Blog

31 July 2024

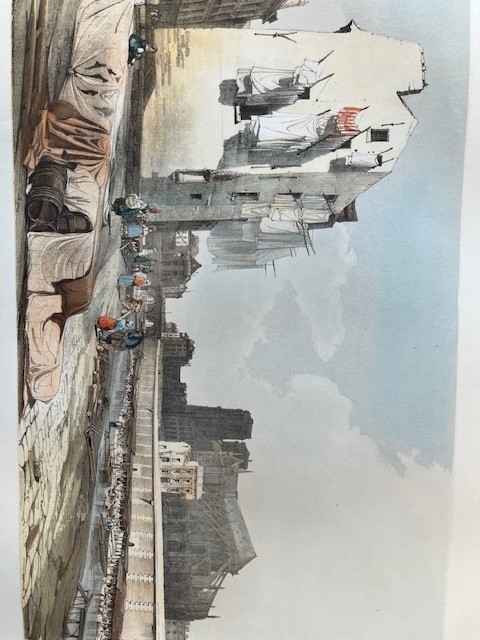

J. C. Nattes, Versailles, Paris, and St Denis (1810), ‘Bridge of the Hôtel Dieu, with the Church of Notre Dame’

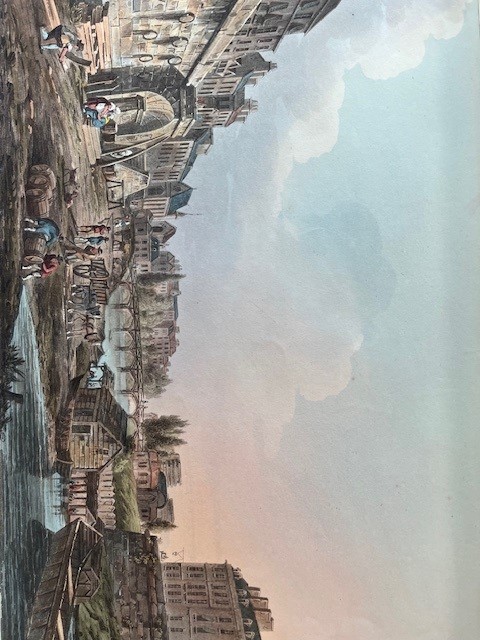

This year’s Olympic Games have put the spotlight of world attention on the iconic cityscapes of Paris. British fascination with the French capital is already attested by the early nineteenth-century illustrated books in Emmanuel’s collection. One of the interests in these books now is that the Paris they record – and the perceptions of it – are not the city as it would be re-fashioned later in the century and is broadly still. There is, of course, no Eiffel Tower (1889) and no Sacré-Coeur (1876-91). Even the Arc de Triomphe, though begun in 1806, took 30 years to build. Construction of the great boulevards of the Second Empire (1852-70), which flattened large areas of the old Paris, were still in the future. So too were the new green spaces – Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes etc – which Napoleon III ordered to be made at the four compass points, because he wanted Parisians to have the green spaces that he remembered from his exile in London, especially Hyde Park. The Emperor gave orders that Paris be beautified, and it was.

Illustrations of Paris produced rather earlier in this country therefore have a different focus. Some dwell on customs and characteristics, on street life. Some are interested in recording the jumbled and quaint in ancient buildings and streetscapes. As so often, the focus is on the picturesque, and books that are concerned with ‘views’ of the significant buildings of the old Paris will present them with some picturesquely decayed and shabby aspects.

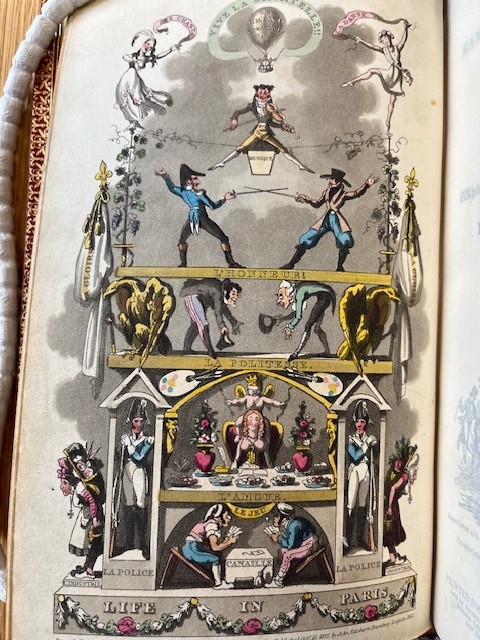

The frontispiece to David Carey’s Life in Paris (1828), with illustrations by George Cruickshank, is a revealing cartoon of British perceptions of the French and hence of their capital.

D. Carey, Life in Paris (1822). Frontispiece

At the top is a balloon because ‘their light ascending spirits are appropriately figured by a Balloon'. There are song, music and dancing, to which the French are ‘very partial’, and then a duel, under the heading of ‘Honour’, about which the French are reported to be very touchy. Glory is inscribed on a flag because the French think no one possesses it except them. Politeness is signalled by two obsequious figures. Below is Love, with a blindfolded Cupid behind an amply endowed barmaid in a café. Beneath are some gamblers because ‘the vice of gambling pervades all classes in France’. Two French women bear up industry, which the male figures neglect.

The sub-title to Carey’s book summons up a kind of British engagement with ‘abroad’ that is perhaps still alive in mass tourism: it comprises ‘the Rambles, Sprees, and Amours of Dick Wildfire … and his Bang-Up Companions … with the Whimsical Adventures of the Halibut Family, including Sketches of … Eccentric Characters in the French Metropolis’. The sub-title of William Combe’s Dr Syntax in Paris, ‘or A Tour in Search of the Grotesque’ (1820) indicates that this is a spin-off from the hugely popular satires that spoofed the contemporary fad for the picturesque, but here the gullible doctor is a tourist in Paris, where Mrs Syntax has a fit of the vapours while visiting the tourist attraction of the catacombs.

W. Combe, Dr Syntax in Paris (1820), ‘Dr Syntax visits the Catacombs’

For armchair travellers, or those who wanted a reminder of their time in Paris, there were books with plates of exceptional accomplishment and beauty. The Versailles, Paris and St Denis (1810) of John Claude Nattes, a French topographical draughtsman and water colour artist based in London until 1822, gives many insights into the topography and social history of Paris at the start of the nineteenth century.

Nattes is especially fond of views from under the bridges of Paris, allowing close-ups on ordinary activities from out of the ordinary perspectives.

Nattes, Versailles, Paris, ‘From under the arch of St Michel’s bridge’

Nattes, Versailles, Paris, ‘The washing place belonging to the Hospital of L’Hôtel Dieu’

This is a very much less spruce, polished and finished Paris than that of modern expectation and all the more interesting for that.

Nattes, Versailles, Paris, ‘From one of the arches of Notre Dame’

Nattes, Versailles, Paris, ‘View drawn from under the Arch of Givry’

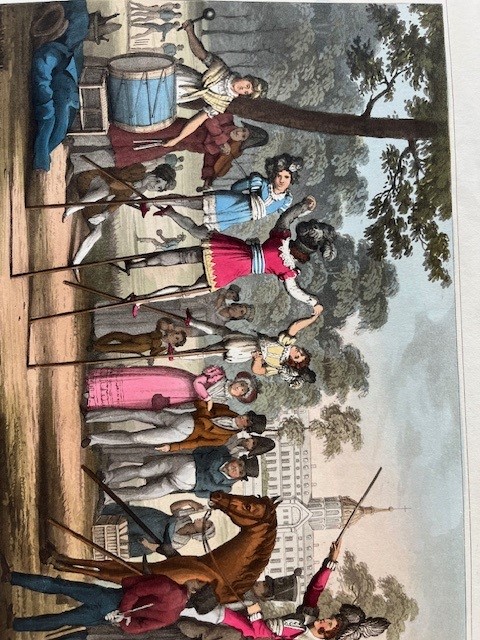

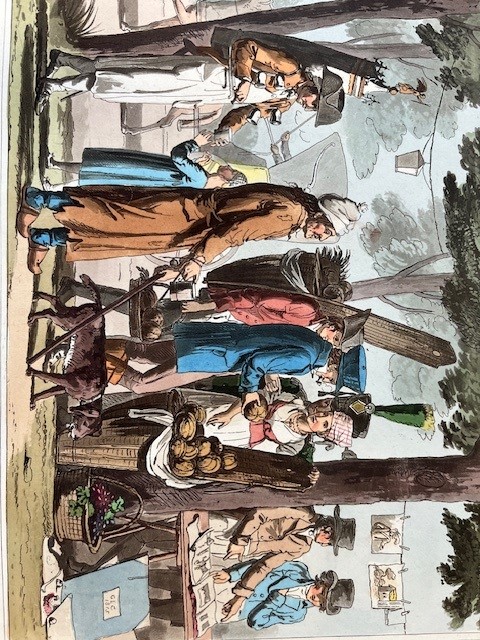

Other publications present the customs and costumes to be seen on Paris streets.

A Tour through Paris (1828) does this in aquatints with particularly skilful and vibrant colouring.

Sams, A Tour through Paris (1828), ‘Dancers on Stilts in the Champs-Elysées’

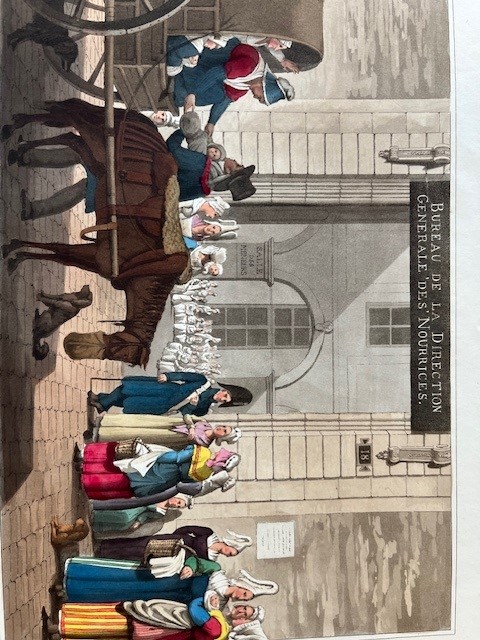

Sams, A Tour through Paris, ‘The Office of Nurses’

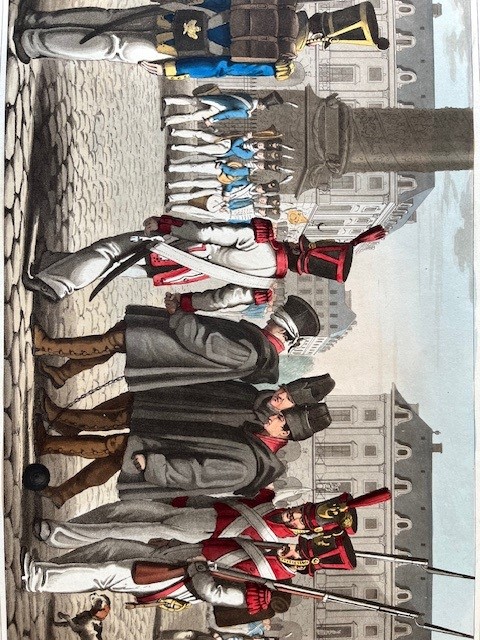

One plate features the historic institution of the Office of Nurses (i.e. wet nurses). The English commentary tuts that ‘this is a market for human milk … where so many women are seen flocking with full breasts, in order to supply children to whom they are strangers’. What was founded by Louis XIV as a philanthropic project has been turned into a profitable business controlled by men. Nurses sleep in one large dormitory between the cradles of the two babies that each nurse sustains at any one time. A plate of itinerants on the boulevards includes, on the left, a dealer in tisane with his stove on his back, and a blind man with his dog. Another plate shows the ceremony in which disgraced soldiers are cashiered in the Place Vendôme.

Sams, A Tour through Paris, ‘Itinerants on the Boulevards’

Sams, A Tour through Paris, ‘Military Degradation in the Place Vendôme’

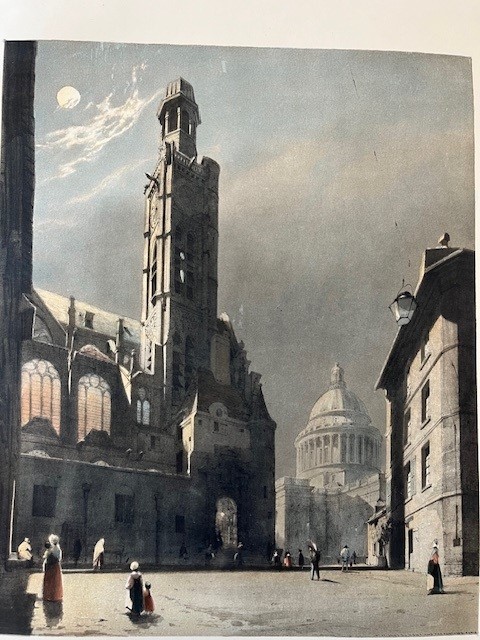

By 1839, in his Picturesque Architecture in Paris, Thomas Shotter Boys (1803-74) accomplishes an early triumph of lithography technique, achieving cool, transparent, graduated tints, subtle in colouring. King Louis Philippe sent Boys a ring in token of his admiration for this book.

Shotter Boys, Picturesque Architecture (1839), ‘Notre Dame’

Shotter Boys, Picturesque Architecture (1839), ‘Notre Dame’

Shotter Boys, Picturesque Architecture, ‘Hôtel de Cluny’

The image of Notre Dame is especially interesting in setting the cathedral in the same picture with buildings festooned with drying washing and with the banks of the Seine cluttered with everyday trade and activity. The image of the Hôtel de Cluny notes that it has ‘been recently bought by the French Government to preserve its remains as a national monument’.

Similarly subtle in colouring, the image of the Rue Notre Dame is a record of streets in the old Paris, long replaced (note the boots for sale outside a shop).

Shotter Boys, Picturesque Architecture, ‘Rue Notre Dame’

Shotter Boys, Picturesque Architecture, ‘St Etienne du Mont, with the Pantheon’

The plate of the Church of St Etienne du Mont and the Pantheon by moonlight is a rare attempt at a nocturnal cityscape, which inevitably seems to anticipate the later characterization of Paris as the ‘City of Light’.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books