Blog

30 October 2024

G is for … Gillick

The name of Royal Academician Ernest Gillick may not be well-known beyond the art world, but resident members of Emmanuel pass one of his sculptures nearly every day, and even the most library-averse student will occasionally encounter his two other college commissions. His most familiar work is the First World War memorial in the chapel cloister. This wall-mounted slab of Purbeck marble records the names of Emmanuel’s Fallen with minimal ornamentation, but the quality of the incised lettering, with its clever use of ligatures, is of the highest. Gillick’s first artwork for the college had been a bronze plaque, now installed above the main library staircase, depicting Evelyn Shuckburgh. A Fellow, librarian and historian of Emmanuel, Shuckburgh died in 1906. When Emmanuel’s Classics don, James Adam, died (at a relatively young age) the following year, the college initially contemplated asking Gillick to produce a companion plaque, but soon decided that a ‘symbolic design’, alluding to Classical antiquity, would be a more fitting memorial. Gillick consequently proposed a figure of Philosophy, standing before a bas-relief gilded panel depicting the nine Muses. The original design was not fully adopted, as neither the college nor Dr Adam’s widow, Adela, was entirely happy with it (she thought the principal figure looked ‘pinched and suffering’). Consequently, the sculpture was not completed until 1912, but it was worth waiting for, as it forms a striking and beautiful focal point in the main library reading room. ‘Sophy’ was originally to have held a circular marble plaque, but Gillick’s revised design substituted a laurel wreath. This gilded garland is detachable, resulting on occasion in its mysterious relocation to the figure’s head.

G is for … Graffiti

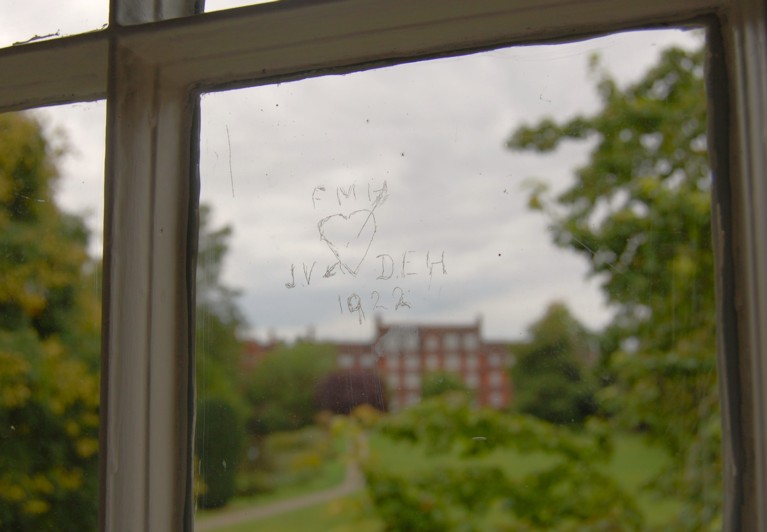

Stone-carving is best left to professionals like Gillick, although context or antiquity can certainly endow graffiti with a degree of interest. Several examples of this form of self-expression can be seen about the college. The inscription ‘R F 1670’, still faintly visible on the external east wall of Christopher Wren’s chapel, was made well before the building was completed. It was presumably carved by one of the masons, as no student with those initials was resident that year. A graffito in the chapel bell turret reads: ‘Thomas Holbech 1680’. We can safely assume that this was not the handiwork of the septuagenarian Master of Emmanuel, who died in autumn that year, but that of his great-nephew, who had matriculated in 1678. The smooth creamy-pink oolitic limestone of the chapel cloister has inevitably proved irresistible to graffiti ‘artists’ over the centuries, but fortunately their scrawls have usually proved easy to efface. A more erudite inscription can be attributed to Frederick Attenborough (father of Sir Richard, Sir David, and John). Frederick was at Emmanuel between 1915 and 1925, firstly as a student and then as Fellow. He was an Anglo-Saxon specialist, and for many years the name ‘Attenboro’, lightly carved in Old English runes, could be seen on the stonework near his rooms on B staircase. No trace of this inscription now remains, but fortunately a photograph of it survives. The arches above F and G staircase entries in Old Court have attracted several amateur chisellers over the centuries. As well as random incised letters, G’s arch displays a quadruped of some sort and a human face. Woodwork and glass also offer opportunities for graffitists. The back of a panel in the Welbourne Room bears the epigraph ‘Barkley 1647’, courtesy of William Barkley, admitted to Emmanuel in June of that year. A window pane in G5 displays the etching made in 1922 by the set’s occupants, John Vorley and Frederic Maxwell Harris. The mysterious lady presumably represented by the initials ‘D.E.H.’ has not been identified.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist