Blog

16 March 2023

Who can predict a best-seller – the book that catches the moment, not only becoming a minor classic of its day but spawning a crop of illustrated spin-offs? So it was with James Beresford’s satirical The Miseries of Human Life (1806), cast as a dialogue of ‘groans’ between two old carmudgeons, Mr Samuel Sensitive and Mr Timothy Testy, who review the petty outrages, minor humiliations and tiny discomforts ‘that fastidious flesh is heir to, in this dislocated world of ours’ – with Mrs Testy supplying ‘A Few Supplementary Sighs’ from a woman’s perspective.

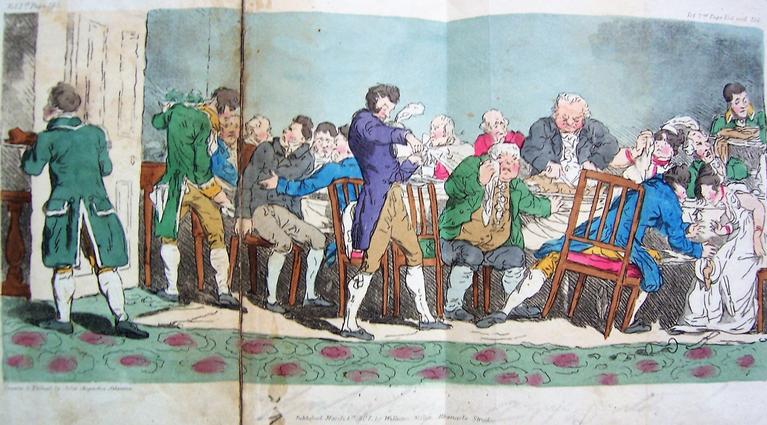

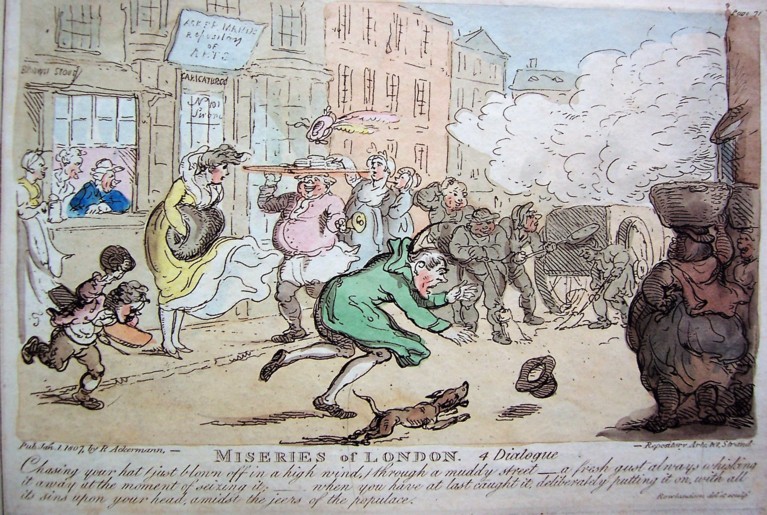

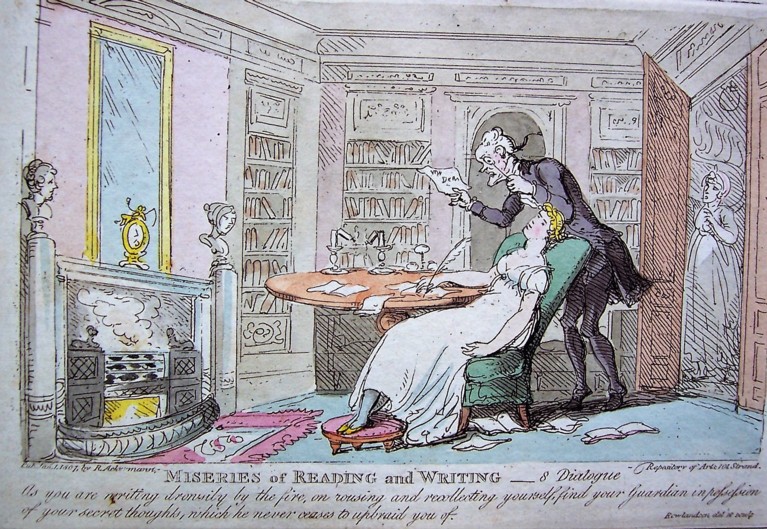

Illustrators immediately saw potential in the theme of Miseries for cartoon-like depictions of the comic indignities and discomfitures inflicted by human foible, by accident and circumstance. Within a year, two colour-plate books had appeared, of which Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection holds copies: Sixteen Scenes Taken from the Miseries of Human Life, By One of the Wretched (actually by J. A. Atkinson, 1807) and Thomas Rowlandson’s Miseries Complete in Twelve Dialogues (1807).

‘Miseries of London’ include ‘chasing your hat (just blown off in a high wind) through a muddy street – a fresh gust always whisking it away at the moment of seizing it’, all this happening ‘amidst the jeers of the populace’. Other miseries of London include being cannoned into by inattentive fellow pedestrians (little changes).

Above; Pl 2: ‘Miseries of London’ (Rowlandson). Below; Pl 3: ‘Miseries of Games and Sports’ (Rowlandson).

‘Miseries of games and sports’ include ‘in skating – slipping in such a manner that your legs start off in this unaccommodating posture – from which however you are soon relieved by tumbling forwards on your nose, or backwards on your skull’.

Miseries of newly-fashionable seaside holidays include: ‘ploughing knee-deep, in sand, shells, or pebbles for a whole morning together, to grub for marine curiosities, which you do not find’. You long for a horse to take you home, but must compromise on a donkey, which then refuses to budge.

Above; Pl 4: ‘Miseries of Watering Places’ (Atkinson). Below; Pl 5: ‘Miseries of the Country’ (Rowlandson).

