Blog

4 September 2024

E is for … Emmanuel

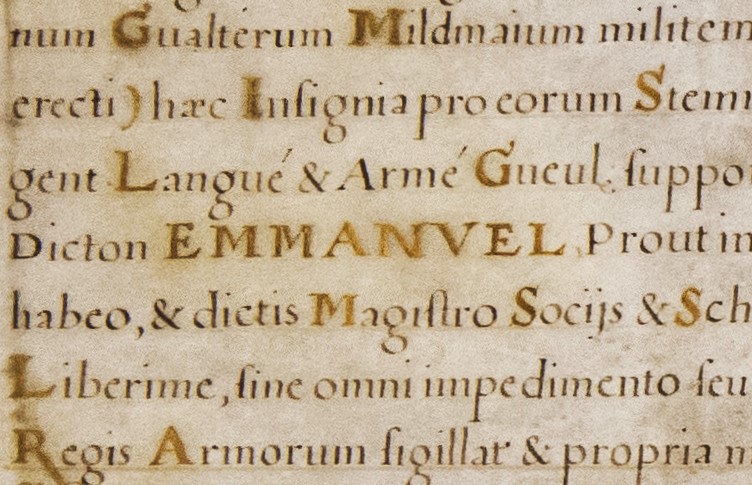

When Sir Walter Mildmay founded a new Cambridge college in 1584, it was a safe bet that its name would allude to the Christian faith, as his intention was to found a school of ‘prophets’, i.e. moderately Puritan clerics. The name Emmanuel is a transliteration of the Greek rendering of a Hebrew phrase meaning ‘the Lord [is] with us’, but should it have one ‘m’, or two? The most important early college documents, including the foundation charter, the grant of arms (pictured) and the statutes, all employ the spelling ‘Emmanuel’. The first Master, Laurence Chaderton, tended to save time and ink by writing only one ‘m’, but adding an abbreviation mark above it to denote the omitted letter. He was not alone in this habit. Conversely, the early nominations to college scholarships and fellowships, signed by Sir Walter although written by his clerk, invariably employ the longer variant ‘Emmanuell’, and this spelling is also commonly found in early college correspondence. Another popular rendering of the name was ‘Emanuel’ (without any abbreviation mark). This minimalist version was widely used for several centuries, and even as late as the mid-nineteenth century it can be found in Cambridge guidebooks and in the captions to printed engravings of the college. The closest transliteration of the original Hebrew is, in fact, ‘Immanuel’. Cotton Mather, an early alumnus of Harvard College (BA 1678), when reflecting on the large number of Emmanuel graduates who had emigrated to North America, wrote: ‘If New-England hath been in some respects Immanuel’s Land it is well; but this I am sure of, Immanuel College contributed more than a little to make it so..’. It is a striking thought that if Sir Walter Mildmay had favoured this spelling, we would now be using the pet-name ‘Imma’, not ‘Emma’!

E is for … Eltisley

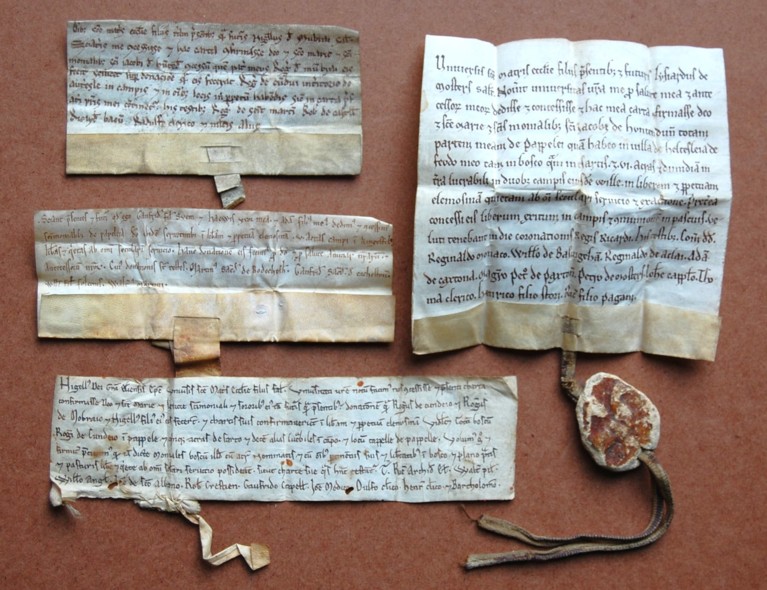

The small village of Eltisley lies eleven miles west of Cambridge. An estate there, known as the manor of Papley alias Papworth Everard, was purchased by Emmanuel College in 1593, for the substantial sum of £900. The manor comprised three messuages, two cottages, one dovecot, three gardens, three orchards, 200 acres of arable land, 40 acres of meadow, 30 acres of pasture, 30 acres of wood, and 200 acres of furze and heath. Although there is nothing especially remarkable about the property itself, it is of unique historical interest in one respect: the title deeds recording its changes of ownership date back more than eight and a half centuries. Indeed, they include the oldest documents held in the college archives. The first four deeds in the series are undated, as was quite usual at that time, but they contain references to well-known individuals such as Roger de Mowbray and ‘Nigel’ (Neil), Bishop of Ely, that date them to the third quarter of the twelfth century. Written at a time when parchment, ink and scribes were all expensive, the documents are admirably concise, with none of the verbosity that is such a baneful feature of later title deeds. The Christian names of the parties who feature in the deeds are predominantly Norman, rather than Anglo-Saxon, reflecting the wholesale replacement of the landowning class after 1066. Some of these names are still in use today, but others fell out of favour by the end of the Middle Ages: Folco, Ivo, Lisiard, Pagan, Gerbert. Complete oddities are Stor, Wimer and Helyd. The most unusual woman’s name found in the deeds is ‘Argencelina’. This rather heathen-sounding name (‘silver moon’?) was very rare even then, but it survived as ‘Argent’ in Cornwall. Although some of the earliest Eltisley deeds have lost their wax seals, they are otherwise in almost perfect condition, despite their great antiquity.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist