Blog

10 May 2023

Nayler, ‘Coronation of … George IV’: The King with his train borne by eight eldest sons of peers, supervised by the Master of the Robes. This elaborate train later suffered the indignity of ending up at Madame Tussauds, but was presented back to George V and used at coronations since 1911

Emmanuel Library’s special collections include books commemorating two of the most splendid coronations: those of Charles II in 1661 and of George IV in 1821. Not unlike Charles III’s coronation in 2023, those of George IV and of Edward VII (in 1902), took place after gaps of six decades since the previous coronation, allowing for significant reinvention.

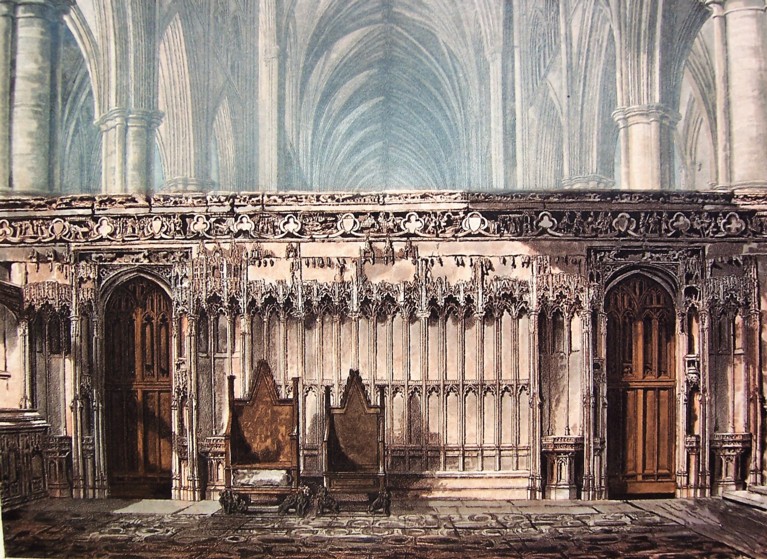

St Edward’s Chair, with the Stone of Scone, as it was in 1812, when it had been unused for over 50 years since George III’s coronation in 1761 (Rudolph Ackermann, ‘History of Westminster Abbey’)

Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, there was special moment in Charles II’s coronation as the new beginning of a re-established order. An enormous procession from the Tower of London to Whitehall on the day before the coronation was a carefully staged spectacle, projecting the restored King as magnificent yet accessible. Thousands of officials of the Royal Household and most of the nobility took five hours to process along the five-mile route, with the King bringing up the rear. The Entertainment of His Most Excellent Majestie Charles II, in His Passage through the City of London to His Coronation (1662) devotes ten pages to recording the participants in this great cavalcade. Its account of the coronation day also depicts the procession on foot from Westminster Hall to Westminster Abbey, which was long a part of the ceremonial (until it was dropped for William IV’s cut-price coronation in 1831 and never revived).

John Ogilby, ‘The Entertainment’, Procession through the City of London (Charles II can be seen on the left in the bottom line of the cavalcade)

Ogilby, ‘Entertainment’, Procession between Westminster Hall and Westminster Abbey (Charles II, beneath a canopy, in the bottom line)

Charles II’s route through London was marked by four triumphal arches (paid for the City of London). Each arch was nearly one hundred feet high, made of wood and decorated with mottoes and emblems. The four arches represented monarchy, naval power, concord and plenty, and pageants were presented at each arch to the King, who took a close interest in how his coronation was recorded for posterity in this book.

Ogilby, ‘Entertainment’, the Triumphal Arches of Naval Power and of Plenty (above and below)

Since the Cromwellian regime had sold off the ancient regalia to be melted down – including St Edward’s Crown that had supposedly survived from Anglo-Saxon times – new regalia were made for Charles II’s coronation, augmenting the sense of this occasion as a reinstitution.

Reports of many subsequent coronations so often mention what went awry on the day as to suggest that most were seriously under-rehearsed by later standards. Yet the core of the service remained constant ever since St Dunstan, as Archbishop, had devised the coronation of King Edgar at Bath in 973 AD. First, the new monarch is presented to and acclaimed by the people. The monarch swears an oath, is anointed, invested with regalia, crowned, and receives homage. The consort is then anointed and crowned.

