Blog

24 June 2025

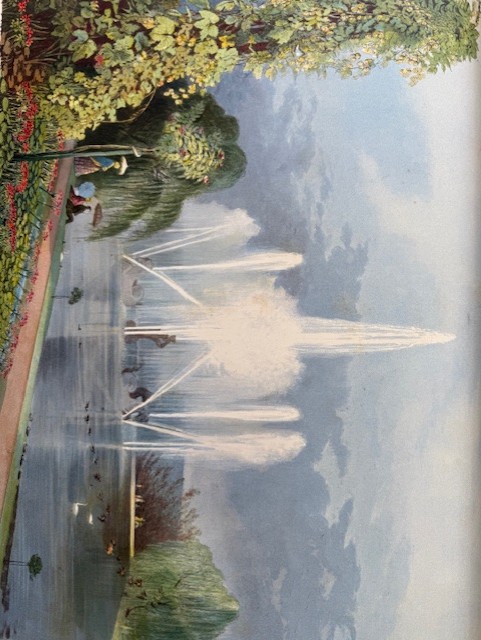

Edward Adveno Brooke, 'The Gardens of England', 'Trentham: The Lake'

Edward Adveno Brooke, 'The Gardens of England', 'Trentham: The Lake'

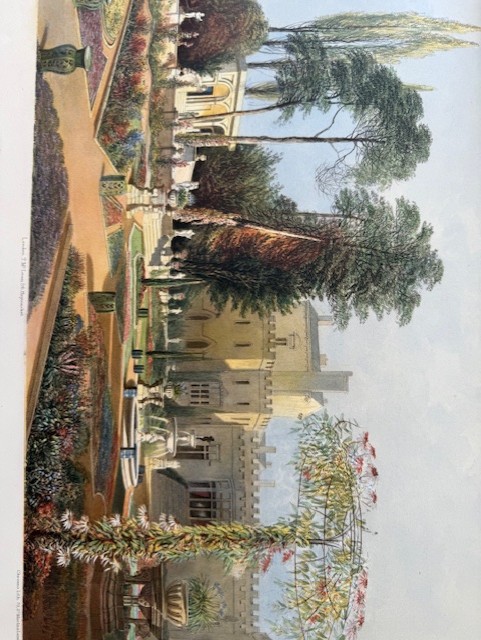

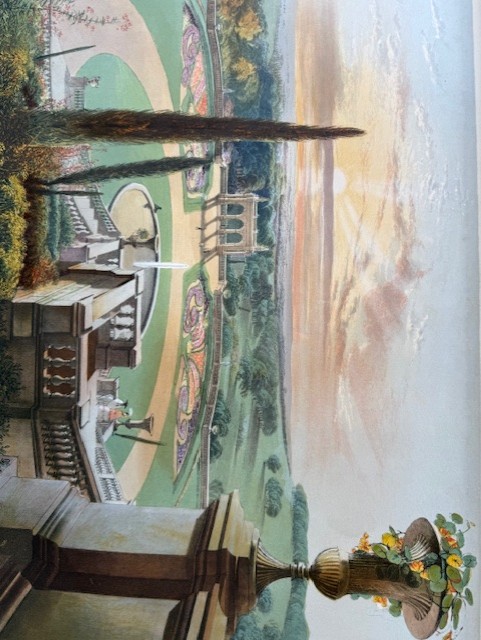

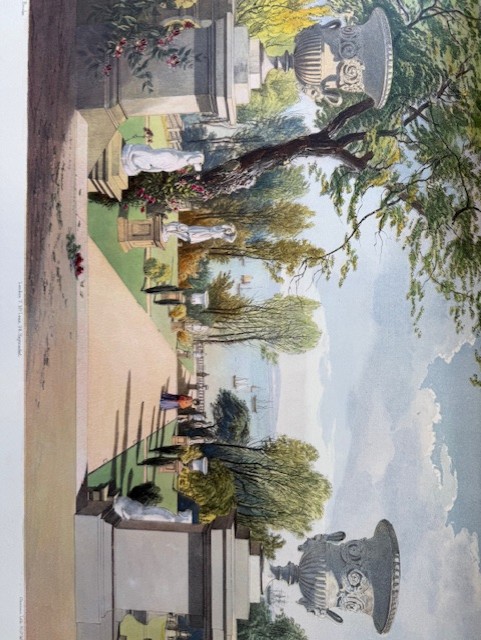

If there is one book in Emmanuel’s collection of illustrated books that presents a vision of high summer, it is The Gardens of England (1857), by Edward Adveno Brooke (1821-1910), a remarkable record of mid-nineteenth-century garden-making. The large chromolithographed plates, printed in vivid colours but finished by hand, are an invaluable record of the now largely lost world of nineteen of the grandest gardens of the age. These are gardens characterized by Italianate terraces and garden architecture, abundant urns, statuary and fountains, along with intricate parterres and massed bedding – hugely labour-intensive and requiring small armies of gardeners. The plates in The Gardens of England are a dream of beauty, each set in an eternal summer where there is as yet no sign of autumn’s damp chill. It is a dream that became a nightmare of upkeep for subsequent owners, until fashion, war, and social and economic change would sweep much of it away.

