Blog

30 April 2025

M is for … Mildmay

The curriculum vitae of the Founder of Emmanuel College, Sir Walter Mildmay, is well-documented, but what do we know of his character? His portraits suggest a grave, even austere, Puritan, but there was much more to the man than that. His daughter-in-law, Grace, described him as ‘wise, eloquent…discerning…equal and just’; a man whose ‘gracious manner’ with everyone from Queen Elizabeth downwards, achieved more than any ‘harsh and distasteful speeches’ could have done. Almost every contemporary who wrote about him stressed that he was notably free from corruption and treated all men with respect, regardless of their station. The epitaphs penned for Mildmay, although inevitably fulsome in tone, seem nevertheless to express some genuine admiration. They include two particularly excruciating verse eulogies, the authors of which could not resist the temptation to make laboured puns about Sir Walter’s surname. ‘Mildmay, by name, was milde in all his deedes’, wrote Henry Roberts, while Thomas Churchyard included a touching account of Sir Walter’s deathbed, where those present ‘all gan weep, that then their jewell lost: Whiles Mildmay mildly fell a sleep, and so gave up the ghost’. Both elegists emphasised Sir Walter’s ‘zeale’ for learning. Roberts rejoiced that ‘In CAMBRIDGE Towne he late a house did frame, A Colledge faire, which hight Emanuell. Placing a manie of poore schollers there to dwell’. Churchyard soared even higher, offering the consolation that Mildmay was: ‘Not dead, death hath but broke the stamp, in Cambridg lives this knight, Where he set up so faire a lamp, that gives all England light’. Quite a lot for Emma members to live up to!

M is for … Mortmain

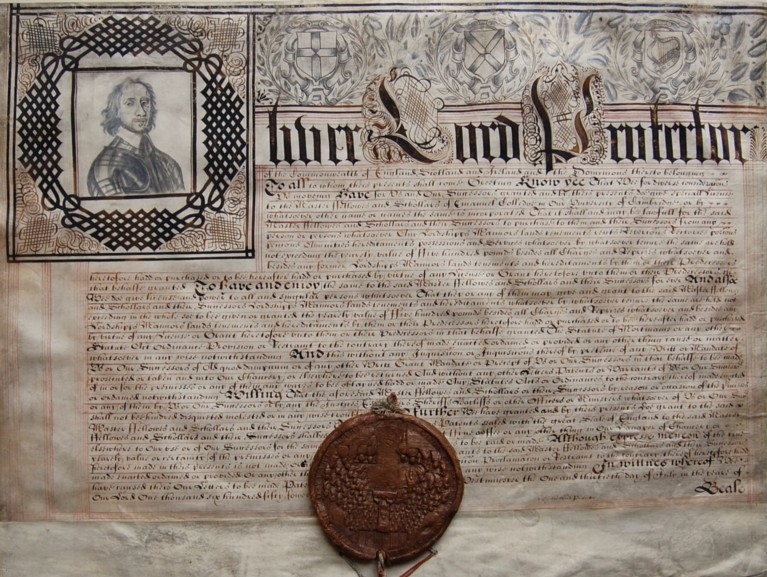

The statutes of mortmain enacted in the Middle Ages were intended to limit the amount of real estate that could be acquired by ‘perpetual’ foundations such as religious houses and university colleges, that were unlikely to put the land on the open market again. Institutions wishing to acquire real estate worth above a certain value had, therefore, to obtain a royal charter known as a licence in mortmain. Queen Elizabeth I, as a mark of her ‘abounding special favour’, had granted the newly-founded Emmanuel College the privilege of acquiring estates worth (i.e. yielding a rental income of) up to £400 a year, without having to bother about mortmain. As the price of land slowly rose, however, it became necessary on occasion for the college to obtain a mortmain licence, several examples of which are preserved in the college archives. They are visually impressive documents, comprising parchment charters illuminated with pen-and-ink portraits of the ruler of the day, and bearing the ‘great seal’ of England on silken cords. Emmanuel was granted licences in the reigns of James I and VI, Charles II and George I, and in the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. This charter (pictured), issued in July 1654 and written in English rather than the Latin used before and after the Commonwealth, permitted the college to purchase land worth £500 a year. Traditionally, royal great seals had depicted the monarch enthroned on one side, and on horseback on the other, but Cromwell chose a new design symbolising the Protectorate. His seal displayed a House of Commons assembly on the obverse and a representation of England, Ireland and the Channel Islands on the reverse (Scotland was decapitated, as the Lord Protector used a different seal north of the border). Cromwell had personal links with Emmanuel, as two of his sons-in-law, Charles Fleetwood and John Claypole, had studied here, and his youngest son, Henry, was admitted in 1644. Although he did not graduate BA, Henry received an MA in 1654, when he became MP for Cambridge University.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist