Blog

5 October 2023

Mrs Edward Bury, A Selection of Hexandrian Plants (1834), ‘Crinum augustum’. Bury was the artist but Robert Havell engraved and coloured the plates.

In any collection of nineteenth-century illustrated books such as Emmanuel is fortunate to possess, there will be ‘flower books’. A significant number of such books of botanical illustration are the work of largely unsung women artists, who display extraordinary painterly skills – as well as a reverent attention to nature – in so patiently recording their observations of plants and flowers. Often published anonymously and frequently sidelined, their work quietly advances a wider knowledge of botany, enlisting beauty in the greater understanding of nature (and in many cases also educating their readers in how to paint the same flowers and foliage for themselves).

The stunningly large and brilliantly coloured lilies of Priscilla Bury’s Hexandrian Plants (1834) reflect contemporary excitement among plant collectors at such exotic new plant imports blooming in their hothouses in and around Liverpool in the 1830s. At much the same time, the Irish botanical artist Catherine Teresa Cookson (of whom little is otherwise known) catered to such a taste for exotic flora in her Flowers drawn and painted after nature in India (c.1835).

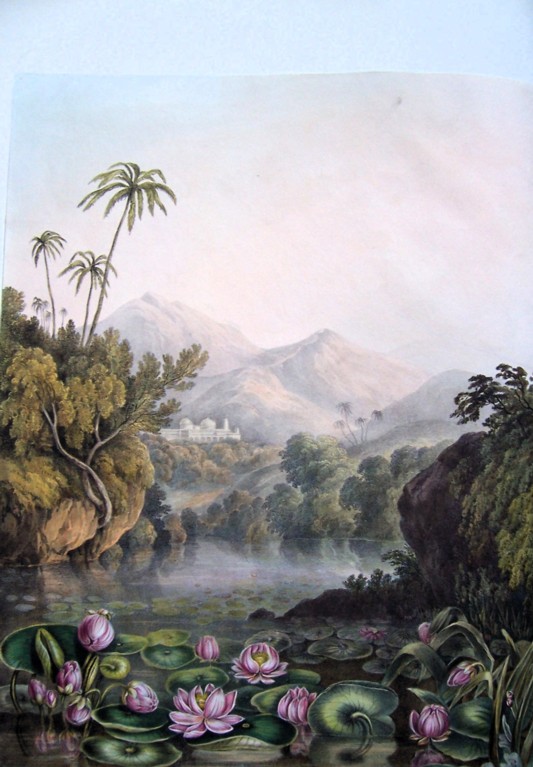

Catherine Teresa Cookson, Flowers drawn … in India (c.1835), ‘A View taken in INDIA, of the LOTUS growing in water’

Cookson, ‘The White Plumieria’

But the impetus to teach a book’s users how to undertake botanical illustration for themselves will tend necessarily to focus on more accessible flora. The splendid illustrations in Studies of Flowers from Nature (1818-1820) by ‘Miss Smith’ are accompanied on the facing page by helpful instructions on the particular paint colours to be used in copying the image. A second set of flowers drawn only in outline is also included for colouring in. Like a number of other female botanical illustrators, Miss Smith dedicates her book to a female patron, George III’s daughter Princess Elizabeth, herself an accomplished artist. Miss Smith has never been identified but may have been a teacher in a girls’ boarding school near Doncaster.

Miss Smith, Studies of Flowers from nature (1818-1820), ‘Camellia’

Anne Everard, Flowers from Nature (1835), ‘Purple foxglove’

Anne Everard’s Flowers from Nature … with Instructions for Copying (1835) also accompanies its thirteen hand-coloured lithographed plates with precise directions. For the purple foxglove: ‘Damp the paper with warm water and shade the corollas with a mixture of Prussian Blue and Lake; put a wash of carmine over them, and when nearly dry another of cobalt …’ (and so on for another eight lines of print).

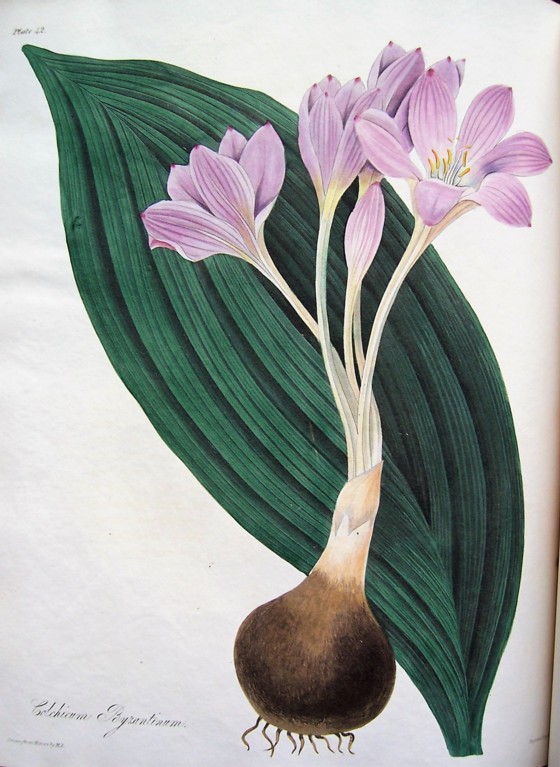

Some women artists left their drawing and painting to be engraved or lithographed by men, as with Margaret Lace Roscoe’s Floral Illustrations of the Seasons (1831), ‘From Drawings by Mrs Edward Roscoe’.

Margaret Roscoe, Floral Illustrations of the Seasons (1831), ‘Colchicum byzantinum’

But other women artists engaged in, and hence controlled, the whole process themselves, as is shown by two illustrated books themed around the flowers that are mentioned by celebrated poets. In her The Flowers of Milton (1846) Jane Elizabeth Giraud is building on the success of her The Flowers of Shakespeare a year before.

Her method was to draw the originals, then have them lithographed, and finally hand-colour the lithographs herself.

Jane Elizabeth Giraud, The Flowers of Milton (1846), illustrating lines from Milton’s ‘Lycidas’ that mention the musk rose, woodbine, cowslip and daffodil

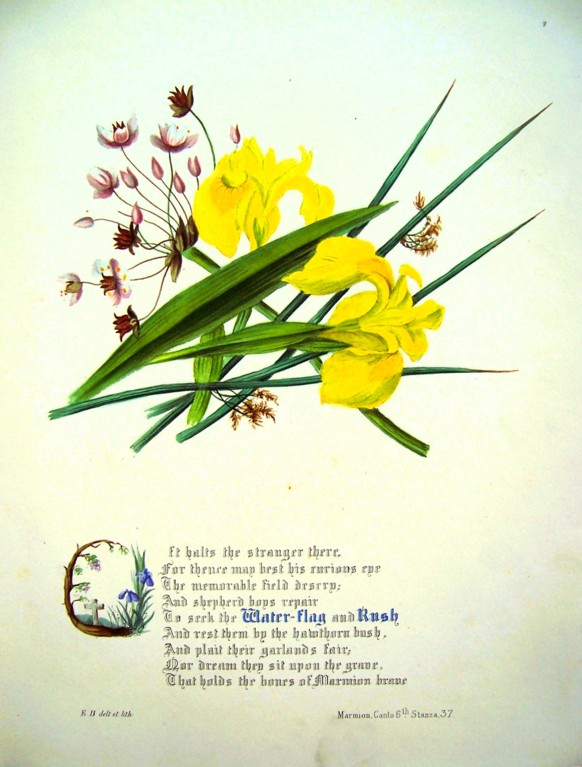

Elizabeth Bartlett, The Flowers of Scott (1852), illustrating lines from Sir Walter Scott’s ‘Marmion’ mentioning the water flag and rush

In Elizabeth Bartlett’s The Flowers of Scott (1852), thirty-five lithographic plates illustrate flowers that occur in the poems of Sir Walter Scott, and Barlett indicates on each plate that she has both drawn and lithographed them (‘E.B. delt. et lith.’).

Anonymous publication by women artists is well exemplified by Ten Lithographic Coloured Flowers by a Lady (Edinburgh, 1826-1832). This is actually forty fine plates published in four sets of ten. The list of subscribers – headed by the Duchess of Hamilton and the Lord Provost of Edinburgh – is entirely Scottish, but the ‘Lady’ artist remains anonymous to this day.

Ten Lithographic Coloured Flowers by a Lady (1826-32), ‘Primula auricula’

Rebecca Hey, The Spirit of the Woods (1837), ‘Mountain Ash’

In Rebecca Hey’s The Spirit of the Woods (1837) the title page makes no mention of Mrs Hey by name, although the preface refers to its author as female. There are 26 hand-coloured plates, presenting what is one of the early encyclopaedias of wild trees. Her earlier The Moral of Flowers (1833) acknowledged that the drawing and engraving had been done by men, but here are emphasized ‘the drawings for the illustration of the work, which the author herself has ventured to execute from nature and which she trusts will be found botanically correct’.

A prolific woman author and illustrator on botanical subjects was Jane Loudon (1807-1858), although before she started on that career she had already published, aged only 20, a novel that is sometimes seen as a pioneer and precursor of science fiction: The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827). (Reader, it’s a reincarnation of the Pharoah Cheops, not a dystopian matriarchy). Having reviewed The Mummy! John Claudius Loudon, the celebrated (and much older) Scottish garden designer, horticulturalist and author sought out the author of The Mummy! and they married six months later. Spotting a gap in the market for accessible books about how to garden, Jane Loudon’s books were illustrated with her own botanical paintings, which show a strong feeling for both colour and detailed botanical record.

Jane Webb Loudon, The Ladies Flower Garden of Ornamental Perennials (1846), ‘Peonies’. Loudon’s page layouts modelled on a bouquet were imitated and influential on décor.

Ladies Flower Garden, ‘Campanula’

These gardening books, directed at female readers, empowered countless women to take possession of their worlds through the creating of their own gardens, inspired by the information and the compelling illustrations in Mrs Loudon’s books. Eleven such books were published, and she also founded The Ladies Magazine of Gardening in 1842.

Jane Webb Loudon, British Wild Flowers (1847), a selection including ragwort, chamomile, yarrow, knapweed, musk thistle, hawkweed, succory

Fanny Elizabeth de Mole, Wild Flowers of South Australia (Adelaide, 1861), ‘Westringia rosmarinifolius and Cheiranthera linearis’

Jane Loudon’s sheer productivity in her life of only fifty years is astonishing, while in a much shorter life Fanny Elizabeth de Mole (1835-1866) produced the first book recording the flora of the South Australia colony. Her line drawings were sent to England for lithographing and the plates then returned to Australia, so that Fanny could colour by hand the one hundred copies each containing twenty plates.

‘Man … cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower’, in the words of the funeral service in the Book of Common Prayer. Part of the fascination of these books is that they preserve enduringly the beauty of flowers that so soon will have faded and represent the skilled life’s work of many undervalued women artists.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

Images by Helen Carron, College Librarian