Blog

4 July 2023

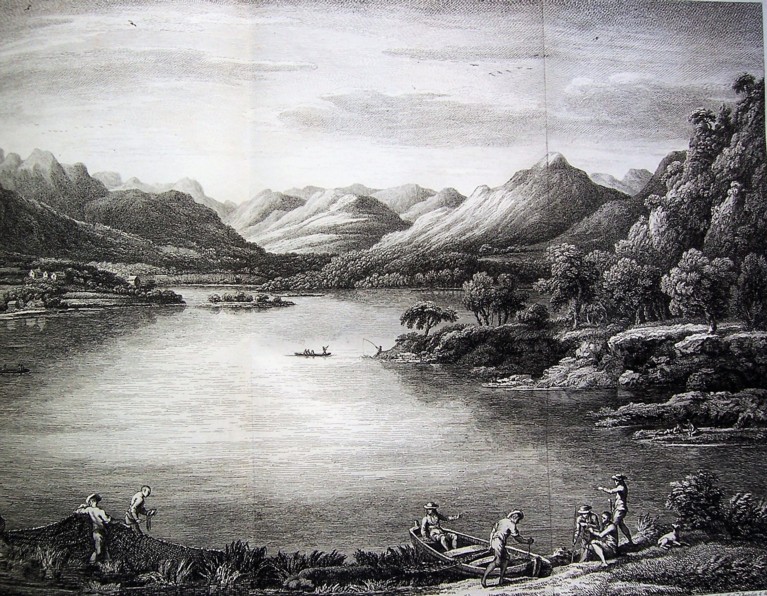

‘Keswick Lake (i.e. Derwentwater) from the north side of Castlelet’; William Westall, Views of the Lake and of the Vale of Keswick (1820)

Of all English scenery, that of the Lake District enjoys a unique esteem and, thanks to Graham Watson’s own love of the Lakes, the collection of illustrated books that he presented to Emmanuel includes a remarkable concentration of books recording the beauties of the Lakes, as well as a comprehensive range of guidebooks from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In what follows, the focus is on the depiction of the Lakes in the earlier years of Lakeland tourism, when the new process of aquatint enabled armchair travellers to savour scenes of natural beauty presented with fresh accuracy and sensitivity to colour, light and shade.

Writing before 1727, Daniel Defoe – author of Robinson Crusoe – could dismiss Westmorland as ‘a country eminent for being the wildest, most barren and frightful of any that I have passed over in England, or even in Wales itself’, and such had long been the general view of those ‘wild places’ of the island of Great Britain that are nowadays so treasured and protected. But a growing fashion for admiring picturesque scenery became within a short time the universal vision of the educated classes and changed perceptions of the Lake District for good. From the 1750s tourists visited the Lakes to enjoy the scenery, seeing their journeys as progress through a succession of pictures. As a tourist, one had to stand in the right place, or ‘station’, to attain the best view, and guides to such stations soon proliferated, blithely plagiarizing from each other – fifteen in the last quarter of the eighteenth century alone. A cult was born.

‘A View of the Head of Ulswater towards Patterdale’; William Bellers, Eight Views of the Lakes in Cumberland (drawn in the 1750s, republished 1774)

‘The Grange in Borrowdale’; Joseph Farington, Views of the Lakes (1789)

Early depictions of the Lakes were made by William Bellers in the 1750s, in awareness of picturesque conventions of seventeenth-century landscape painting in Italy. One of the earliest illustrated books about the Lakes is Joseph Farington’s uncoloured Views of the Lakes (1789), with descriptive text probably by Wordsworth’s uncle William Cookson. Farington’s views are notably typographically accurate, with no tweaking to appear more picturesque and were made from copper plates etched and engraved in the conventional way. One early exercise depicting the Lakes in aquatint is Select Views of the Lakes (1792), published in Liverpool by Peter Holland, a Liverpool artist about whom little is known. Also atmospheric are John ‘Warwick’ Smith’s Views of the Lakes (1791-5).

Peter Holland, Select Views of the Lakes (1792)

‘Rydal Water’; John ‘Warwick’ Smith, Views of the Lakes (1794-5)

Three ambitious colour-plate books on the Lake District, illustrated with aquatints, appeared within three years. William Westall was both artist and engraver for Views of the Lake and of the Vale of Keswick (1820), with text by the poet Robert Southey. (Keswick was an early centre and focus of the Lakeland cult). Westall’s attempts to convey distance, and how colour fades away eerily at twilight, are fine examples of what might be achieved in aquatint during its heyday.

Westall, Views: ‘Keswick Lake from Saddleback’

Westall, Views: Keswick Lake from the east side, at twilight

The two other books were T. H. A. Fielding’s A Picturesque Tour of the English Lakes (1821) and his Cumberland, Westmoreland and Lancashire Illustrated (1822).

Like Westall, Fielding was his own engraver, worked largely if not exclusively from his own drawings, and probably wrote the accompanying descriptive text himself.

‘Grasmere’; T. H. A. Fielding, A Picturesque Tour (1821)

‘Wyburn Water and Helvellyn’; Fielding, Picturesque Tour

And like any artists working in the Lake District, both Fielding and Westall necessarily developed an eye for depicting impending rain.

‘Grasmere Church and Helm Crag’; Fielding, Picturesque Tour

Westall, Views: ‘Keswick Lake from Barrow Common’

As we look at these depictions, it is helpful to recall that while the views may appear timeless, the experience of tourism could be focussed differently in different times. Not least because many modern routes in the Lake District did not yet exist, early tourism was different to what it became. Tourists largely stuck to the valleys and would ride more than walk. For a while the fells remained unroamed and the mountains unclimbed. One early fad of the picturesque was the enjoyment of ‘echo tourism’, savouring the sound effects of echoes artificially created. At Ullswater the Duke of Portland had a barge with six cannons, so as to enjoy the reverberations rolling through the valley, and the sounds of French horn, bassoon and clarinet heard across the water of the Lakes were also sought out by tourists, long before pursuit of the echo gave way to pursuit of the eco.

‘Skiddaw over Derwent Water’; Fielding, Cumberland … Illustrated (1822)

‘Skiddaw, from the Head of Lowdore Fall’; Fielding, Picturesque Tour

Such was the fashion for accounts of the Lakes that anything mentioned in print might suffer problems of unsought celebrity. In his A Fortnight’s Ramble to the Lakes (1792) Joseph Budworth glowingly described the beauty of Mary Robinson, fifteen-year-old daughter of the landlord of the Fish Inn in Buttermere – and she promptly became a tourist attraction. Uneasy at the bother he’d caused, Budworth then published an account (rather ironically in The Gentleman’s Magazine) of how he had revisited Buttermere and informed Mary: ‘You are not so handsome as you promised to be; and I have long wished by conversation like this to do away what mischief the flattering character I gave of you may expose you to.’ Too late, alas – before this was published, poor Mary married someone passing himself off as ‘The Hon. Alexander Hope’, actually John Hatfield, a notorious imposter and bigamist, who would be hanged for forgery at Carlisle in 1803. The tragedy of ‘The Maid of Buttermere’ was endlessly recounted, becoming a novel and a melodrama on the London stage. In Italy it would surely have become a bel canto opera.

‘Stickle Tarn near the top of Langdale Pikes’; Fielding, Picturesque Tour

‘Blea Tarn’; Fielding, Cumberland … Illustrated

After 1830, engraving on steel rather than copper enabled the proliferation of images of the Lakes, and numerous guidebooks would be regularly produced.

If you are planning to visit Emmanuel this Saturday, 8 July, you may be interested to know that Dr Helen Carron has curated an exhibition of Lake District books which are on show in the Graham Watson Room and the Library Atrium.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)