device fell on the kitchen roof. It was extinguished ‘quite easily’ by the two students on duty: Ronald Ruddle & Paul Fehrsen.

The College’s silverware, archives, ancient stained glass and handful of pictures & rare books were evacuated shortly after the war began. These trusted keepers were mainly Emmanuel clergymen in the countryside. The blackout was strictly enforced: one student later vividly recalled the hazards of crossing Parker’s Piece in the pitch dark!

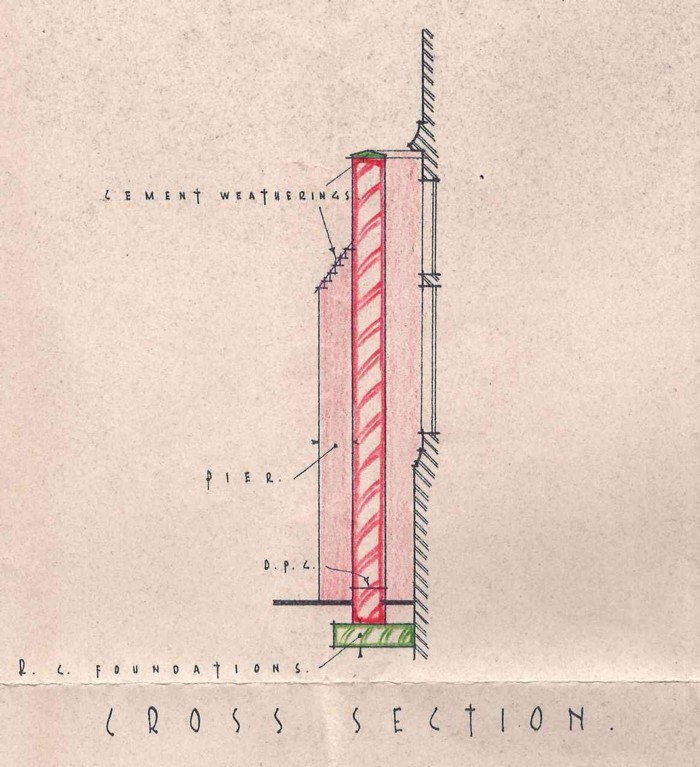

As the war progressed, the parapets where the fire-watchers sat were reinforced, and sandbags & brick screens covered the College's windows. Many basements were used as air-raid shelters, and a new refuge was built in the gardens of 55 St Andrew’s Street. The tunnel under Emmanuel Street was reinforced with strutting to provide another shelter.

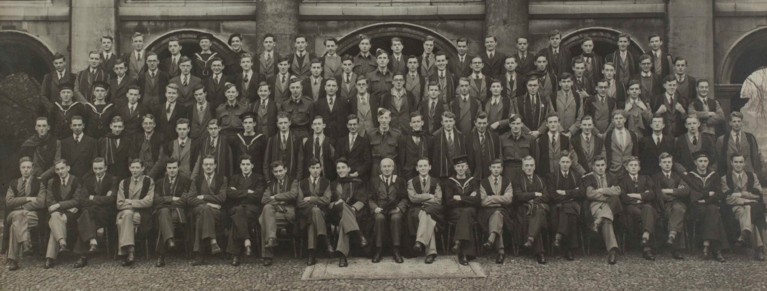

Recruitment for WWII was organised by the army in a much more considered way. Therefore numbers of students, staff & Fellows were not reduced to anything like as in WWI. Annual admissions were much higher for most of the war years than they had been in the 1920s. However, as many students were only at College for a short time, the number of resident students fell. Arts students could study for a year before joining up. Scientists & engineers were awarded their degrees after only two years. Intake included many RAF, Royal Navy & Royal Engineers 'short course' cadets, who took six-month courses in arts, science or engineering. These men were housed in North Court, which was again, as in WWI, given over to the army. The RAF also used parts of Emmanuel House & the Hostel as Sick Quarters.

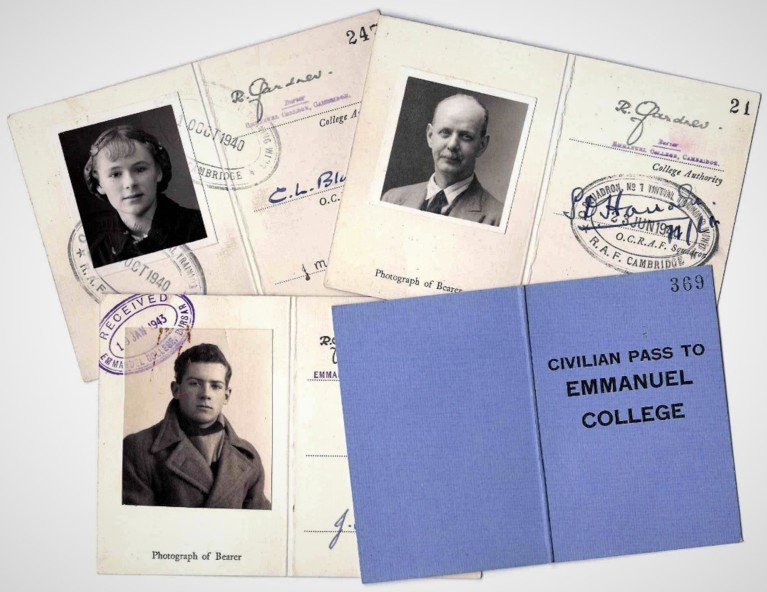

From July 1942, the RAF were given permission to use the squash courts for the disinfection of blankets. Because of the military's presence in the College, Fellows, students & staff had to be issued with civilian passes for access. The railings along St Andrew’s Street were sacrificed to the war effort in 1940. However, after a tussle with the Ministry of Works & Buildings, North Court's railings were restored, in the interests of security.

