Blog

28 February 2024

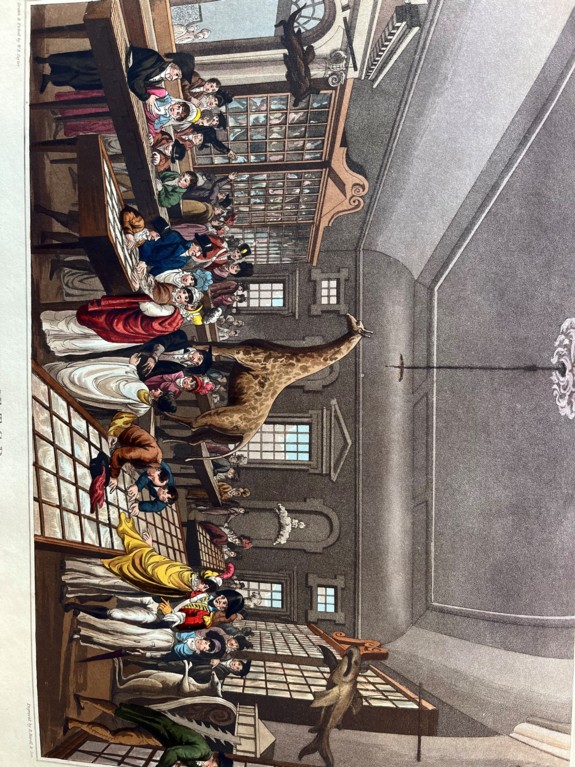

A curious public inspects the curiosities in the museum at Trinity College Dublin; W. B. Taylor, History of the University of Dublin (1819)

Emma Connects has just passed its one hundredth edition since it was created in order to reach out to Emmanuel members during the isolation, and perhaps loneliness, of the first lockdown. Soon it will be four years since the first Rare Book blog appeared in April 2020, describing a book published in 1665, the year of the Great Plague, that recommended ‘It is advisable that all needless Concourses of People be prohibited …’ This is the sixty-fourth of these Rare Book blogs since that beginning, although they have barely scratched the surface of the College’s rare book collections. The positive outcome of what began prompted by adversity is that the interest and beauty of Emmanuel’s illustrated books – many now quite fragile to handle – can be appreciated by a much wider readership than ever before.

What never ceases to impress is the sheer energy of curiosity represented by those who created these books and those who collected them. Two books written by intrepid women make this point. The title page of Narrative of a Residence at Tripoli in Africa (1816) gives the author as Richard Tully, but the introduction at once acknowledges that the memoir is that of his sister, recalling experiences from thirty years earlier, when Tully was the British Consul at Tripoli, and his young daughters grew up speaking Arabic and on terms of close friendship with the family of the Bashaw, or ruler, of Tripoli.

Miss Tully, Narrative of a Residence at Tripoli: Officers of the Grand Seraglio Regaling

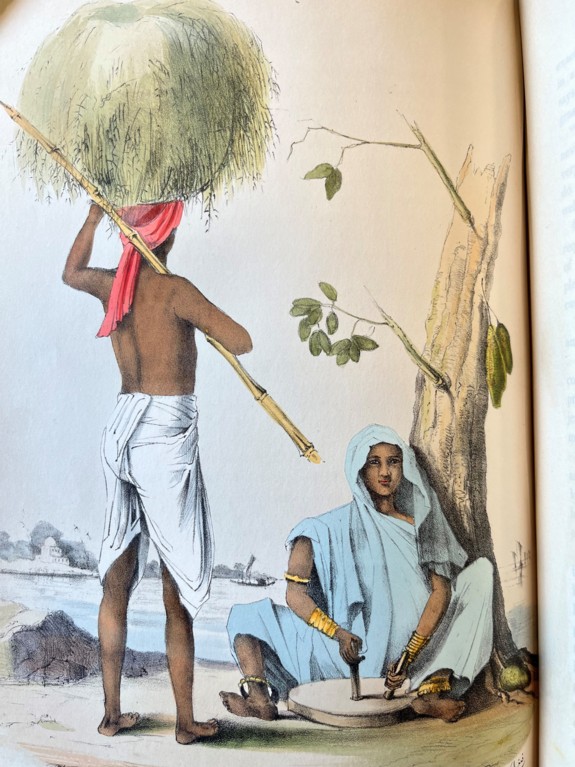

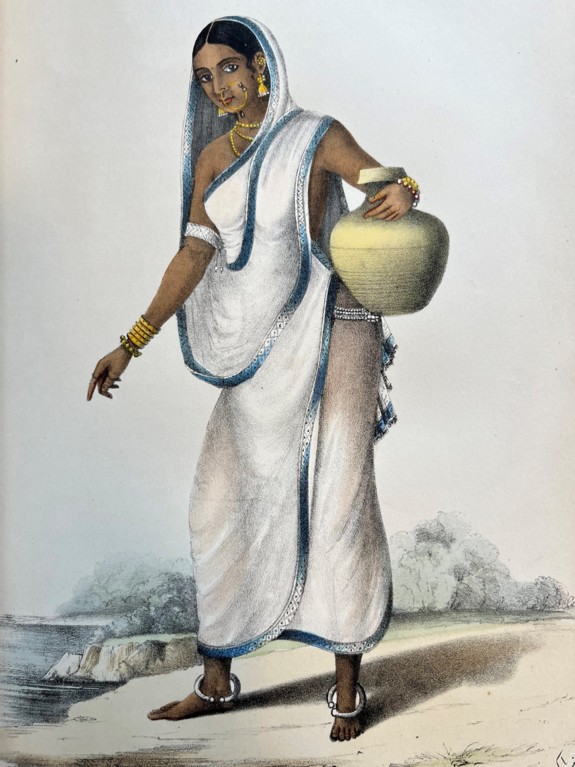

Fanny Parks published extensive journals of her time and travels in India as the wife of a British official in Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, during four-and-twenty years in the East (1850), but in a self-effacing gesture her name appears on the otherwise-English title page only in Urdu script. She is a sympathetic admirer of Indian culture and customs, sometimes allowing herself to criticize such English ways as the legal position of married women.

Fanny Parks, Wanderings of a Pilgrim: Grass-Cutter and Gram-Grinder; A Bengali Woman

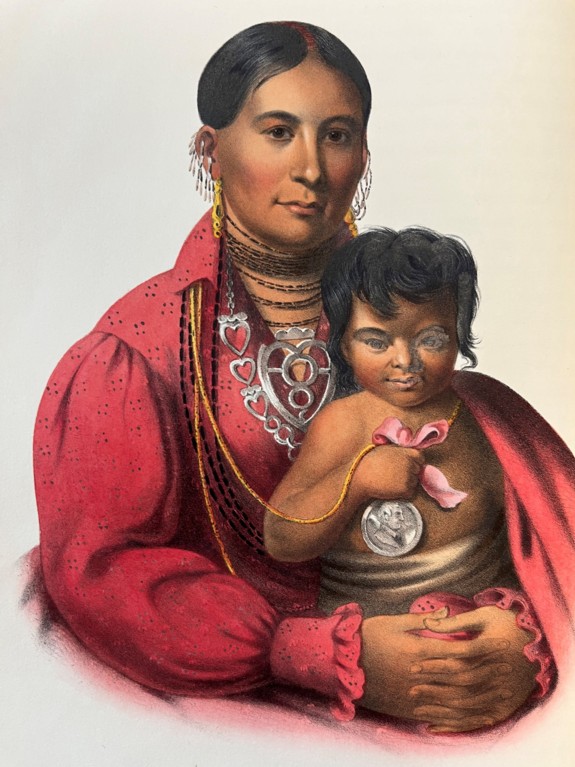

Thomas McKenney and James Hall’s, History of the Indian Tribes of North America (Philadelphia, 1848-50) was based on portraits commissioned by McKenney of Native Americans who came to Washington to negotiate treaties. McKenney was Superintendent of Indian Trade and hoped to preserve ‘whatever of the aboriginal man can be rescued from the destruction which awaits his race’. With the advantage of hindsight, it is hard not to see that doomed dignity in the solemn composure of these portraits.

McKenney and Hall, History of the Indian Tribes: An Osage Woman; A Chippewey Chief

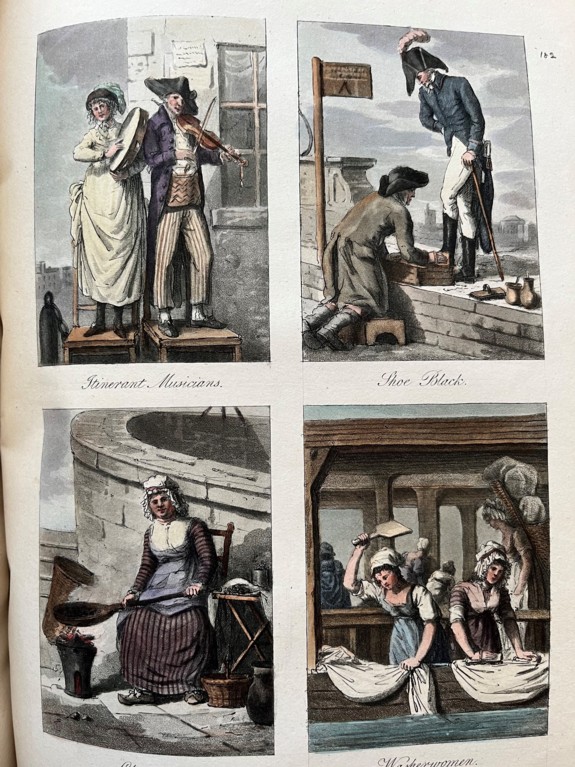

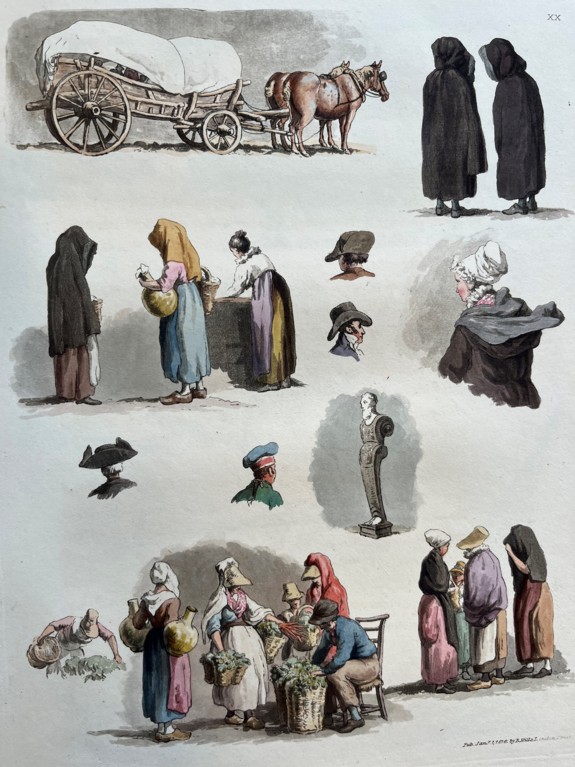

But the customs and costumes of countries much closer to home might prompt just as much curiosity. Both A Sporting Tour through France (1805) by Colonel Thornton and Sketches in Flanders and Holland (1816) by Robert Hills find space, in books largely devoted to views of landscape and architecture, to include studies of figures in local costume in the Low Countries or engaged in their trades on the streets of Paris.

Thornton, A Sporting Tour: (clockwise) Itinerant Musicians, Shoe Black, Washerwomen, Hot Chestnut Seller

