Blog

1 November 2023

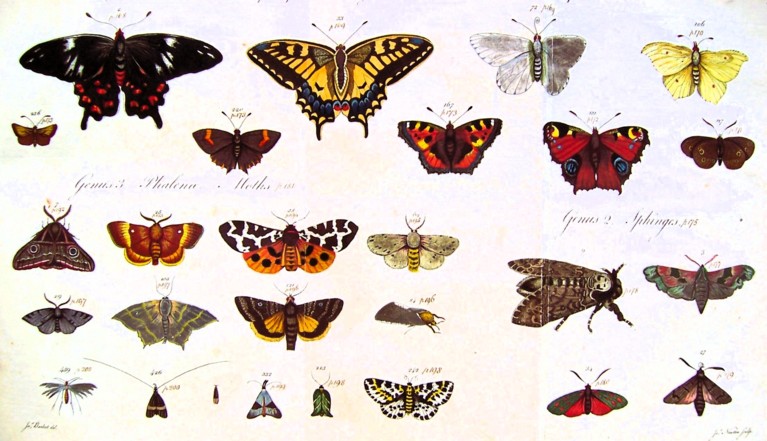

James Barbut, Les Genres des Insectes de Linne (London, 1781)

Now that we’ve said goodbye to the sight of butterflies for another year, the colour-plate images of their beauty in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century illustrated books – such as those in Emmanuel’s Library – are a potent reminder of their significance for so many past collectors and artists, and for those skilful individuals who managed to be both naturalists and artists. Across many cultures, the butterfly’s emergence from the chrysalis, and its ultimate derivation from a caterpillar, has symbolised transformation and rebirth, the triumph of spirit over the material and, in Christian tradition, the hope of resurrection. Yet there is always a painful sense too that the butterfly’s exquisite beauty is so evanescent.

Even the selection of illustrated books about insects in Emmanuel’s collection can represent the passionate interest, even ruinous obsession, of what we would now describe as amateur collectors of insect specimens. The earliest in our collection is Eleazer Albin (d. 1742?), possibly a German immigrant but by 1708 living in Piccadilly with his family. Initially a teacher of painting in watercolours, he became fascinated by natural history and published illustrated books on English insects, birds, and ‘spiders and other curious insects’. Albin prided himself on drawing specimens from life: his A Natural History of English Insects (1720) is ‘curiously engraven from the life: and (for those who desire it) exactly coloured by the author’. Albin’s illustrations of caterpillars munching on their favourite plants, attended by the moths that they become, are both elegant and skilful.

Eleazer Albin, A Natural History of English Insects (1720)

The text observes that the caterpillars who feed on the marsh plant fall off so often that they have developed a powerful backstroke to get them back to the plant stem. Albin acknowledges the participation of his daughter Elizabeth in drawing and painting for his A Natural History of Birds (1731-8), and appeals to fellow enthusiasts for more specimens: ‘Gentlemen … send any curious birds to Eleazar, near the Dog and Duck in Tottenham Court Road ... '

Albin, English Insects

Albin, English Insects

Moses Harris, The Aurelian (1766)

Another who combined skills as an artist and engraver with interest in natural history was Moses Harris, whose The Aurelian: or Natural History of English Insects appeared in 1766. Some of his illustrations are very accurately observed, and evidently coloured by Harris or under his close supervision. Stemming from his work as a colourist, Harris also propounded a system of colours through his ‘colour wheels’ that demonstrated how a range of colours may be made from red, yellow and blue.

The Cork-born Edward Donovan (1768-1837) rarely ventured outside London, yet he published on insects from across the world. Donovan was both artist and engraver, and (with a team of employees) also a colourist – as well as an ardent student of the natural world. As well as a sixteen-volume Natural History of British Insects (1792-1813), he published An Epitome of the Natural History of the Insects of China (1798).

Edward Donovan, Insects of China (1798), ‘Papilio Hyparete’, ‘Found near Canton’

Donovan, Insects of China, ‘Papilio Pryanthe’, ‘Papilio Philea’

Donovan also produced the first book on The Insects of India and the Islands in the Indian Seas (1800) and was the first to deal with the insects of Australia in his Insects of New Holland (1805).

Donovan, Insects of China, ‘Phalaena Bubo … Zonaria … Pagaria’

Donovan, Insects of India and Adjacent Islands (1800), ‘Papilio Ulysses’, ‘Dutch Spice Islands’ [Indonesia]

So how did Donovan do all this from his home in London? He was an avid collector and purchaser of specimens brought back by travellers – so much so that he even started his own Museum and Institute of Natural History, open to the public on payment of one shilling and displaying hundreds of cases of his specimens. Alas, the venture did not pay off, and Donovan’s pursuit of costly purchases of specimens so impoverished him that he eventually died penniless, leaving his large family destitute.

More successful in worldly terms was John Westwood (1805-1893), whose earlier amateur interests in both insects and in illustration later led to his becoming one of the first entomologists with an academic position at Oxford.

John Westwood, Oriental Entomology, ‘Papilio Icarius’, ‘Assam’; Butterflies ‘From the Torres Straits Islands’

But again, these splendid illustrations to his Cabinet of Oriental Entomology (1848) – ‘being a selection of some of the rarer and more beautiful species of insects, native of India and the Adjacent Islands' – are based on specimens in the collections of other naturalists.

Westwood, Oriental Entomology, Butterflies from modern-day Bangladesh

This was a collaborative fraternity of students of natural history, and Westwood collaborated with Edward Doubleday (1810-1849) on his Genera of Diurnal Lepidoptera (1846-50).

Westwood, Oriental Entomology, Butterflies found in the Himalayas

Edward Doubleday, Diurnal Lepidoptera, ‘Pavonia Rusina, Pavonia Ajax’

‘He had a butterfly mind’ is one of the less positive associations of butterflies, hardly shared by the extraordinary application of these various artists who were also students of natural history. Their lasting accomplishment in recording their butterflies is a kind of defiance of the evanescence of their subject.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

Images by Helen Carron, College Librarian