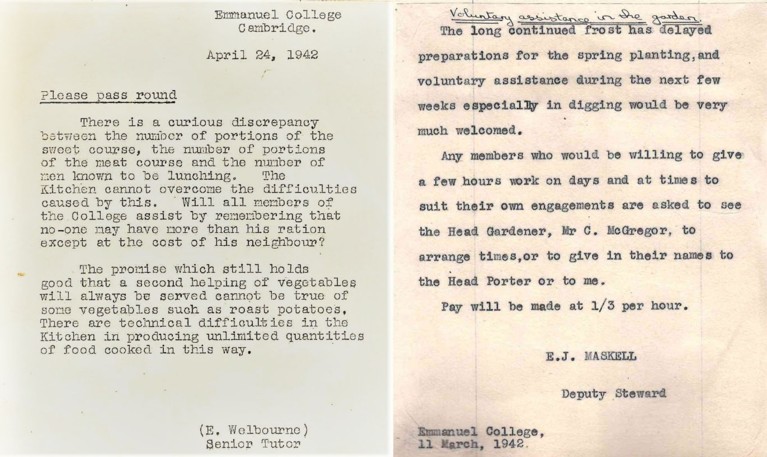

Due to the strict rationing of food & fuel, the domestic side of College life was markedly affected. An endless stream of Ministry of Food directives were issued to Cambridge colleges. These minutely controlled quantity & ingredients, and employed specific suppliers. The quality of food served at Emmanuel suffered significantly, due to both rationing and the departure of its skilled cooks. Therefore there were many complaints about the food! One student describing a especially awful dinner as ‘one of the foulest meals within human history’. The wartime menus are filled with off–putting items such as kidney omelette, calf’s head vinaigrette, egg cutlets & marrow jam tart. In an attempt to improve the quality of meals, the College cultivated its own vegetables. Initially confined to existing flower beds, in October 1940 this was expanded to neat vegetable plots across the Paddock. Students were employed in both the kitchens & gardens, and maintained the vegetables until 1949, as rationing continued after the war.

The social life of the College's undergraduates & 'short course' cadets was less seriously affected than in WWI. This was due to student numbers remaining fairly high throughout the war. Sadly rationing made things like tea & sherry parties — formerly staples of student events — impossible. However, they were able to enjoy any sports still on offer. There was rowing three days a week, and the squash court was in regular use. The Wilberforce Road sportsground was shared with local Cambridge schools from 1941, and grazed by sheep during the summer vacation. The Debating Society held meetings throughout, often discussing issues about the conflict, and the Musical Society were able to continue to give concerts. Sadly, the Dramatic Society had to sacrifice the timbers of the Old Library stage for 'Civil Defence Purposes'.

Emmanuel’s Fellowship was, of course, affected by the war. A large proportion of young & older younger Fellows left to take up war work. The remaining Fellows also took on war-related duties as well as their normal teaching. Retired Emmanuel Fellows living in Cambridge were asked to take over some of the teaching, as were the visiting lecturers. One such visitor was Luis Cernuda, who would become one of Spain’s most acclaimed poets. His poem El Arbol was inspired by our celebrated Oriental Plane tree. Another visiting academic was Professor Frank Dobie of the University of Texas. He greatly enjoyed his time at Emmanuel, despite the War. Prof. Dobie later published an entertaining account of his life in Cambridge. Rarely seen without his beloved Stetson, he was a noted storyteller, and a popular addition to the College community.

The end of the War in Europe was marked at Emmanuel by modest festivities on 8 May 1945: 'V. E. Day’, as rationing prevented anything more lavish. A motion for free drinks and a Victory Ball Dinner had been proposed by the Debating Society. This was passed with a unanimous vote! Neither of these proposed options were possible. However, port from the cellars was provided for all members of the College. They toasted the King's health on V. E. Day, at a meal whose first course was the patriotic 'Consommé Rex'.

The number of graduates killed in WWII was slightly higher than the death toll of WWI. Around 140 Emmanuel men were killed on active service, or as a result of enemy action. Most who died were soldiers & airmen, although there were also more than a dozen naval fatalities. Eight Medical Officers & two Chaplains to the Forces also lost their lives. A few appear to have been killed while carrying out Intelligence work. There were also civilian casualties too, with several men dying in air raids or during attacks on passenger ships.

The memorials to our 1939–46 Fallen consist of an illuminated parchment Book of Remembrance. The College also specially commissioned a cross for the Chapel altar, which was made by Howard Brown of Norwich.