Blog

2 August 2023

After a day’s hunting, John Mytton takes a shortcut home, straight across the lake (Life of John Mytton, 1837)

Behind the concept of eccentricity is the notion that normalcy and conventionality are at and of a centre, from which the eccentric diverges outside. In Emmanuel’s collection of colour-plate books are a group illustrating the lives of various fictional (male) types, including the squire, the nobleman, the actor, and the sportsman. These lives depict the enjoyably exaggerated but essentially expected characteristics of the bluff squire, the improvident nobleman and so forth.

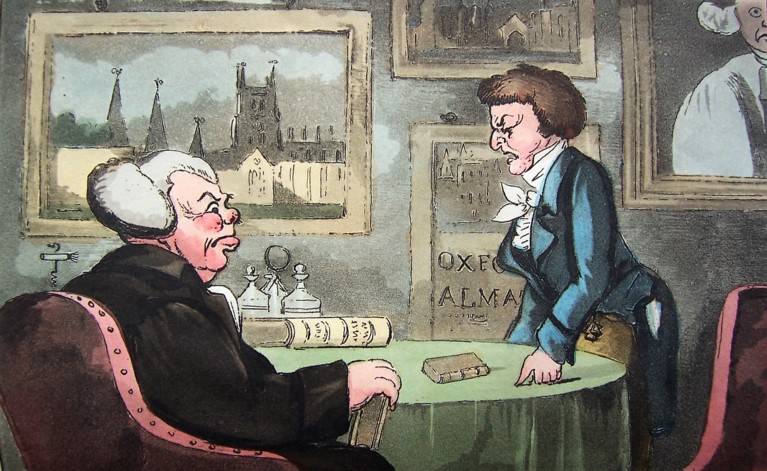

The Old English Squire (1821) by John Careless views its ‘Jovial Gay Fox Hunter, Bold, Frank and Free’ in a satirical light. Cartoonish faces are coarse-featured and bodies lumpy and graceless, as the dim squire clumsily tries to ape his betters and follow fashion, including going up to Oxford and splitting the seat of his trousers while shooting.

‘Crammed at College by his Tutor for a Degree’ and ‘Meets with a Small Accident’ (both from Old English Squire)

At the other extreme is the chilly elegance of George Dawes’ The Life of a Nobleman (1825), which in three pamphlet picture-books of illustrations charts the decline of a wealthy young nobleman, through plates showing betting at the races, a gambling house, a ‘night house’ or brothel, signing a loan agreement with a (obviously Jewish) money-lender, a duel, and a sickbed.

‘The Night House’ and ‘The Duel’ (both from Life of a Nobleman)

What was this book for? Perhaps useful to leave out for perusal by one’s wayward son and heir.

Pierce Egan’s The Life of an Actor (1825) can be realistic, as when depicting the actor manager fixating on his script, oblivious of his tattered shirt and of his hard-pressed wife trying to get the washing dry in a rented room.

‘The Apartment of an Itinerant Manager’ (Life of an Actor) and ‘Taking Eggs from Rooks’ Nests’ (Life of a Sportsman)

The Life of a Sportsman (1842) is a beautifully illustrated account by ‘Nimrod’, the pseudonym of C. J. Apperley, a celebrity sports journalist of the day. But since most of the sport illustrated is fox-hunting – which may run the risk of offending you, dear reader – a plate showing bird-nesting from rooks’ nests is selected here.

Nimrod chronicles altogether more extreme enthusiasms in his account of a real-life celebrity eccentric, Memoirs of the Life of John Mytton Esq … Eccentric and Extravagant Exploits (1837). Mytton was only two when he inherited estates in Shropshire and Wales. Expelled from Westminster (for fighting a master) and from Harrow, he then terrorized a series of private tutors, leaving a horse in the bedroom of one. Reputedly Mytton took 2,000 bottles of port to sustain him when he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, vowing to read only the Racing Calendar and the Stud Book. It was a brief stay.

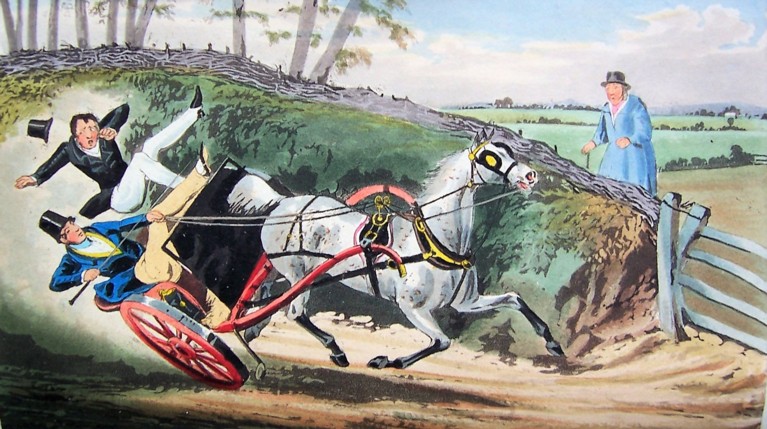

Mytton courted self-destruction, invited and positively enjoyed accidents, played outrageous pranks, and paid no more attention to cross-roads and corners than he did to creditors. He hunted in only the thinnest clothes, hunted wild fowl through snow in his shirt, and once hunted ducks over the ice while stark naked. While driving someone in a gig (a fast light vehicle) and learning that his companion had never been in a gig that overturned, he deliberately overturned the gig (‘What a damn slow fellow you must have been all your life’).

‘What? Never upset in a gig?’ and 'I wonder whether he is a good timber jumper!’ (both from Life of Mytton)

When driving horses tandem (one in front of the other) he tried to make them jump a closed turnpike gate – with predictable mayhem as the result.

Mytton once rode into his own dining room astride and spurring his pet bear (which bit him viciously in return). He also plunged into the Severn and swam across.

‘A New Hunter! Tally Ho!’ and ‘He that calls himself a sportsman, let him follow me’ (both from Life of Mytton)

In order to win a bet, he rode his horse up the grand staircase of a hotel in Leamington Spa and then horse and rider leaped from a balcony into the street below. His favourite horse Bayonet had the run of the house and would lie down in front of the fire with Mytton, who declared he did not believe in a heaven from which animals were excluded. Mytton’s first wife died after two years; his second ran away after ten years.

‘A perfect stranger to the science of economy’, Mytton disdained managing money and was open-handedly generous, probably running through a fortune of £20,000,000 in today’s money. Several thousand pounds once blew out of his carriage window as he drove back from the races. He spent around £750,000 in today’s money handing out banknotes to voters in order to be elected MP for Shrewsbury in 1819, but found the House of Commons too boring to stay for more than thirty minutes. He thought nothing of driving home at night across country rather than by the roads, and, when plagued by a persistent hiccup, Mytton madly decided to ‘frighten it away’ by setting light to his nightshirt. The hiccup stopped, but Mytton was badly burned.

‘How to cross a country comfortably after dinner’ and ‘Damn this hiccup!’ (both from Life of Mytton)

Mytton looms large as ‘this half-mad, hunting hunted creature’ in the pioneering study The English Eccentrics (1933) by the poet Dame Edith Sitwell (herself a considerable eccentric in her day). Yet ninety years later a more serious diagnosis than eccentricity might seem more appropriate today. Mytton died of delirium tremens aged 38 in the King’s Bench debtors’ prison in Southwark, having lost everything but his friends. Depending on reports, two or three thousand people attended his funeral. Streets, roads, a pub, a hotel, and a 72-mile bridleway through beautiful countryside are named after him in Shropshire.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)