Blog

16 February 2023

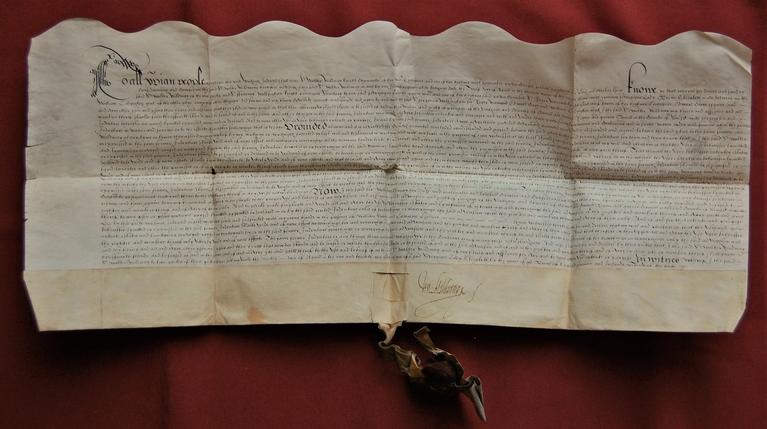

Emmanuel College owns some two dozen advowsons. These incorporeal hereditaments, to use the legal jargon, confer the right to present a clergyman to a parish ‘living’. As the college’s founding ethos was the training and dissemination of a Puritan priesthood, the possession of an adequate number of clerical livings to which it could appoint its own men was of prime importance. Within a few years of its foundation the college had already acquired a dozen advowsons, and it defended its title to these valuable possessions against any challengers. It was not always successful.

The advowson of Puddletown, Dorset, was one of three granted to Emmanuel in 1586 by Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, an old crony of the college’s Founder, Sir Walter Mildmay. In 1639 Lord Huntingdon’s great-nephew, the 5th Earl, contested the college’s right of presentation to all three livings, the issue being whether his great-uncle had held them in fee simple, or tail, which would have affected his right to dispose of them. The college managed to hang on to two of the advowsons, but judgement was given against it in respect of Puddletown.

Failure to make a promise watertight was the cause of a bitter dispute about the living of Beckley, Sussex. The incumbent, Emmanuel graduate John Holman, also owned the right of presentation. He told the college in 1657 that he intended to grant it the Beckley advowson, but never sent any legally binding confirmation. The college was later assured by a go-between that a deed of gift had indeed been drawn up and was in safe hands, but when Holman died in 1673 his executors declared that they could find no trace of such a grant. Convinced that Holman’s heir had suppressed it, the college began legal proceedings, but either dropped or lost its case a year later.

A testator’s woolly wording prompted a lawsuit many years after his death. In 1704 Henry Mildmay, a descendant of the Founder, had bequeathed to Emmanuel the next three turns of the advowson of Henstead, Suffolk. The college duly exercised its right, but when the third appointee finally died in 1792, Mildmay’s heirs demanded the reversion. The college disputed this claim, on the grounds that the ‘expression used by the Testator is so inaccurate & defective that it is impossible to say with any certainty what he meant’. Despite receiving mixed advice about the wisdom of taking legal action, the college went ahead, but its cause was unsuccessful.

Perhaps the most galling, and certainly the most embarrassing, case, involved Queen Camel, Somerset. This was one of two advowsons presented to the college in 1588 by Sir Walter Mildmay. He revoked the Queen Camel grant on 9 April 1589, but re-conveyed the living to the college two days later, via a clause in a title deed primarily drawn up to augment the other advowson. The reasons for this rigmarole are uncertain, but close to death and having made his will a few days earlier, Sir Walter may have been anxious to give the college a more secure title to the Queen Camel living. If so, his good intentions had precisely the opposite effect, for the Emmanuel authorities, rather incredibly, overlooked the re-conveyance, and considered the deed of revocation to be the Founder’s last word. Almost two centuries later, having discovered its error, the college sought legal advice about reclaiming the advowson, but was advised that its case was now ‘barred & without Remedy’. The resulting chagrin can only be imagined.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist