Blog

1 December 2022

At a time when the cameras in mobile phones enable anyone to record experience and environment with remarkable clarity, it is worth comparing our circumstances with those earlier times when young people were routinely taught to draw. There was no questioning the value of being able to record accurately, hopefully to catch a likeness, but also to frame a composition and so make a picture of what was seen.

Emmanuel’s collections of illustrated books appeal to the taste of users acculturated to value the making of a picture, and quite often with some education themselves in how to do so. One book in Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection is a kind of pattern book of studies of the rural poor. These preserve likenesses of people who might never normally be portrayed, but who were drawn to provide models that could be copied by budding young artists to supply the figures in their landscapes.

William Henry Pyne’s Rustic Figures (London, 1817) prints a set of such figures, ‘in Imitation of Chalk’ drawings, none of which is captioned but which illustrate the book’s recommendation to students to seek for nature by viewing the rural poor at their occupations.

The author’s introduction comments that ‘drawing the characters … of rustic figures’ is as different from drawing ‘the elegant or classic figure’ as the difference in their ‘manners and habits’. But the introduction insists ‘Not that the rustic is always devoid of dignity; but his is a dignity of a peculiar order, existing in nature, without either the elegance or the affectedness which may be derived from education’. A sympathetic eye has sketched the worn figures of the aged poor:

Women young and old look out at the viewer pensively, with little to smile about:

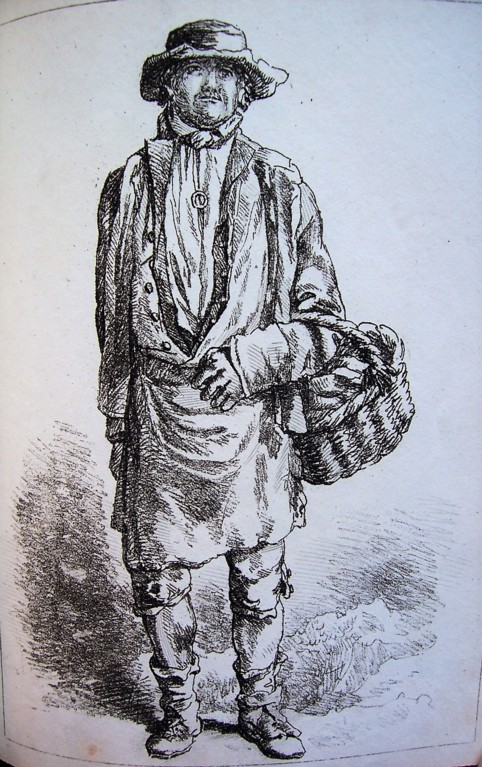

Men young and older meet the viewer’s gaze more bluffly:

Clothes and footwear are simple and basic, but not generally ragged and tattered. The author sees a distinction between drawing drapery on an elegant figure, which must be ‘so arranged as to fall in studied folds’ and follow the form of the limbs. By contrast, the folds in drapery on rustic figures, ‘being usually made of coarse materials’, may often ‘not indicate the limbs at all’. Some seated figures look conscious of being drawn; perhaps they were just glad to sit down for a while:

The introduction rules that ‘elegant heads, delicate hands and feet, and … languishing positions … cannot accord with the hardy habits’ of the rural poor. It declares that ‘nothing can be more absurd than to see a race of gods and goddesses with scythes and hay-rakes, attired in waggoners’ frocks and mob-caps’, yet the artist’s keen observation and humanity have actually discerned the dignity of labour in a labourer with a scythe and a girl with a net:

To draw such figures is favourably compared with work ‘long ago from the pencils of the Flemish and Dutch masters, inimitable in their way’ which (in the author’s view) is now being rivalled by English artists’ focus on such rustic figures:

The book’s introduction closes with a sales pitch advertising study aids for budding young artists: ‘To facilitate the study of rustic figures, the author of this work has modelled a number of characters, selected from the English peasantry, on a scale of eight inches in height; from which plaster-casts are taken; for the purpose of assisting young persons in acquiring the art of grouping, and to improve them in the study of light and shadow … These casts may be had at The Repository of Arts, 101 Strand’.

Whether or not any of these plaster models survive, this modest book, with its utilitarian ‘how to draw’ purpose, enables its examples of the rural poor of its day to live on.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)

Back to All Blog Posts