Hills, Sketches in Flanders

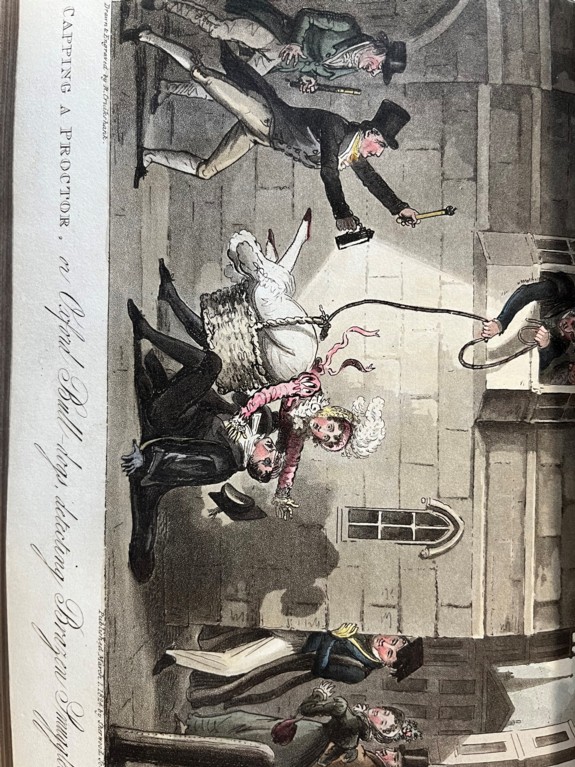

There are also a wealth of illustrated books presenting a wry, serio-comic take on the life of the well-to-do, which often includes a spell at university (more usually Oxford than Cambridge), where comic misdemeanours can be illustrated, as in this plate drawn and engraved by Robert Cruikshank, showing an undergraduate hoisting a ‘fair nun of St Clement’s’ up to his room in a basket, only to succeed in dropping her on to a passing proctor. (He is sent down).

William Westmacott, English Spy: ‘Oxford Bull-Dogs detecting brazen smuggling’

W. Sams, The Tournament

Such illustrations perhaps appeal both to the curiosity of those who haven’t been to college and to the nostalgia of those who have. A new nostalgia is also stirring for a re-imagined version of a ‘Gothick’ medieval past where valiant knights rescue swooning damsels from unwelcome oppressors, as in the illustrations to a truly dreadful book-length poem, The Tournament, or, Days of Chivalry (1823).

Another spur to curiosity for illustrated books probably lay in how so many of the early readers of such illustrated books – both men and women – will themselves have been taught to draw and paint as part of a polite education. Many of the flower books in the College’s collection present both a coloured and uncoloured version of each flower, with the latter available to be coloured by the owner.

Miss J. Smith, Studies of Flowers from Nature: ‘Dahlia’ coloured and uncoloured versions

Such books are directed at purchasers who may well have had a trained eye for painting in water colours every sort of subject from flora and fauna, but especially flowers and birds.

Thomas Martyn, Aranei; or A Natural History of Spiders (1793), frontispiece

Edouard Travies, Les Oiseaux: scenes varies, etudes a l’aquarelle (1857): Bird of paradise

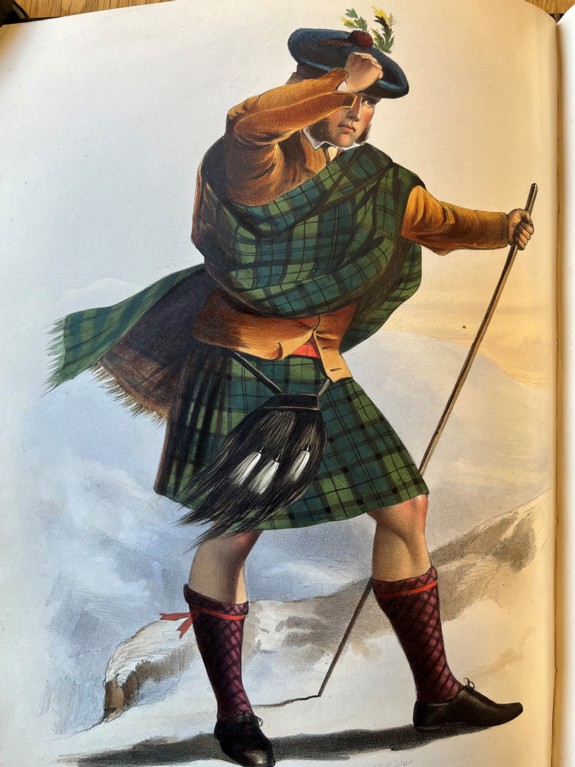

Curiosity goes along with innovation in the superb illustrations of clansmen in their tartans in McIan’s The Clans of the Scottish Highlands, 2 vols. (1845-57).

R.R. McIan, Clans of the Scottish Highlands: ‘Sutherland’, and Frontispiece to Volume 2

For although the pictures of clansmen are hand-coloured lithographs, the two magnificent heraldic title pages are successful early examples of colour printing. ‘Printed in colors’ (sic) it says modestly in very small type at the foot of the page, but this is part of a transition to a whole new future in the production of illustrated books.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books