Blog

31 January 2024

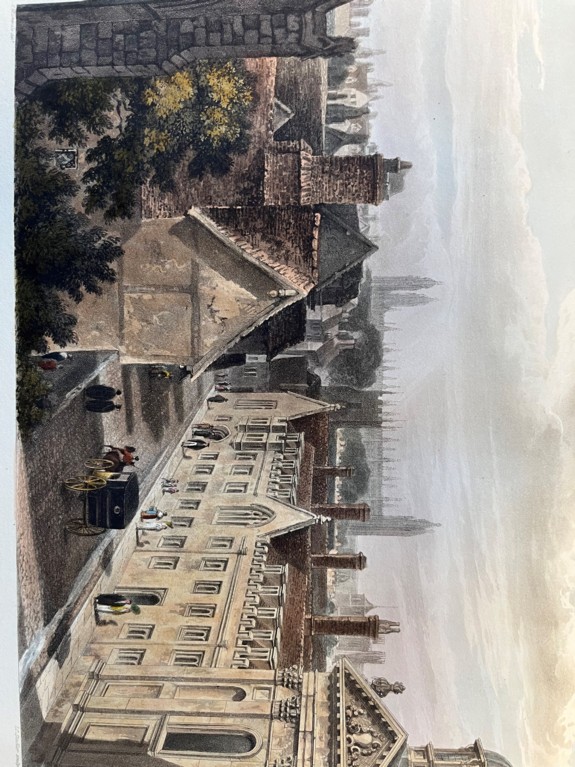

R. Ackermann, History of the University of Cambridge (1815), ‘Pembroke Hall etc., from a window at Peterhouse’

Visitors viewing the richly illustrated books in Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection often wonder why such a flowering of hand-coloured books and prints occurs in Britain at this time, roughly the first three decades of the nineteenth century. Breakthroughs in the technical processes of aquatint and lithography are the key contributing factor. But another major influence was the entrepreneurial genius of Rudolph Ackermann (1764-1834), a passionately Anglophile German immigrant publisher. His publication of a series of lavishly illustrated histories of Oxford, of Cambridge, and of historic public schools, were shrewdly pitched to appeal to an elite market among their alumni, but they were also so beautiful that they continue to shape perceptions of those places.

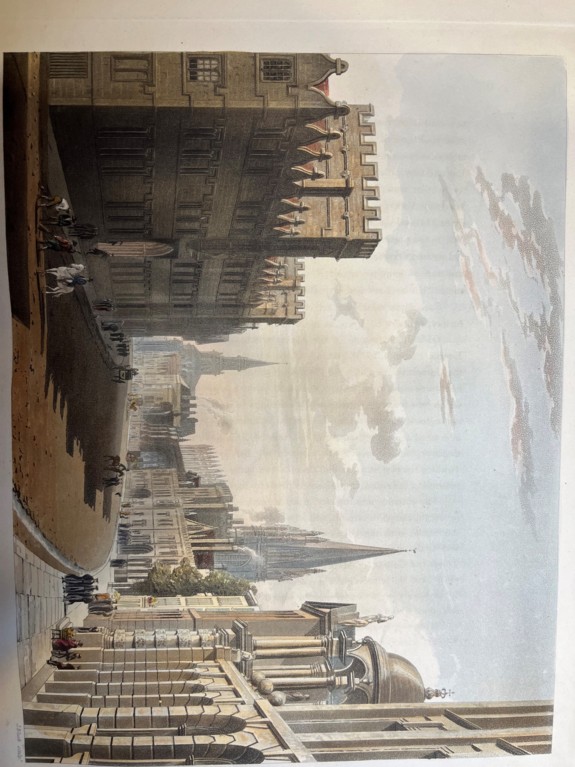

R. Ackermann, History of the University of Oxford (1814), ‘View of Oxford, taken from New College Tower’

‘Oxford, High Street, Looking West’

