Blog

30 June 2022

William Sancroft (1617-1693) was only quite briefly Master of Emmanuel, but he has left a remarkable legacy in the College. And as one among our Masters who found himself a player at a key turning point in British history, it is fitting that the College now has a number of portraits of Sancroft, although several of these have come by gifts and bequests in modern times.

Sancroft’s life spanned the turbulent years of the English Civil War, the reigns of Charles II, James II, and the accession of William and Mary. From a Suffolk family, Sancroft was admitted to Emmanuel in 1633 and elected a Fellow in 1642. As an ardent royalist, Sancroft spent the years 1657-1660 in self-imposed exile abroad in the Netherlands and Italy. The College’s portraits of a youthful Sancroft and his sister Alice probably date from 1650.

Above Left and Right; William Sancroft and Alice Sancroft, attributed to Bernard Lens. They wear mourning, possibly for their father and/or for the martyred Charles I. Sancroft wears a mourning ring and holds a Hebrew text open at Psalms 20 and 21: ‘The Lord hear thee in the day of trouble’ and ‘The King shall rejoice in thy strength’. Formerly at Gawdy Hall, Suffolk. Presented in 1957 by Mrs Mary Keith, a collateral descendant of Sancroft.

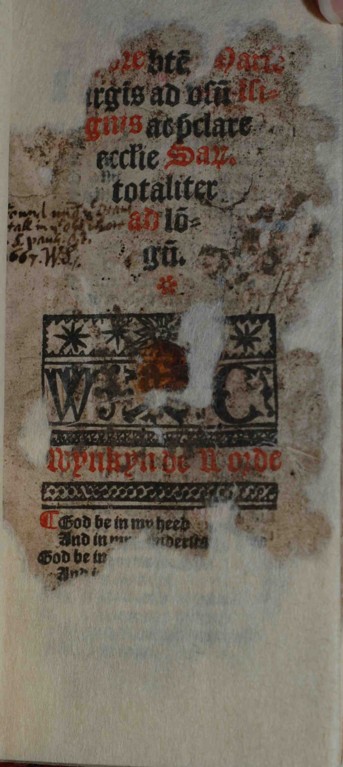

On the accession of Charles II Sancroft returned to England. Enjoying the King’s favour, Sancroft was successively Master of Emmanuel (1662-64), Dean of St Paul’s (1664-77), and Archbishop of Canterbury (1677-90). At Emmanuel, Sancroft commissioned the building of the chapel by Christopher Wren and set about turning the Puritans’ chapel into a library (now the Old Library). At St Paul’s, he initiated the rebuilding after the Great Fire of London – the College Library has the charred remains of a sixteenth-century book of hours that Sancroft found under the Dean’s stall in the the medieval Old St Paul’s after the Great Fire.

Above; Remains of a mouse-eaten book of hours that was printed by Wynkyn de Worde in 1521 and survived the Great Fire of London.

An enormous posthumous portrait – based on a contemporary sketch – now hangs in the Old Library and reflects the reputation Sancroft would acquire from his reluctant participation in a major constitutional crisis.

Above; Sancroft as Archbishop; on the table is a paper addressed ‘To the King’ (i.e. his petition against the Declaration of Indulgence’). By Peter Paul Lens, 1754; apparently commissioned by the College.

In 1685 Sancroft visited Charles II on his deathbed, speaking to that Merry Monarch with great freedom, which he said was necessary, since the King was going to be judged by One who was no respecter of persons. Sancroft then duly officiated at the coronation of Charles’ brother, James II, but the new King’s pro-Catholic agenda provoked increasing tensions. In 1688, Sancroft and other bishops petitioned the King against Anglican clergy being required to read out James’ Declaration of Indulgence, which suspended religious and civil restrictions against Roman Catholics and Protestant Dissenters. The point was that, since Parliament had approved these restrictions, the King’s actions were unconstitutional. Sancroft was imprisoned in the Tower of London with six other bishops, brought to trial for seditious libel, and acquitted. The universal rejoicing that greeted the bishops’ acquittal was a potent signal of public repudiation of the King’s policies. The Seven Bishops became popular heroes, and the episode fatally undermined James II’s authority. Medals were struck showing the bishops to commemorate this event, and the College’s group portrait is another example of such memorabilia.

Above; The Seven Bishops in medallions (Sancroft at the top) suspended on the columns of a temple-like structure; the columns are inscribed with the words ‘Columns of Truth’. Behind, an altar with seven candlesticks and tablets with Hebrew inscriptions. Above is inscribed Revelation 21: 3 and below Revelation 3: 12. By an unknown artist.

Bequeathed in 2007 by Mr Bryan Hall, historian of all things Norfolk and Suffolk.

But for Sancroft, the accession of William and Mary in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 brought not relief but further challenges. Having sworn allegiance to James II, and having anointed and crowned him, Sancroft did not believe himself free, in conscience, to transfer his allegiance to James’ daughter Mary and his son-in-law (and nephew) William. Refusing to recognize William and Mary as co-sovereigns, and withdrawing from public life, Sancroft was suspended from office (August 1689), then deprived (February 1690), and eventually expelled with his possessions and books from Lambeth Palace, retiring to his family home at Fressingfield in Suffolk. Here he devoted himself to his books and died praying ‘with great zeal and affection’ for the restoration of James II. The inscription on his tomb in Fressingfield churchyard, composed by himself, expresses absolute resignation to the divine will.

Historians from his own times onward have criticized Sancroft as timorously indecisive and ineffectual at a crucial juncture in English constitutional history. Yet it is hard not to sympathize with his dilemma: William and Mary would guarantee the established religious settlement, but Sancroft could not forsake his sworn loyalty to the legitimate king, even though, if James had not been ousted, Sancroft as chief prelate of the established church would have been on a collision course with the policies of a king who had already shown himself obstinately determined to advance his own agenda.

Shortly before his death, Sancroft gave his library to Emmanuel, rather than to Lambeth as previous seventeenth-century archbishops had done. This chance survival of his personal library – offers a unique opportunity to explore through his books the mind and intellect of a late seventeenth-century scholar, intellectual, and divine. It is twice the size of the library of the diarist Samuel Pepys preserved at Magdalene.

Although theology, church history and liturgical works account for over half the books, there are also classical authors, books on many aspects of history, natural sciences, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, law, travel, geography (including some fine atlases), and literature of all kinds, both classical and extensive samplings of French, Italian and Spanish literature, including plays. Included too are recusant devotional works, and printings of scripture in Anglo-Saxon, Irish and Malay. Books from other collections include some books from the library of the poet John Donne. There are sermons and tracts, but there are also books on demonology, magic and exorcism.

At their arrival in Emmanuel in 1693 Sancroft’s books more than doubled the existing holdings of the college library. Initially, Sancroft’s books were classified and shelved separately, but over succeeding years the Sancroft books were absorbed among the college’s other books. It was only in the 1970s that Sancroft’s library was reassembled as an entity, and shelved in its own room in cases that reinstate the earlier shelving of Sancroft’s books. Sancroft’s library is now one of Emmanuel’s great and most distinctive treasures.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

Helen Carron, College Librarian