Blog

26 March 2024

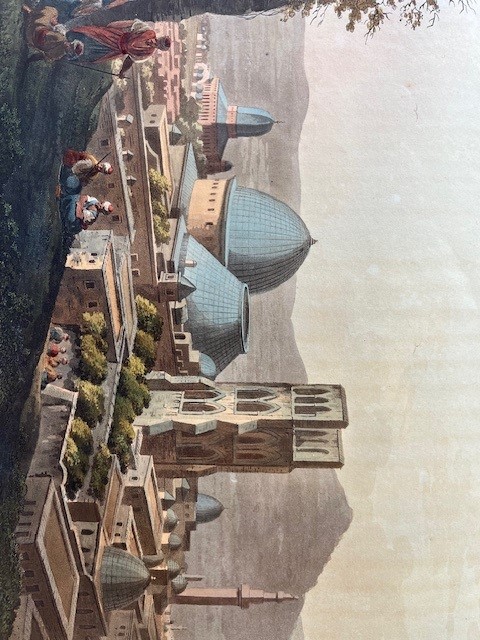

Mayer, ‘Views’: Jerusalem, with the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

In Holy Week, thoughts turn to the Holy Land, and never more so than this year. Emmanuel’s collection of illustrated travel books from the late eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries contain only limited images of the area, which was just becoming an object of curiosity to more intrepid spirits, interested in travelling wider than Europe in search of the picturesque. The splendid exception is Views in Egypt, Palestine, and other parts of the Ottoman Empire (1804) by Luigi Mayer (1755-1803). Italian-born, of German ancestry, Mayer was commissioned by Sir Robert Ainslie Bt, British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire (1776-1792), to record landmarks and landscapes throughout the Ottoman possessions. (Ainslie presented Mayer’s original paintings to the British Museum).

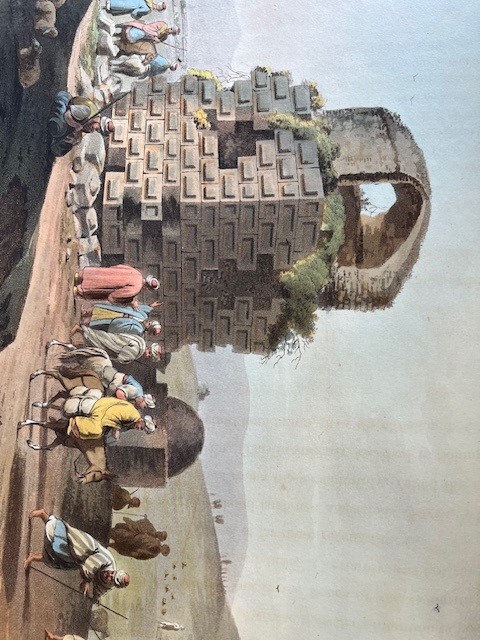

As the nineteenth century wore on, advances in communications and much improved opportunities for tourism resulted in an enormous increase in the numbers visiting the Holy Land. A special interest of Mayer’s ‘views’ is that they record some of the sites famous from Biblical accounts as they still were before this onslaught. Mayer presents the Holy Places in a picturesque dilapidation, as they had apparently remained during the long centuries of the Ottoman Empire’s decline.

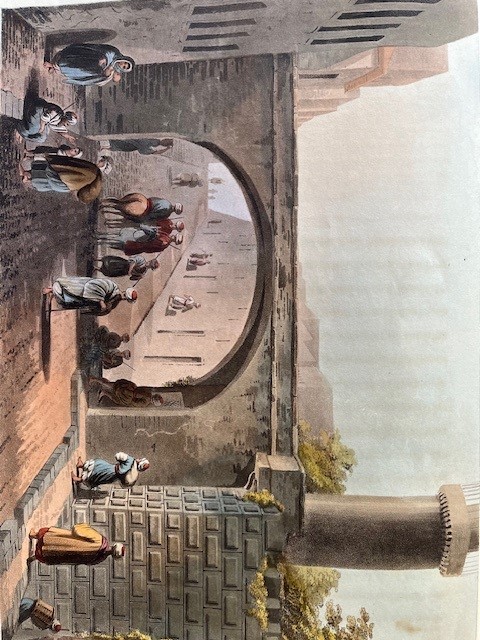

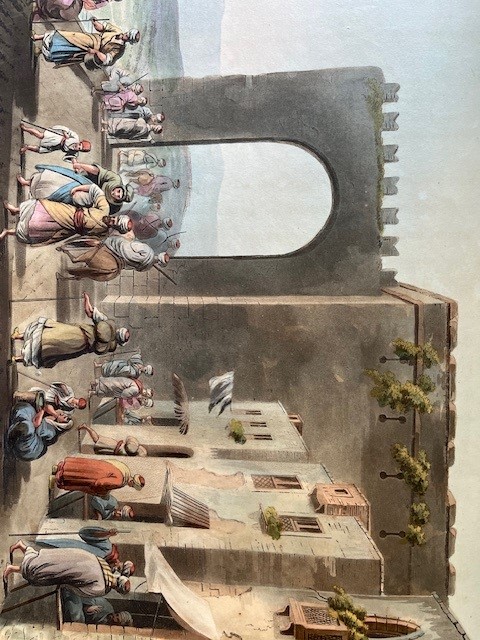

Mayer’s street scenes in Jerusalem can thus appeal to the age’s much wider taste for the melancholy inspired by the prospect of ruins, as well as recording the current state of places mentioned in the Bible’s narrative of events in Holy Week.

Pillar to which was affixed the sentence passed on Our Saviour

Remains of a Tower on Mount Zion

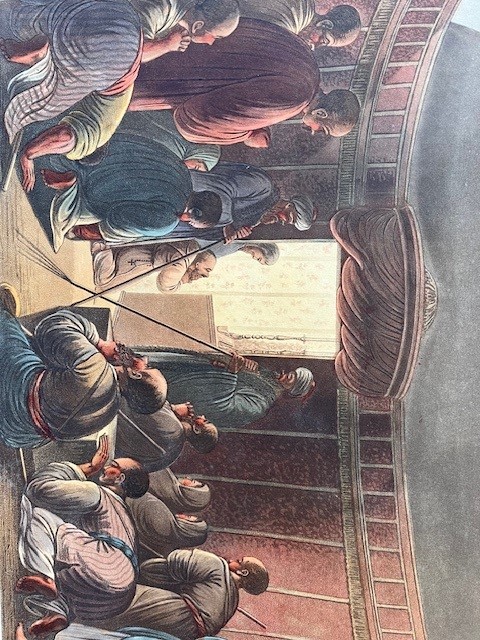

For Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem the most important site has always been the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built over the site of Christ’s crucifixion on Mount Calvary. Inside the Church, pilgrims visited the site of the cross and the sepulchre, as well as the places where, it was believed, Christ was nailed to the cross and where his body was later anointed by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus. Mayer’s views catch the gloom of these interiors, lit by candles.

Entrance of the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre

Tomb of Joseph of Arimathea

This is also so of the reputed sepulchre of the Virgin Mary near the Garden of Gethsemane, over which a church had been erected by St Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine. Pilgrims descended into the subterranean church to where the Virgin’s tomb stood in a chapel hewn out of the rock. Her tomb was venerated by local Muslims, who helped defray the cost of the eighteen lamps kept constantly burning in front of the Virgin’s tomb. Here, as in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, only the thresholds of the most sacred shrines are depicted.

Tomb of the Virgin Mary

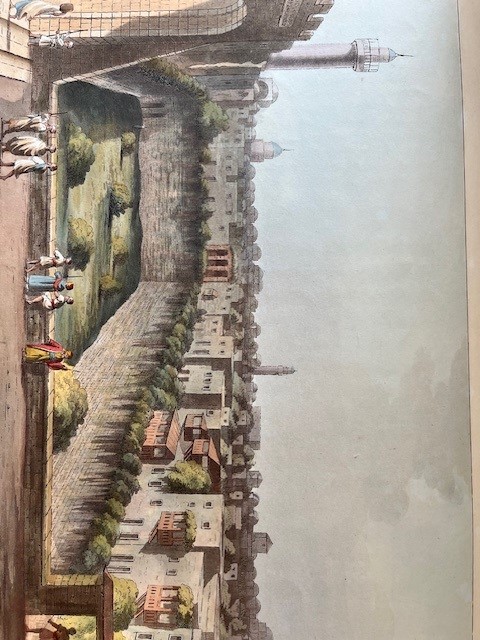

The Pool of Bethesda, Jerusalem

Much less frequented was the Pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem, where Jesus bid a paralysed man ‘Rise, take up thy bed and walk’ and so he did (John 5: 8-9). At what was believed to be the site in Mayer’s day any springs of water had dried up and the site was overgrown.

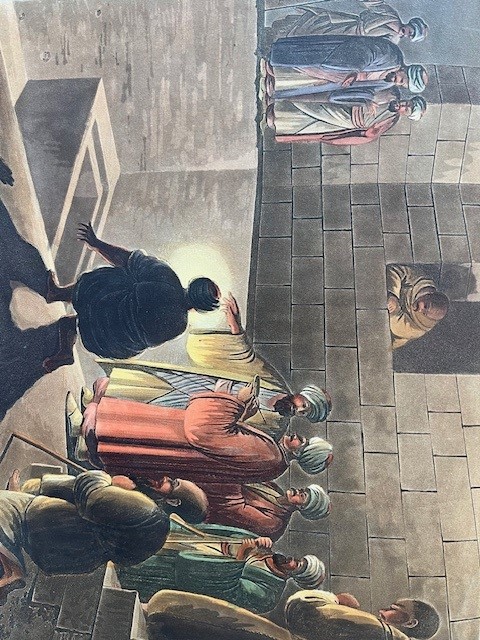

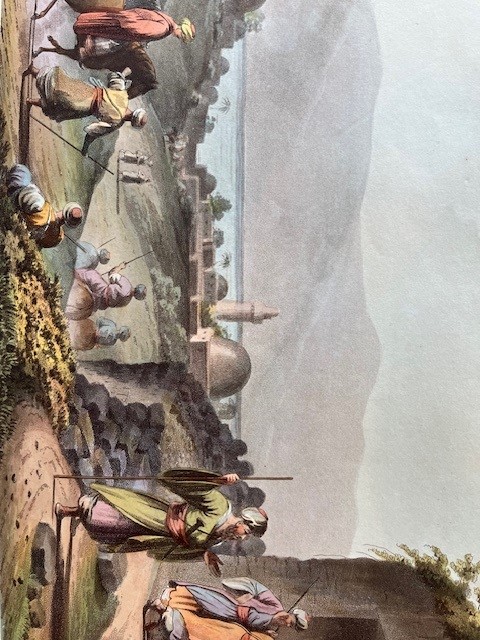

At Bethany was the home of the sisters Martha and Mary, whose brother Lazarus Christ raised from the dead after four days (John 11: 1-45), a miracle that prefigured his own resurrection. Mayer also illustrates some subterranean tombs at Bethany, by implication the site of the miracle.

The Village of Bethany and the Dead Sea

Sepulchral Chamber near Bethany

Also illustrated are scenes at Bethlehem, where a church had been built over the supposed site of Jesus’ birth. There was a subterranean chapel of the Nativity, with a further chamber exhibiting the manger, along with a handy shelf upon which the Three Wise Men were believed to have deposited their gifts. A nearby cave contained a vault ‘where they say’ were buried the Holy Innocents, the children murdered by Herod. Also to be seen was the grotto ‘in which they report’ St Jerome remained for fifty years – rather understandably since he twice translated the Bible into Latin there.

Principal Street of Bethlehem

Subterranean Church of Bethlehem

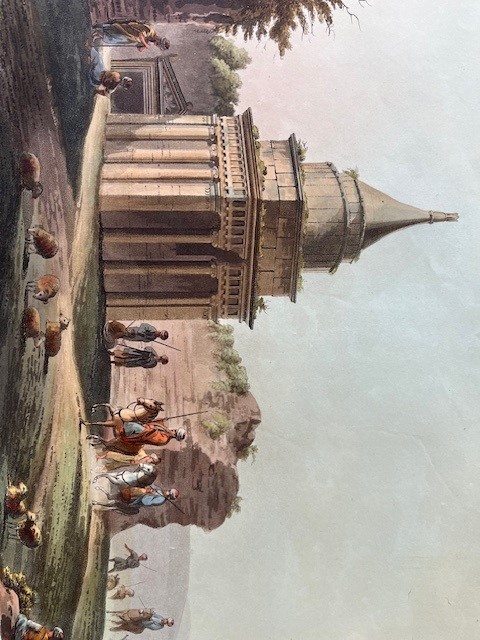

As Mayer travels around sketching and painting, he also records ruins, reputedly from Old Testament times, in states of picturesque decay, such as the tomb that Absolom had reportedly built for himself, or the supposed tomb of Rachel, the wife of Jacob, although in his accompanying commentary Mayer sniffs that she was certainly never buried in a building so relatively modern.

Sepulchre of Absolom

Sepulchre of Rachel

In Mayer’s record of the picturesque, stones are tumbled and vegetation sprouts from ruins. Outside, vistas recede, while in dim interiors gleam spots of light in a religious glow. It is an intriguing snapshot through western eyes of places familiar from the Old and New Testaments at the end of the eighteenth century.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books