After an early career as a coach-builder and designer in Germany, Ackermann arrived in London in 1787, initially to pursue the same business. But by 1797 Ackermann had opened ‘The Repository of Arts’, a shop in the Strand famous in its day for pictures, prints, illustrated books, as well as paper, paints and artists’ materials aimed at the burgeoning market of amateur artists. These elegant premises became a fashionable haunt for those who wanted to be seen to have sophisticated tastes, not only in art but in fashion and décor. Tea and lectures were available. From 1809 Ackerman published a monthly magazine, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics, full of articles and illustrations of fashion, furniture and social news. During its twenty-year run, The Repository published over 1400 hand-coloured plates. The fashion plates, sometimes with dress-making patterns, were immensely influential on women readers.

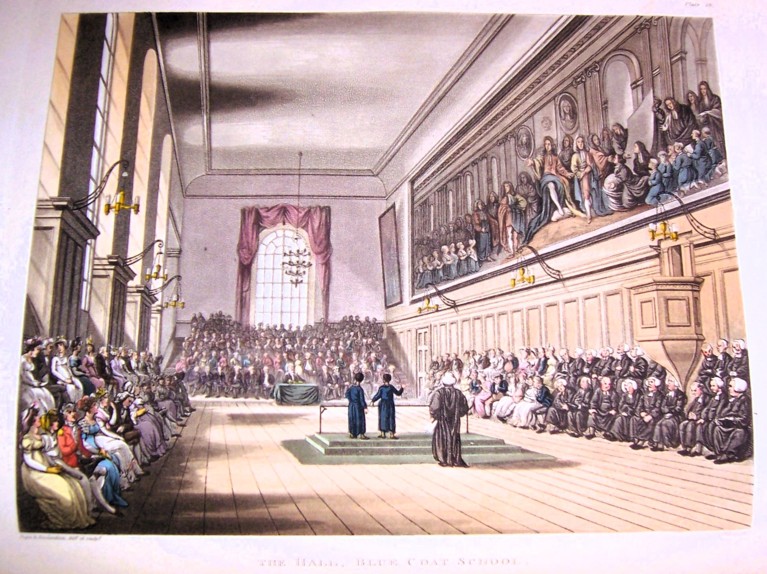

From publishing prints there was a logic in Ackermann’s move into publishing illustrated books, such as his sumptuous three-volume Microcosm of London (1808-1810), containing 104 hand-coloured aquatints, with outside and inside scenes of London landmarks and institutions. The plates are often revealing of current social practices, such as visitors to an exhibition of watercolours, or a ‘speech day’ event at the Blue Coat School, where two scholars – known as ‘Grecians’ and destined for Oxford or Cambridge – were required to recite orations ‘in praise of this institution, one in Latin and the other in English’.

Microcosm of London (1808-1810), ‘Exhibition of the Society of Painters in Water Colour, Old Bond Street’

Microcosm, ‘The Great Hall, The Blue Coat School’

