Blog

27 January 2022

Among the hand-coloured books in Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection are a number purporting to illustrate the costumes and customs of earliest times. The Costume of the Original Inhabitants of the British Islands, by Samuel Rush Meyrick and Charles Hamilton Smith (1810), takes the story back to even earlier times than Hamilton Smith’s Selections of the Ancient Costume of Great Britain and Ireland (1814). The illustrations in both books are – by the standards of the time – carefully-researched reconstructions informed by archaeological discoveries, early written sources, and the authors’ sketches copied from manuscript illuminations, seals, coins and tomb effigies.

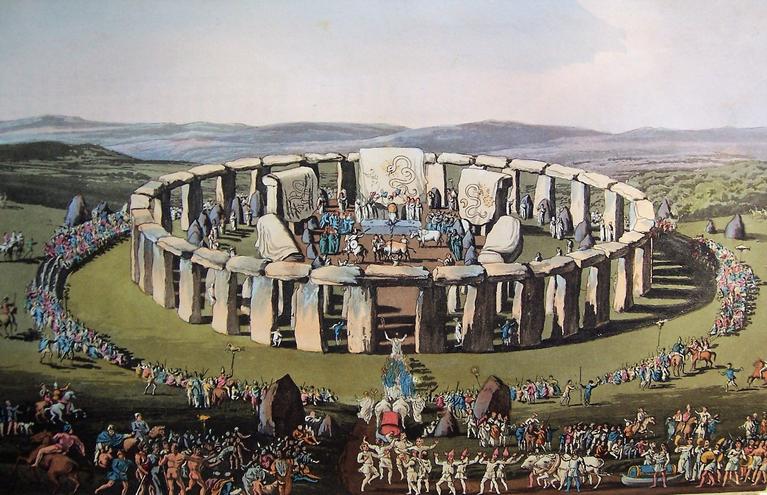

The striking reconstruction of the ‘Festival of the Britons’ at Stonehenge shows in the innermost enclosure the Druids honouring the sun god. Cattle are ready for sacrifice and the standing stones bear hangings depicting dragons. Outside the stone circle are gathered a general assembly of the people, who were never allowed within the sacred circle, or so it was believed. The accompanying text is a farrago of speculative imaginings about the ritual purposes of these still-mysterious stones.

Pl. 2: Original Inhabitants: Fishing;

A plate illustrating the ancient Britons’ pursuit of agriculture and fisheries depicts our predecessors in a park-like landscape arranged according to a distinctly Picturesque aesthetic, where the naked Britons are employing corracles to fish from.

Pl. 3: Original Inhabitants: An Arch-Druid in his Judicial Habit;

An illustration of an Arch-Druid shows him with various accoutrements and utensils based on items recently excavated in Ireland, including a breast-plate that, according to legend, had the power to squeeze the neck of the wearer who uttered a false judgement. Bottom right, the pet holy snake is helping itself to a holy beverage.

Depiction of the earliest British costume are derived from accounts by Julius Caesar and other Roman witnesses of how the inhabitants of the interior parts of Britain were clothed and armed.

.JPG)

Pl. 4: Original Inhabitants: An Ancient Briton of the Interior; Pl. 5: Original Inhabitants: Caledonians;

So here one ancient Briton is clad in ‘the skin of a brindled or spotted cow’, and carries spear, axe and shield. In the background is an earthwork fortification and at his side is what the text calls ‘his faithful dog, not only the trusty guardian of his hut, but his fierce and steady companion in war’. Roman writers recorded that inhabitants of ‘North Britain’ went about almost naked, sporting abundant tattoos. Depicted here are a pair of tattooed ‘Caledonians’ strolling starkers, but if you’re wondering about those less-than-balmy Highland temperatures, not to mention midges, the text says they are inspecting a cromlech in Cornwall. Everyone deserves a holiday.

.JPG)

Pl. 6: Original Inhabitants: Queen Boadicea; Pl. 7: Original Inhabitants: Anglo-Saxon Women, 750 AD;

The attire of Queen Boadicea – Boudicca, queen of the Iceni people in Norfolk, who led a revolt against Roman rule – is reconstructed from images of Celtic women on the columns of Trajan and Antonine. From other early accounts derive the patterned weave of her dress, the bracelets and rings, and that she was ‘a handsome woman but of stern countenance’. The twin breastplates at the foot of the page record those that had recently been ploughed up in a Somerset field. Among various warlike depictions of much later Anglo-Saxon kings and warriors are several plates recording the dress of Anglo-Saxon women, as here of around 750 AD. Both are dressed in long loose gowns, with long sleeves, and with a linen undergarment; over the head is a hood. One is shown spinning or winding from a bobbin; the other is mounted side-saddle.

Hamilton Smith’s Ancient Costume focusses more on the post-Conquest period and literally gallops through the medieval centuries with more splendid depictions of galloping and charging knights in armour than can be included here.

.JPG)

Pl. 8: Smith, Ancient Costume: Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, 1314; Pl. 9: Ancient Costume: Arthur MacMurroch, King of Leinster, 1399;

This plate of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster – dated to 1314 – must stand to represent the others, as he charges forward: indeed, the man is almost as magnificently turned out as his horse. The text explains that the image has been reconstructed from the Earl’s seal, including the emblazoned surcoat, and the dragon crest on the helmet and the horse’s head. Rather different is the depiction of Arthur MacMurroch, King of Leinster, who twice led resistance to Richard II’s incursions into Ireland in the 1390s. He is shown riding barefoot and without saddle, on a horse for which he reputedly traded four hundred cows – a dynamic image of resistance.

For the later medieval centuries the antiquarian authors could find so much more visual evidence to embolden them to reconstruct portraits of historic figures.

.JPG)

Pl. 10: Ancient Costume: Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland, and Joan Beaufort, 1425; Pl. 11: Ancient Costume: Queen Margaret of Anjou;

This double portrait, dated to 1425, attempts to retrieve the costume and likeness of the powerful Northern magnate Ralph Neville and his redoubtable wife Joan Beaufort, daughter of John of Gaunt, who was visited by the early autobiographer Margery Kempe. The splendid armour and lavish dress are copied from the couple’s alabaster effigies. A similarly lavishly-dressed portrait of Margaret of Anjou (formidable consort of the hapless Henry VI), dressed in cloth of gold and with a pearl-edged headdress, is derived from a tapestry.

But other plates are alive to the class distinctions that were inseparable from clothes.

.JPG)

Pl. 12: Ancient Costume: ‘A Sportsman of Rank and Gamekeeper’; Pl. 13: S. R. Meyrick, A Critical Enquiry into Antient Armour (1824): Black Armour;

Here a young sportsman wears a very smart scarlet jacket with the fashionably puffed sleeves that were so much in vogue in the first half of the fifteenth century; he wears black hose, and his modish bonnet has flown off and is in the foreground. Meanwhile his gamekeeper is dressed in an altogether more subdued and serviceable way. Not for him the stylish black armour that was the last word in ostentation by the early sixteenth century.

These books derive from a kind of archaeological impetus to help readers visualize past British costume and custom on the evidence of surviving material culture. Other illustrators might be more light-hearted. Among the many theories advanced to explain the purpose of the standing stones at Stonehenge, the idea that they are the stumps and bails in a form of Druid cricket has not received the attention it deserves. Here, in The Comic History of England (1848), an understandably worried-looking Druid has been put in to bat against Father Time.

Pl. 14. Gilbert Abbot A’Beckett, The Comic History of England (1847-8), ‘Time Bowling Out The Druids’

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)