Among ‘Miseries of the Country’ is a walk after heavy rain when ‘one shoe suddenly sucked off by the boggy day, and then, in making a long and desperate stretch (which fails) with the hope of recovering it, the other [shoe is] left in the same predicament’. The writer groans: ‘the second stage of ruin is that of standing or rather tottering in blank despair, with both bare feet planted ankle deep in the quagmire’.

Other ‘Miseries of the Country’ stem from male attempts to impress the opposite sex, as when ‘in attempting to spring carelessly, with the help of one hand, over a five-barred gate, by way of shewing your activity to a party of Ladies behind you (whom you affect not to have observed), [and] blundering upon your nose on the other side’.

Above and Below; Pls 6 and 7: ‘Miseries Miscellaneous’ (Atkinson).

Another plate shows the misery of ‘handing a Lady out of a boat along a rickety plank – sacrificing your own footing to save hers’, although the text advises unchivalrously ‘Seize, seize the plank thyself, and let her sink…’

But indoors teems with ‘Miseries Domestic’, such as ‘Squatting plump on an unsuspected cat in your chair’, or a servant’s dropping the tea-urn just as he is passing you, breaking your leg while scalding you with boiling tea.

Above and Below; Pls 8 and 9: ‘Miseries Domestic’ (Rowlandson; Atkinson).

‘Miseries of the Table’ include the mortification of inviting friends to ‘partake of a fine hare haunch’ which you judge perfect but which they find rank, and ‘which is no sooner brought in than the whole party, with one nose, order it to be taken out’.

Above and Below; Pls 10 and 11: ‘Miseries of the Table’ and ‘Miseries of Travelling’ (Rowlandson).

‘Miseries of Travelling’ involve getting drenched en route to a dinner engagement and the mortification of ‘looking like a full or empty sack’ in clothes borrowed from one’s host, ‘he being either a Dwarf or a Giant’.

Some miseries voiced by female speakers question the control of their thoughts and lives by men. One is the misery of ‘as you are writing drowsily by the fire, on rousing and recollecting yourself, find your Guardian in possession of your secret thoughts, which he never ceases to upbraid you of’.

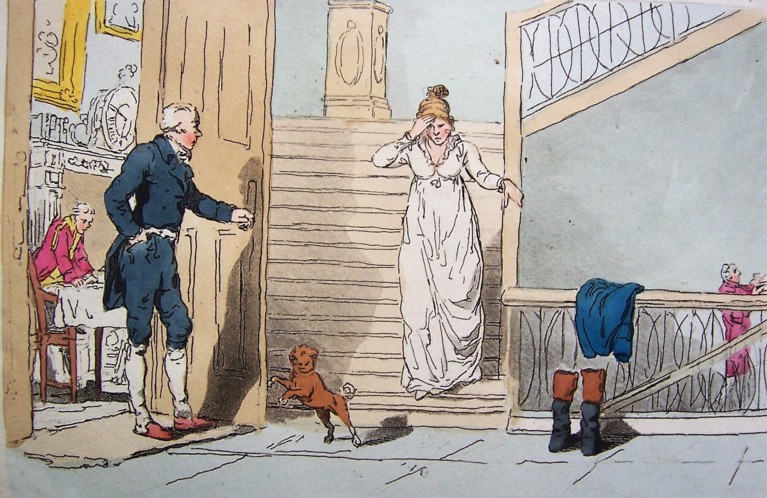

Above; Pl 12: ‘Miseries of Reading and Writing’ (Rowlandson). Below; Pl 13: ‘Miseries of Fashionable Life’ (Atkinson).

‘Miseries of Fashionable Life’ include ‘on crawling down to the breakfast room, with a gambling head-ache upon you already, encountering the figure of your husband’.

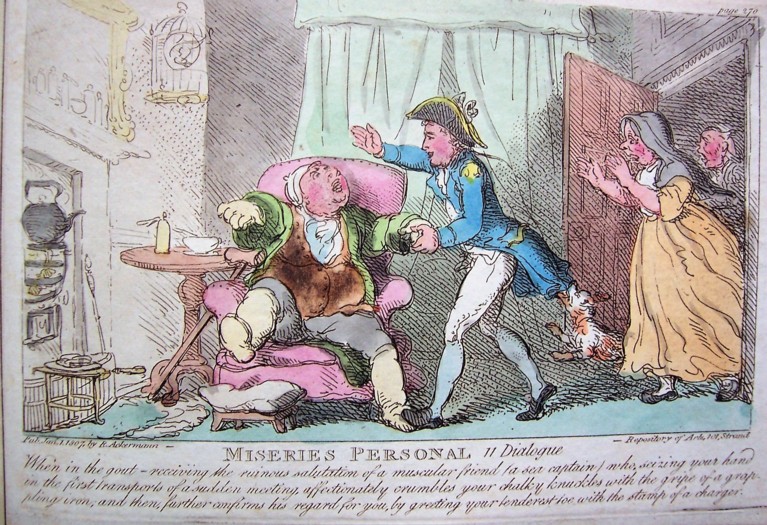

The miseries of being a gouty invalid greeted by a strapping naval visitor who unthinkingly squeezes the invalid’s hand in a vice-like grip while treading on his ‘tenderest toe’ is an emblem of the world-view in these illustrated books – so alert to all the insults, agonies and mortifications that the sensitive soul suffers in daily life.

Above and Below; Pls 14 and 15: ‘Miseries Personal’ and ‘Miseries Miscellaneous’ (Rowlandson).

Perhaps the greatest misery is being surrounded by fools, and it is no accident that it is a young woman, possibly on some secret errand of the heart, who has ‘the necessity of sending a verbal message of the utmost consequence by an ass, who, you plainly perceive, will forget (or rather has already forgotten) every word that you have been saying’.

These books may appeal because, while the miseries they record are supposedly minor, we know that such incidents can irritate, humiliate and wound us, and there is a satisfaction in seeing those miseries acknowledged here as inseparable from life.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)