George IV’s coronation remains by far the most extravagantly expensive – the spendthrift king aiming to outdo Napoleon’s coronation as Emperor – although it is now chiefly remembered for the fracas when his estranged queen, Caroline of Brunswick, tried in vain to enter the Abbey during the ceremony. The lavish scenes find a fitting record in Sir George Nayler’s huge book, The Coronation of … King George the Fourth (1823-1837), of which Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection holds a magnificent copy, the plates enriched with gold and silver.

Proceedings commence with the presentation of the regalia to the King in Westminster Hall.

The Dean and Prebendaries of Westminster bear the regalia to the King in Westminster Hall (Nayler, ‘Coronation’)

After this an immense procession of officials and peers forms up to transfer the regalia to the Abbey, preceded by the King’s Herb Woman and her six Herb Maidens strewing flowers.

The King’s Herb Woman with her Six Maids, strewing the way with flowers (Nayler, ‘Coronation’)

The standards of Ireland and Scotland being borne to Westminster Hall by Lord Beresford and the Earl of Lauderdale (Nayler, ‘Coronation’)

St Dunstan would still have recognized the key elements in the proceedings in the Abbey as George IV is crowned.

The Crowning of George IV’ (Nayler, ‘Coronation’)

There follows the swearing of homage, the moment illustrated being the joint homage of the King’s brothers.

The Homage (Nayler, ‘Coronation’)

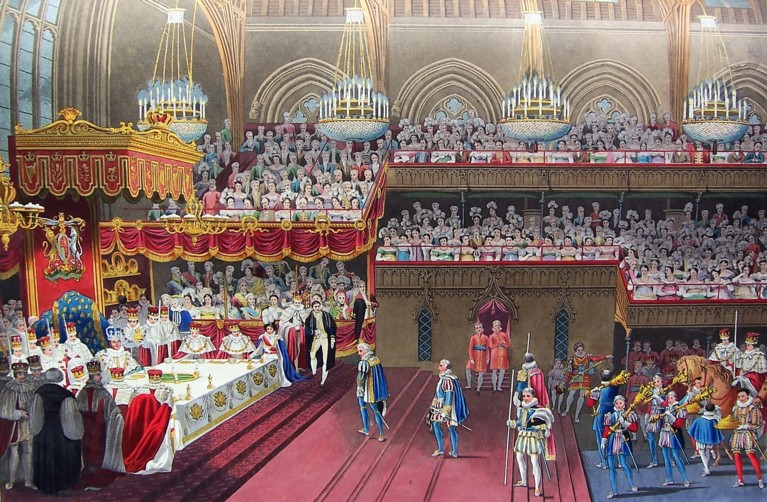

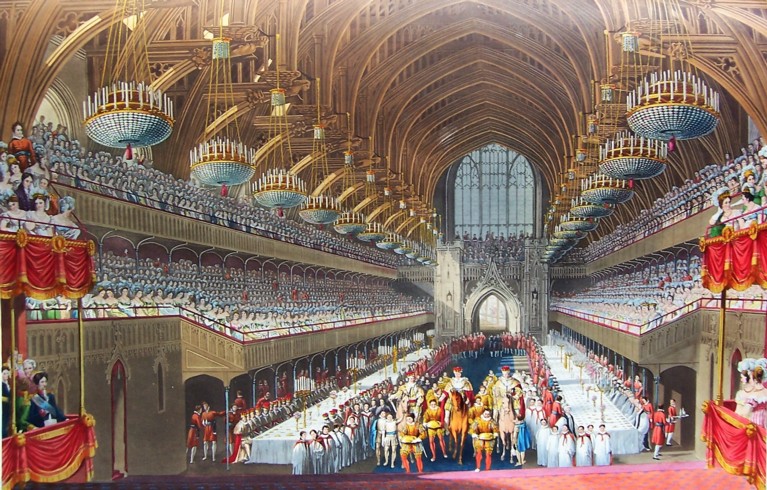

Two further plates depict the banquet in Westminster Hall that followed coronations. Perhaps strangely to our ideas, these too had a large paying audience on temporary scaffolds of raked seating. But the banquets were almost as much entertainment as the coronation.