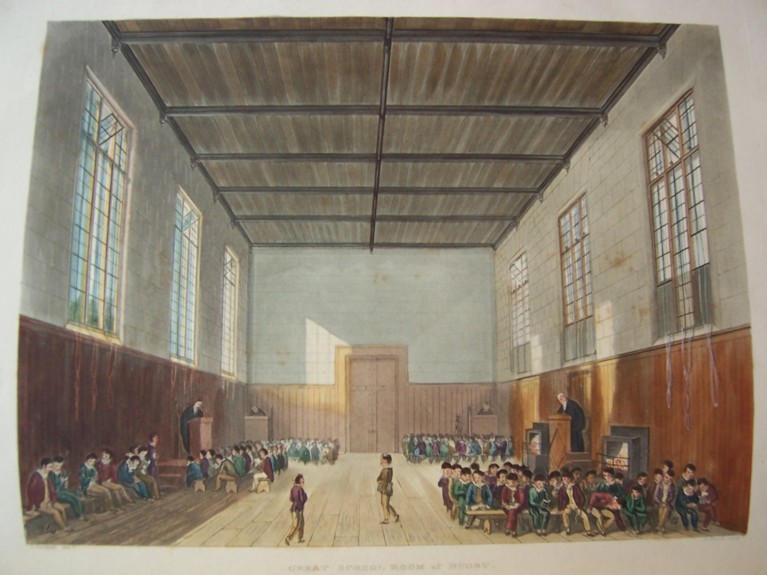

Like the Microcosm of London, Ackermann’s history of the public schools has a profusion of plates highlighting picturesque views of ancient buildings, so it is valuable that just one plate for each school actually provides a record of the educational process in these institutions, and a surprising one to modern eyes in terms of ‘class size’.

History of the Colleges of Winchester etc. (1816), ‘Eton College, School Hall’

‘The Merchant Taylors’ School Room’

In each of the schools, the plates show instruction of large groups of pupils by a number of teachers taking place within one very large, hall-like room. The competing noise must have been both a distraction and perhaps a training in concentration.

‘Harrow School Room’

History of Rugby School (1816), ‘Great School Room’

With a sixth sense for trends, Ackermann also catered to the fashionable taste for appreciation of picturesque scenery, and for books that allowed the armchair traveller to view landscapes with picturesque qualities and their inhabitants (including the clans of the Highlands). He published armchair tours of the picturesque beauties of the Rhine, and the Seine, and the coast of Ireland.

A Picturesque Tour of the Seine (1821), ‘Andeli’

Illustrations of the Landscape and Coastal Scenery of Ireland (1835), ‘Gap of Dunloe, Killarney’

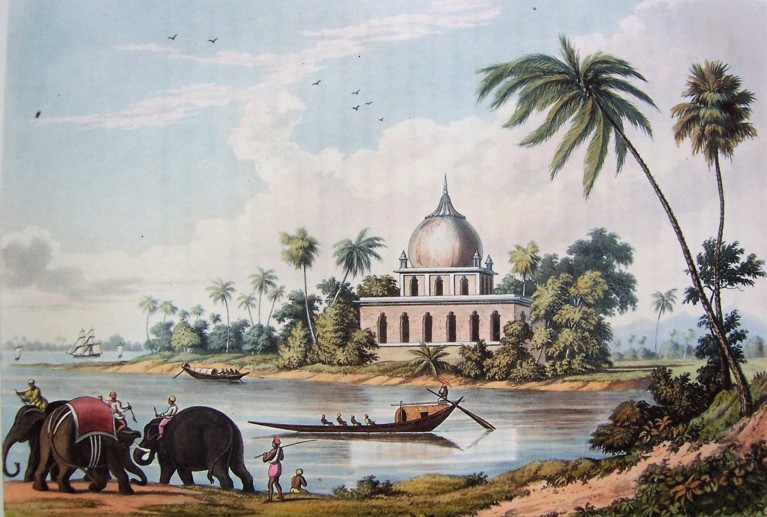

Further afield, Ackerman published a picturesque tour of the Ganges, and a history of Madeira with delightfully quirky illustrations.

A Picturesque Tour along the Rivers Ganges and Jumna (1824)

A History of Madeira (1821), Getting about on Madeira by Hammock-Mobile

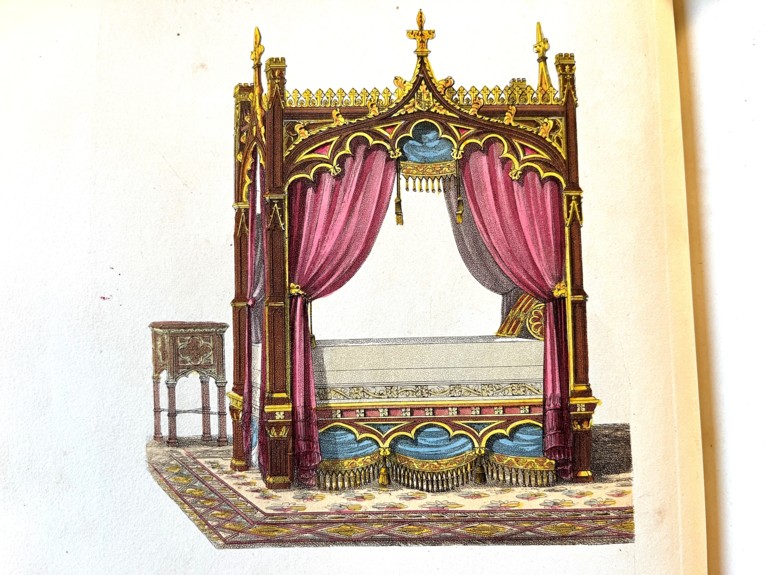

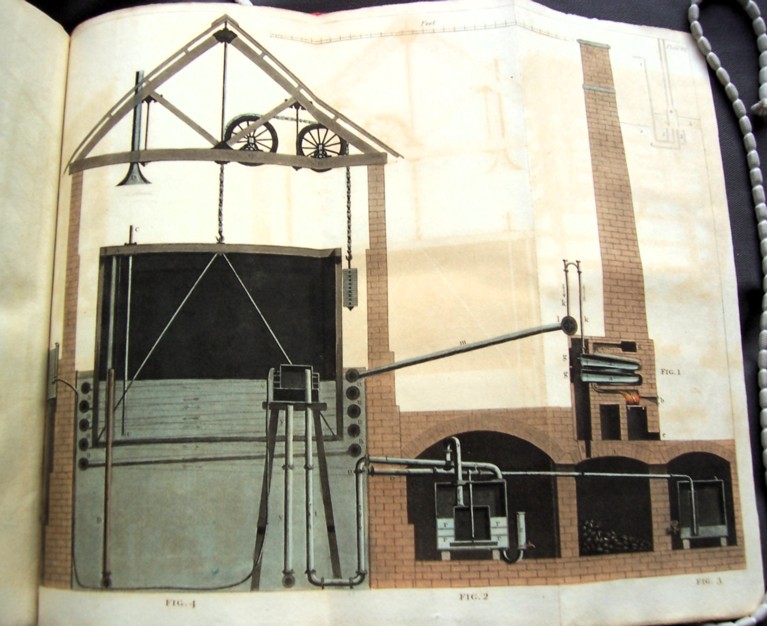

In none of these books were the texts written, or the illustrations drawn, engraved or coloured by Ackerman himself, but he employed the best artists and engravers of the day. This included publishing the cutting political and satirical caricatures of Thomas Rowlandson, as well as the more fastidious genius of Augustus Pugin, whose book of idiosyncratic designs for furniture in the ‘Gothick’ taste was published by Ackermann. Always the innovator, Ackermann’s shop on the Strand was illuminated by gas lighting, on which Ackermann published a book, and his own promotion of gas lighting furthered its wider acceptance at the time.

Augustus Pugin, Gothic Furniture, ‘Gothic Bed’

F. Accum, A Practical Treatise on Gas-Lighting (1816), illustrating gas-lighting machinery

He expanded into Latin America, where he supported the liberation movements, and published 100 books in Spanish (but this proved unprofitable and he burned his fingers). Perhaps akin to an obsession with cars in modern times, Ackermann’s engagement with carriage design never left him: in one year he designed both the carriage in which the Pope rode to Napoleon’s self-coronation as Emperor, and the elaborate hearse and the emblems on the coffin for the state funeral of Admiral Lord Nelson. With his inventiveness, his eye for design, and his sheer flair for business, Ackermann may be seen as a pioneer of modern publishing and illustration – and the fruits of that can be seen in the illustrated books in Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection that Ackermann and others published.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

Images: Clare Chippindale