Brooke’s plate of the garden at Wilton House demonstrates the prevailing taste for juxtaposing a highly ornamented new garden with a much older house, while his picture of the ‘Alhambra Garden’ at Elvaston Castle (Derbyshire) celebrates the fondness for patterned parterres.

'Wilton House: The Parterre'

'Elvaston Castle: The Alhambra Garden'

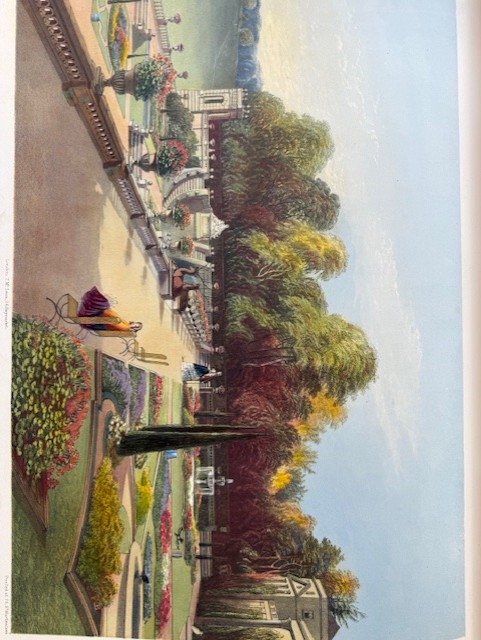

Terraces with balustrades and different levels, laid out with parterres, were added to such great houses as Bowood and Harewood, providing places for strolling close to the house.

'Bowood House: The Upper and Lower Terraces'

'Bowood House: The Upper and Lower Terraces'

'Harewood House: The Parterre'

'Harewood House: The Parterre'

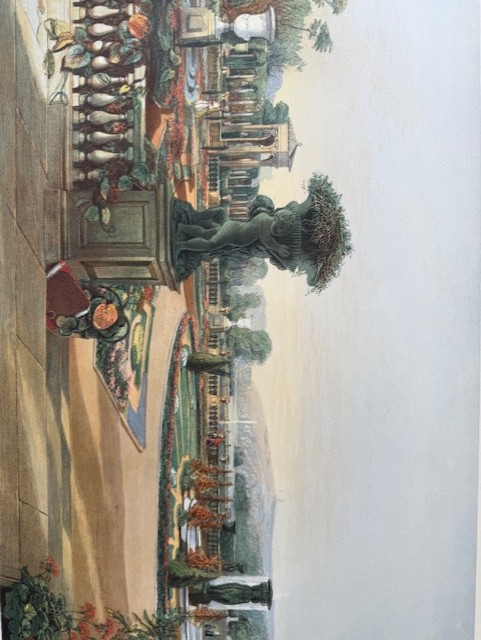

Some of the greatest estates saw the construction of the most elaborate architectural frameworks for their new gardens. At Trentham Park (Staffordshire) the wealthy Duke of Sutherland commissioned Sir Charles Barry, architect of the Houses of Parliament, to design an elaborate Italianate garden in the 1840s.

'Trentham: The Parterre'

'Trentham: The Parterre'

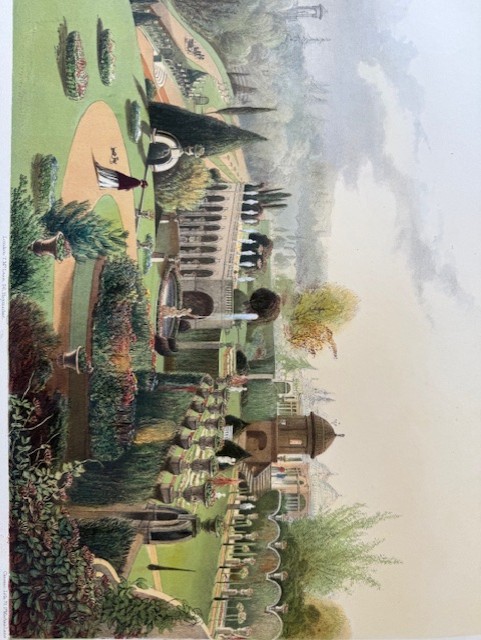

At Alton Towers (also in Staffordshire) the Earl of Shrewsbury commissioned another Italianate garden, crowded with terracing and ornaments.