The Coronation Banquet of George IV (Nayler, ‘Coronation’) (above and below)

The three officers of state – the Earl Marshall, the Lord High Steward and the Lord High Constable (the Duke of Wellington) – rode the full length of the Hall on horseback to escort the serving of courses.

And the King’s Champion rode into the Hall during the banquet to a flourish of trumpets, attired in armour, crowned with plumes of ostrich feathers, and flanked by the Earl Marshall and the Iron Duke, also on horseback. Three times – upon entering, halfway up the Hall, and in front of the dais – the Champion threw down the gauntlet (literally) and challenged to fight any who disputed the King’s right to the throne. At the close, the ravenous occupants of the scaffolds fell upon the leftovers and made off with any fittings they could carry.

Including the prior procession and the banquet, Georgian coronations required the king and queen to be present continuously for some twelve hours and were both ramshackle and exhausting. William IV tried in vain to abolish coronations altogether, and, although thwarted in this, insisted on a low-key event for himself. No more was heard of a King’s Champion, and Victoria’s coronation lasted a mere five hours.

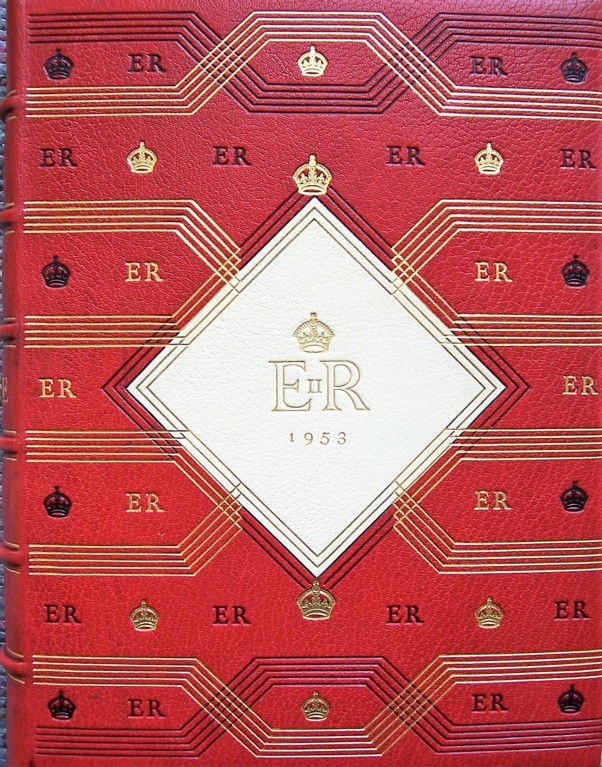

By the time of Victoria’s death, the model for her successor’s coronation was not Victoria’s long-past coronation but the grand public ceremonial and vast procession celebrating her 1897 Diamond Jubilee. The four twentieth-century coronations (in 1902, 1911, 1937 and 1953) – progressively better organized and with ambitious programmes of music – sought to project an image of the country past and present, placing new emphasis on engaging with a wider public. Yet the heart of the ancient rite in the monarch’s anointing and taking of the sacraments remains so personal to that individual, as well as of public significance, that there are still misgivings about broadcasting this. Emmanuel is fortunate to have a replica of the Bible, in its gorgeous mid-century binding, upon which Elizabeth II swore the oath that she kept for the rest of her long life.

Mr Punch: ‘Your coronation awaits Your Majesty’s Pleasure, but you are already crowned in the hearts of your people’ (‘Illustrated London News’, 6 February 1901)

No 22 of 25 copies of the Bible, on the first of which Elizabeth II swore the oath at her coronation on 2 June 1953. Bound by Sangorski and Sutcliffe, to a design by the artist and illustrator, Lynton Lamb (Graham Watson Collection)

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

Images by Helen Carron, College Librarian