Blog

4 September 2024

For all their importance, cooking and kitchens are illustrated rarely and almost incidentally in the College’s collection of illustrated books. The few pictures to be found represent a very different world from the idea of the modern kitchen, whether that is the sleekly gleaming idyll in the interior design magazines or the worn and messy reality in the home.

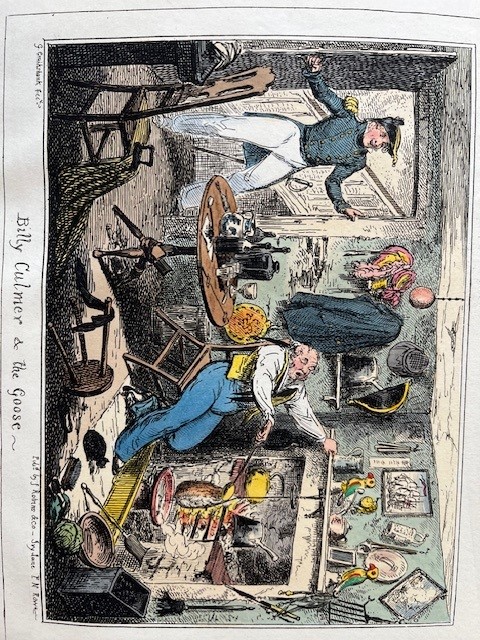

How most people cooked happens to be depicted incidentally in a seriocomic book about naval life entitled Greenwich Hospital (1826), which has the lengthy sub-title ‘A Series of Sketches, Descriptive of the Life of a Man-of-War’s Man, by an Old Sailor’. One of the ‘sketches’ is the tale of a sailor who is reluctant to board his ship when she sails because he is busy roasting a plump goose.

Greenwich Hospital: A Series of Naval Sketches, Illustrated by George Cruikshank (1826)

Greenwich Hospital: A Series of Naval Sketches, Illustrated by George Cruikshank (1826)

The goose is shown suspended by a wire from a rotating wheel in front of the fire in a cluttered living room. The coal is banked up in a kind of range, fronted by a grille. A large saucepan is perched steeply on top of the coals. A large kettle is on the side. The sailor is basting the fowl over a bowl below to catch the fat. A black cat is gazing intently at the roasting meat. With variations, cooking over a domestic hearth like this would be the norm in many households.

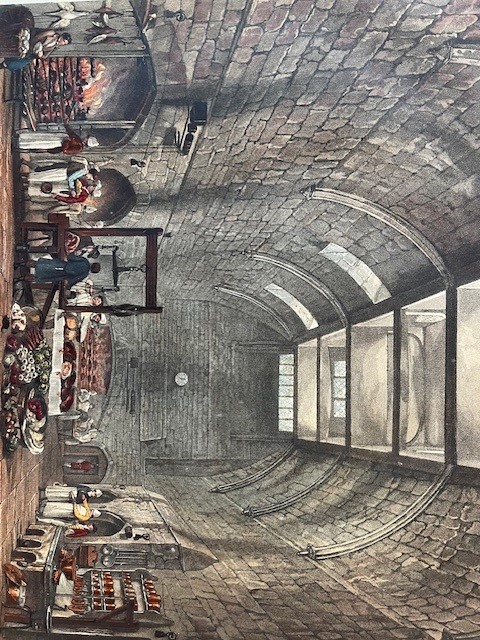

Other illustrations of kitchens and cooking tend to occur in books illustrating grand and historic buildings. Such pictures are found rather occasionally and are perhaps included for a kind of negatively picturesque value. These kitchens of large households are spaces of a smoky grandeur that complements depictions of the interiors and exteriors of castles and colleges that figure on the other pages of illustrated books. In the deluxe illustrated volumes for both Oxford and Cambridge that the publishing entrepreneur, Rudolph Ackermann, produced in the early nineteenth century, there is only room for pictures of the kitchens of the largest college in each university, probably because these cavernous spaces had a picturesque dimension absent from smaller college kitchens. The picture of the kitchen at Christ Church, Oxford, certainly suggests how the fires, heat and smoke of kitchens had traditionally been associated with hell.

Kitchen, Christ Church, in R. Ackermann, History of the University of Oxford (1814)

Kitchen, Christ Church, in R. Ackermann, History of the University of Oxford (1814)

Clouds of smoke are issuing from an enormous open fire, before which numerous fowls are being roasted on a grille, with a pan below for the fat. There appears to be nowhere for the smoke and condensation to escape, apart from through the large open shutters, which presumably needed to be open in all weathers. In the foreground a man prepares yet more fowl for roasting at one table and a woman prepares a small mountain of green vegetables at another. The walls appear to be predictably grimed with smoke and soot from generations of cooking in the space.

The illustration of the kitchen at Trinity College, Cambridge, shows a similarly gloomy and cavernous space, although the inclusion in the picture of the kitchen roof with its lantern might suggest that there was some provision for the escape of smoke and smell through that.

Kitchen, Trinity College, in R. Ackermann, History of the University of Cambridge (1815)

Kitchen, Trinity College, in R. Ackermann, History of the University of Cambridge (1815)

To the left, before a raging fire, some staff are working in what would be scorching heat. There appears to be a system of pulleys over the hearth in order to rotate the roasting meat on spits. A woman takes a break with a dog; a maid sweeps up. A man seems to be preparing a large fish. At an ‘island’ others may be preparing pastry; three headless fowl droop over the edge. Vegetables lie unceremoniously on the floor.

The ‘Ancient Kitchen’ at Windsor Castle shows another distinctly grimy and cavernous space, although it is generously top-lit with windows.

‘Ancient Kitchen’, Windsor Castle, in W. H. Pyne, The History of the Royal Residences (1819)

‘Ancient Kitchen’, Windsor Castle, in W. H. Pyne, The History of the Royal Residences (1819)

To the left, meat is being roasted before a huge fire on spits worked by pulleys above, while more is being roasted at another hearth in the far wall. There is a weighing machine and a table groaning with meat in the centre. People prepare food at a further table. Game is being hung on the wall, and vegetables lie in a heap on the floor.

By contrast, the kitchen at St James’s Palace presents a more wholesome regime.

Kitchen, St James’s Palace, in W. H. Pyne, The History of the Royal Residences (1819)

Kitchen, St James’s Palace, in W. H. Pyne, The History of the Royal Residences (1819)

There is much more light, even if the walls do bear the stains of smoke and steam.

Things seem a lot cleaner, including the staff, who are crisply attired for their work. The surfaces and fittings are uncluttered and orderly, designed for the space with drawers. Serried rows of copper pans gleam on shelves and utensils hang neatly in their places. Meat is still being roasted in front of a roaring fire in the hearth, and it looks like a spit is being loaded in front of the window. But this kitchen does look rather more like the later nineteenth-century kitchens that readers will have seen in tours of country houses. Still to happen are all the innovations in ovens and other cooking appliances, not to mention societal changes, that have helped put the kitchen at the core of modern homes, even if that kitchen may not always look quite like the interior design magazines.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books