'Alton Towers: View in the Gardens'

'Alton Towers: View in the Gardens'

But a more modest estate like that at Shrubland (Suffolk) would see the shaping of a whole landscape with different levels, eye-catching garden structures, and highly formal planting, in another Italianate garden designed Sir Charles Barry.

'Shrubland Park: View from the Upper Terrace Walk'

'Shrubland Park: View from the Upper Terrace Walk'

Brooke’s plates revel in the profusion of ornament, with urns and statuary so dominant that they seem to dwarf his human figures. These are landscapes in which it is the people who are the garden gnomes.

'Westfield House (Isle of Wight); View in the Gardens'

'Westfield House (Isle of Wight); View in the Gardens'

'Trentham: The Terrace'

'Trentham: The Terrace'

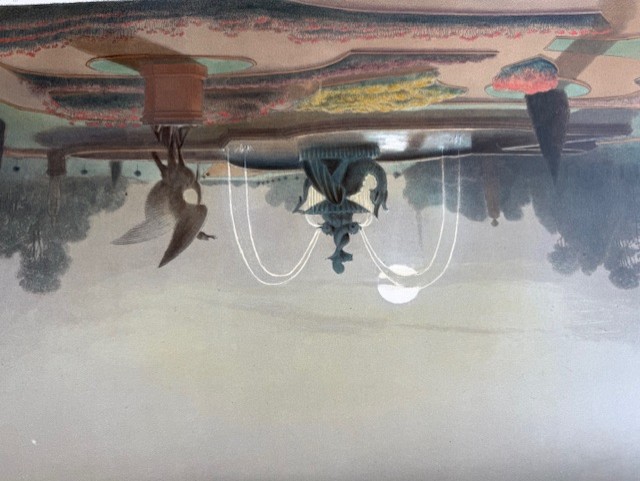

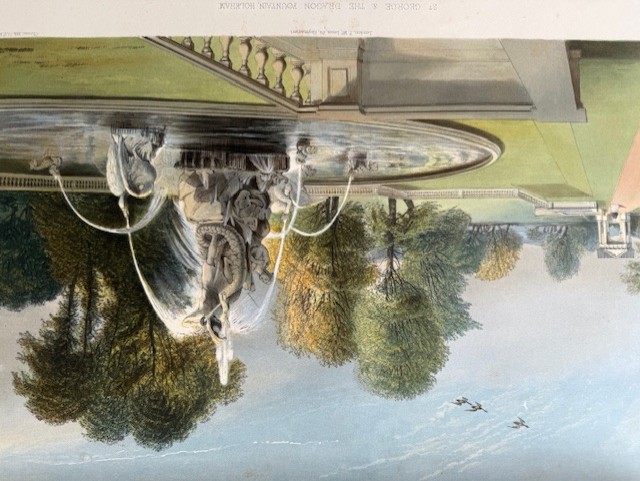

Elaborate fountains were a feature of such gardens, as in the Dragon Fountain at Eaton Hall (Cheshire) or the George and Dragon Fountain at Holkham Hall (Norfolk).

'Eaton Hall: The Dragon Fountain'

'Eaton Hall: The Dragon Fountain'

'Holkham Hall: St George and the Dragon Fountain'

'Holkham Hall: St George and the Dragon Fountain'

At Holkham as at Castle Howard, the massive Victorian fountain placed in a new parterre close to one front of the house is now part of the brand images of these houses, but Brooke’s plate showing the huge Triton fountain moved to Castle Howard from the Great Exhibition suggests how raw it must have seemed at first. At Enville (Staffordshire) a spectacular Sea Horse fountain was at the centre of pleasure grounds laid out in the 1850s just before Brooke’s plate.

'Castle Howard: The Parterre'

'Castle Howard: The Parterre'

'Enville Hall: The Sea-Horse Fountain'

'Enville Hall: The Sea-Horse Fountain'

Enville also boasted another great fountain, along with one of the most magnificent conservatories of the age: a kind of oriental palace in glass with domes and turrets (alas, demolished in the twentieth century).

'Enville Hall: The Great Fountain'

'Enville Hall: The Great Fountain'

'Teddesley House: Vista in the Gardens'

'Teddesley House: Vista in the Gardens'

Yet Brooke was well aware that a prospect down a fine avenue transcends all the changing tastes of garden fashion and always compels admiration.

Little is otherwise known about Brooke, a painter of landscapes who produced this one especially beautiful book. His preface stresses that he ‘spent several summers in undivided attention to the views contained in this volume’ and ‘made repeated visits to each locality’. But his plates show less attention to particular plants than to the visual effects of planting in form and sweeps of colour. The passage of time has lent different perspectives: the gardens that Brooke depicted so lovingly went seriously out of fashion, and those that survive are altered. Yet the high summer beauty of those gardens lives on in Brooke’s book. As he wrote of the gardens at Trentham: ‘This is fairyland indeed!’

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books