Blog

23 March 2022

With war in Europe dominating the news, it is topical to look at how Emmanuel’s illustrated book collections depict military themes. Many of the books in the College’s Graham Watson Collection were produced during and after the quarter century of almost continual war that followed the French Revolution, so it is hardly surprising that military subjects are often the focus for illustration. But then, in the 1850s, and exploiting the technique of lithography, a pioneer war artist of genius would bring vivid images of the Crimean War to a wide audience.

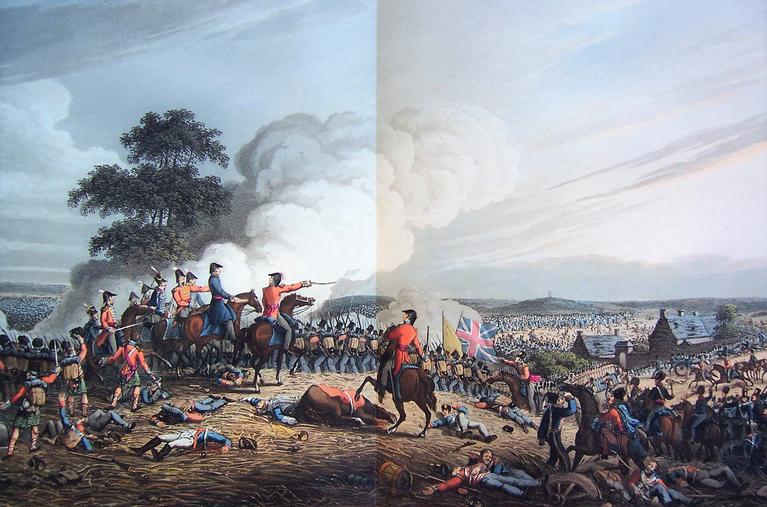

Victories of the Duke of Wellington (1819) commemorates each battle with a brief account and an illustration, and reflects the hero-worship of the ‘Iron Duke’ after the Anglo-Prussian defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo. Here are a group of Highlanders centre stage at the Battle of Vimiera (1808) during the Peninsular Wars. Vimiera was a hard-fought battle which, according to the accompanying text, cost the lives of three thousand French and one thousand British troops.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Pl 2: Victories of the Duke of Wellington (1819). ‘The Battle of Vimiera’; Pl 3: Historic, Military and Naval Anecdotes (1818). ‘’Boarding and Taking the American Ship Chesapeake (1813)’;

Historic, Military and Naval Anecdotes (1819) has a similar commemorative function, here recording the boarding and taking in 1813 of the American ship Chesapeake off Boston by HMS Shannon. According to the account it was all over with dispatch in the space of fifteen minutes, but with the loss of seventy American sailors.

Depictions of uniforms evidently had a great fascination to book-collectors at this period, judging by the splendid examples in the College’s collections, and most contemporary books about British costume and customs include examples of regimental uniforms as well.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Pl 4: Richard Cannon, Historical Record of the Eighteenth, or The Royal Irish Regiment of Foot (1848); Pl 5: William Henry Pyne, Microcosm (1806), ‘Army’;

So too William Pyne’s celebrated Microcosm (1806), which includes illustrations of military life alongside its depictions of the nitty gritty of contemporary crafts and trades. Here is a vivid scene of the wagons in a baggage train, characteristically focussing in on the practicalities of logistics. On the left a wagon is seen up close, with the soldiers’ partners and camp-followers, and piled with bedding. The text describes ‘a motley scene’, commenting sniffily on the ‘mixture of meanness and vulgarity in the manners and dresses of the women’. At the far left stands a soldier literally holding the baby. To the right the baggage train winds away into the distance.

Military Discoveries (1819) by Henry Alken, a prolific illustrator of comic books, zooms in on the absurd and ludicrous in contemporary military life. Here the key word is ‘Discoveries’, since each comic plate is explained by a rather lengthy caption that turns on the word ‘DISCOVER’. Here in the first plate is the comedy of anyone caught without their clothes – perhaps especially if they are brandishing swords at the same time (and note the worried female face peering from the tent). The caption reads: ‘Being awoken by a violent noise, and rushing from your quarters, you DISCOVER your Colonel, who commands you immediately to resist a serious and unexpected attack made on the Camp by the Enemy, without waiting for any additional Cloathes’.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Pl 6: Henry Alken, Military Discoveries (1819); Pl 7: Military Discoveries;

The second caption reads: ‘On recovery from a swoon, you DISCOVER it was occasioned by your horse being shot under you, and in the fall broke your Leg; on looking round you see both friend and foe leaving you in the lurch, that your only company are a pack of low-bred things who have actually had the honour to be killed by sword or bullet, while you have happened of nothing more than a commonplace accident’.

William Simpson (1823-1899) was a Scottish artist who recorded the Crimean War. Simpson was in the Crimea for a year, 1854-5, during the siege of Sebastopol, sending back his water-colours to London to be turned into lithographs, later collected in two large volumes of eighty plates, The Seat of War in the East (1855-6).

Here is Sebastopol seen from the deck of HMS Sidon, which was involved in blockading the port.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Pl 8: William Simpson, The Seat of War in the East, ‘Sebastopol from the Sea’; Pl 9: Seat of War, ‘Interior of the Malenkoff in Sebastopol after its Storming’;

Sebastopol was eventually taken, and this plate shows the interior of Fort Malakoff in the city after it was stormed.

Simpson’s illustrations provide a vivid picture of the lives of those manning batteries and fortifications. Here is ‘A Quiet Day in the Diamond Battery’ manned by sailors from HMS Diamond. The sandbags used for such enclosures are carefully depicted.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Pl 10: Seat of War, ‘Quiet Day in the Diamond Battery’; Pl 11: Seat of War, ‘Hot Day in the Batteries’;

By contrast here is ‘A Hot Day in the Batteries’ with men loading and firing the guns. Shells are bursting in all directions and the smoke of answering Russian fire is visible.

Simpson also memorably catches the mens’ lives by night. In ‘A Quiet Night in the Batteries’ some men are shown sleeping, while others chat in the light of a full moon.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Pl 12: Seat of War, ‘Quiet Night in the Batteries’; Pl 13: Seat of War, ‘Hot Night in the Batteries’;

But in ‘A Hot Night in the Batteries’ all is frantic action: guns are shown being fired or prepared for firing, and the night sky is lit up by explosions.

When the Russian forces abandoned the city of Sebastopol they set buildings ablaze, including, as shown here, the Public Library.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Pl 14: Seat of War, ‘Public Library, Sebastopol’; Pl 15: Seat of War: ‘A Ward in the Barrack Hospital at Scutari'

Today the Crimean War is perhaps most remembered because of the landmark achievements of Florence Nightingale in organizing the professionalization of nursing care for the wounded. Here she is shown in a ward of the Barrack Hospital at Scutari, where, as the text notes ‘the rough soldier in his untaught but noble chivalry kissed her shadow on the wall as she passed along’.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)