Blog

11 August 2022

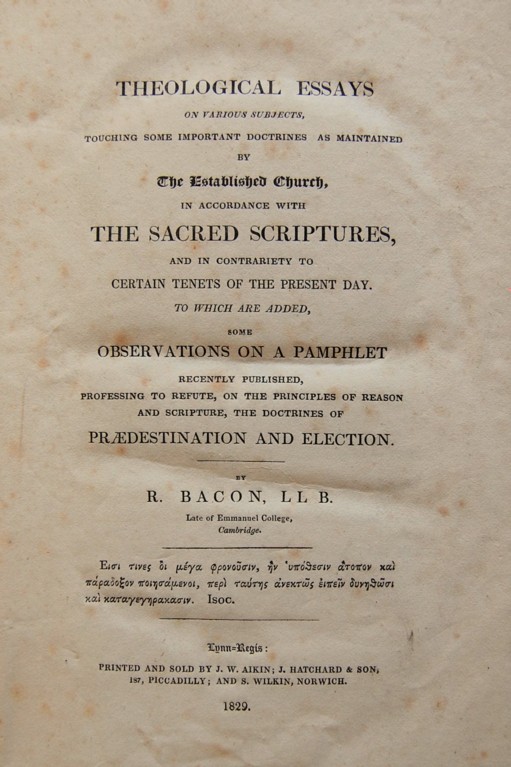

Above Left: Wolferton Church Above Right; Title page of work by Robert Bacon

Entertaining anecdotes about the college’s history abound, some more plausible than others. It is rarely possible to put them to a definitive test, but the case of Robert Bacon is an exception. Admitted to Emmanuel in 1799 when he was in his early 30s, Bacon graduated Bachelor of Laws in 1806. He later styled himself LL.D. Following his ordination in 1802, Bacon amassed a clutch of parochial cures in West Norfolk, including the perpetual curacy of Fring, a small village nestling in a fold of the Norfolk Heights. From 1836 he was also rector of Wolferton, a low-lying parish near the Wash. The two villages are about seven miles apart as the crow flies, but more by road.

Bacon died in 1861, aged 95. During his long career he penned a number of ponderous religious tracts, including True Religion the Glory of a Nation, A due sense of religion productive of civil obedience, Christian Consolation, Strictures on Tractarian Notions and A scriptural view of the ordinance of baptism. A copy of his Theological Essays, printed by subscription in 1829, is held in the library at Emma, for the college was one of the subscribers.

In the archives’ correspondence files is a letter written many years ago by a potential biographer of Bacon, who represented him as a man whose ‘two chief concerns in life were his income, and how to increase it and his personal dignity and importance and how to record it for posterity’. Pluralism must have helped with the first of these ambitions, and crowd-funded publishing with the second; Bacon also apparently noted his pastoral achievements on the flyleaves of his parish registers. It was another sentence in the biographer’s letter, however, that particularly caught my attention: ‘Bacon used to ride to the top of the hill at Fring from which he could see the Wolferton tower and if there was no congregation the verger flew a flag and the Dr returned to Fring Parsonage’.

Knowing the locality reasonably well, this statement struck me as being highly dubious; not because there is now neither a parsonage at Fring nor a flagpole at Wolferton, for such things can pass away, but because of the lie of the land. The only way to be sure, though, was to see for myself by climbing the hill in question, which is crowned with a triangulation pillar. Having now ascended to this vantage point in varying weather conditions, I can confirm that it is impossible to make out Wolferton church, even on a clear day.

There are in any case other reasons to doubt the story. However turgid the Revd Robert’s sermons may have been, it seems unlikely that the complete absence of a congregation was a regular occurrence at Wolferton. We are also asked to accept that the parishioners would have sat patiently in their pews while the elderly rector careered across the intervening acres of countryside. Even if Bacon possessed a steed to rival Roland, he could hardly have made the journey in reasonable time, and if, as seems more likely, his mount was merely a cantering cob, the story becomes wholly implausible. It also ignores the question of how the busy cleric communicated with his other parishes. Whether the anecdote originated with Bacon himself, or one of his parishioners, is unclear, but it has all the hallmarks of a classic after-dinner yarn and is best enjoyed on that level.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist