Blog

24 June 2025

Cambridge’s (in)famous ‘May Week’ attracts a certain amount of censure for its perceived excesses. The principal targets are the high-decibel May Balls and June Events, considered by some to lack the charm and refinement of former days. Well, perhaps they do, but critics may be surprised to learn that May Week had its detractors as long ago as the late-nineteenth century.

The origin of the celebrated festivities was, of course, the University’s annual Easter Term regatta, which began in the 1820s, and was originally held in May. From 1863, Trinity College held an annual May Ball, but other colleges (including Emmanuel) confined their jollities to a garden party or concert. In the 1880s, however, with student numbers on the rise, college balls began to proliferate. Emmanuel’s first ‘May Week Dance’ was held in 1892 and despite the ‘unusually cold weather’ it was such a success that the college authorities were ‘induced’ to let it become an annual fixture.

An anonymous opinion-piece in the 1891 issue of the Emmanuel College Magazine summed up the ‘overpressure’ that had already become the hallmark of the summer carnival: ‘The Cambridge May Week is unique in many ways. To begin with, it generally falls in June and always lasts for a fortnight at least. It is partly an aquatic festival in a place that has no river to speak of, and partly a series of society functions in a town that has no society. It finds no place in the Calendar, yet it is perhaps the one touch of nature that makes the whole University kin…the rowing man believes that the whole round of gaiety is but the fit setting to his marvellous deeds, [the] musical genius knows that it all leads up to his encore in his College Concert’.

The remainder of the Magazine article purported to be an extract from a letter written to a female friend by a young lady who had recently experienced May Week. Her account of the gaieties included a series of sly swipes aimed at idle students (particularly her intellectually-challenged brother), boating bores, petty academic rivalries, amorously-inclined young dons and the ‘third-rate canal’ on which the boats were raced. The blasé young Miss had dutifully attended ‘the Boat Procession, and a Polo Match, and the Pastoral Play, and Colleges and Chapels, and Libraries without end. I suppose it is only in the May Week that they are so very gay in Cambridge, but I have a suspicion that they never do work very hard’. She dismissed Trinity’s Ball as being ‘a good deal like other dances’ and expressed similar sentiments about the endless college concerts, although she conceded that at least they could be talked through, and ‘when they light up the college gardens with lanterns, as they do in one or two places, you couldn’t pray for a better place to sit out a piano solo in’. This was an in-joke, as Emmanuel’s May Week decorations usually featured ‘festoons of Chinese lanterns’.

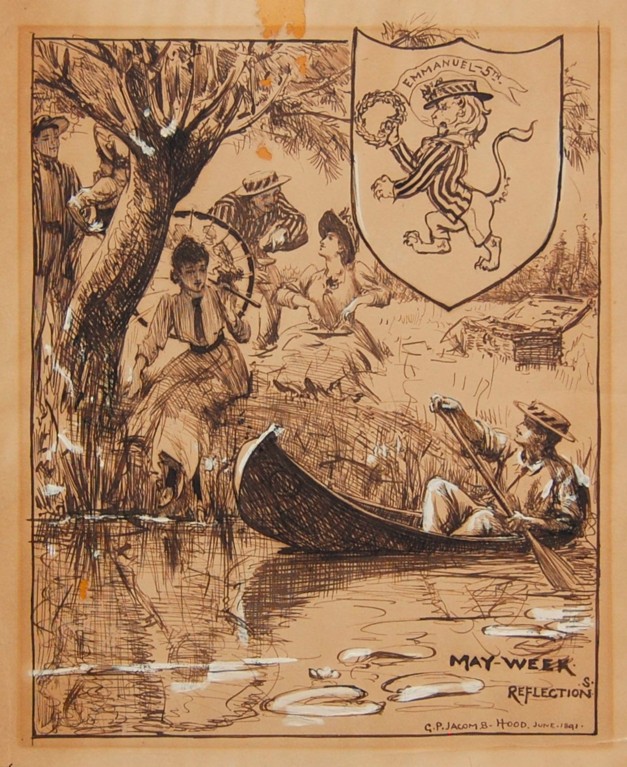

The real author of the 1891 article, whoever he was, summarised his mixed feelings by saying that although ‘after a year or two’ one May Week was much like another, it was still ‘a vital part of the glamour that hangs round a three years’ residence at the University’. The article was illustrated with a sketch by the artist George Jacomb-Hood, customised to include the Emma Boat’s 5th placing in that year’s bumps. This performance was considered by the boat club to be ‘by no means a bad one’, given that they were still getting used to their ‘new light ship’.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist