Blog

25 February 2021

Books on sporting subjects feature largely among the late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century hand-coloured books in Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection, and these can be very revealing of contemporary attitudes. Henry Alken’s The National Sports of Great Britain (1823) is a lavish production with many fine plates. Like so many other colour-plate books of this period it is now exceptionally rare, because the large plates were so temptingly suitable to cut out and frame.

In common with other books of this period about sporting subjects, Alken’s definition of ‘sports’ is of course very different from our own. Apart from horse-racing and prize-fighting (a bare-knuckle forerunner of boxing), ‘sports’ for Alken consist largely of the quintessentially rural pastimes of field sports – hunting, shooting and fishing. Written two centuries ago, the text accompanying the plates can hardly be expected to conform to modern preoccupations about cruelty to animals. As a keen practitioner of field sports himself, Alken celebrates these as part of the cultural traditions of the countryside. Yet the text also repeatedly and passionately criticises what it sees as gratuitous cruelty to animals, which forms no part of its concept of sportsmanship.

Some ‘National Sports of Great Britain’, such as hawking and falconry, are evidently included out of an ambition to produce a comprehensive historical record, since the text acknowledges thankfully that this cruel sport is now obsolete, ‘irrevocably doomed to oblivion in this country – a doom which no Sportsman ought to regret, considering the cruelties with which it was attended, in training, and in feeding the hawks upon living birds and animals’. (Alken’s plate on hawking is the only one in the book to show a woman pursuing a sport). Also illustrated with a plate is the hideous pastime of ‘drawing the badger’ – essentially the repeated worrying of a captive badger by dogs – and the text comments on the unpleasant expressions of the human perpetrators and exclaims about the badger: ‘thus he suffers, until the beastly inclinations or cupidity of his torturers and murderers are satiated!’

Plate 1. Henry Alken, National Sports of Great Britain (1823), ‘The Race’;

Alken’s National Sports pairs together horse-racing and prize-fighting as the most characteristically English sports, which boast equally long pedigrees. One plate is at least as interesting for showing the human beings at a horse race, with crowds of top-hatted men near the course (no rails at this date), but with ladies watching from behind, some from carriages (Plate 1). Here horse-racing is flat racing, and at this point it is illuminating to include as well Emmanuel’s copy of Alken’s study of The Steeple Chase of 1827 (now a very rare book indeed), where our hero (the rider in all-white colours) wins the race for his patron (Plate 2).

Plate 2. Henry Alken, The Steeple Chase (1827), ‘Crossing a deep ravine, dangerous to pass … With 6 to 2 on White’;

The cruelties of horse-racing are also fully discussed, but with some sense that bad old ways had been gradually abandoned during the previous century. The text sees the strongest objection to horse-racing as that excessive use of a whip that is still questioned to this day: ‘since whipping and spurring with the utmost strength and power of the jockeys has been immemorially the custom, with or without reason or necessity … Even the ladies upon the stand have been accustomed to look upon such a disgusting spectacle, at least without reprobation’. If we now think the writer is too sanguine (‘many or most of the barbarities of the old English Turf, like goblins and ghosts, have vanished before the light of modern humanity and sense of justice’), we should bear in mind that he is comparing with a time not long before when flat races could resemble mounted brawls, with jockeys accustomed to fight while on horse-back during the race, striking both each other and their rivals’ horses with their whips. Such is the writer’s respect for horses that it is in the context of racing that he acknowledges a contemporary shift in his day towards thinking not only that it is right to treat animals fairly, but even that animals have a moral right to expect to be so treated – though he admits sadly that some detractors sneered at any such notion of what they ridiculed as ‘the rights of cattle’.

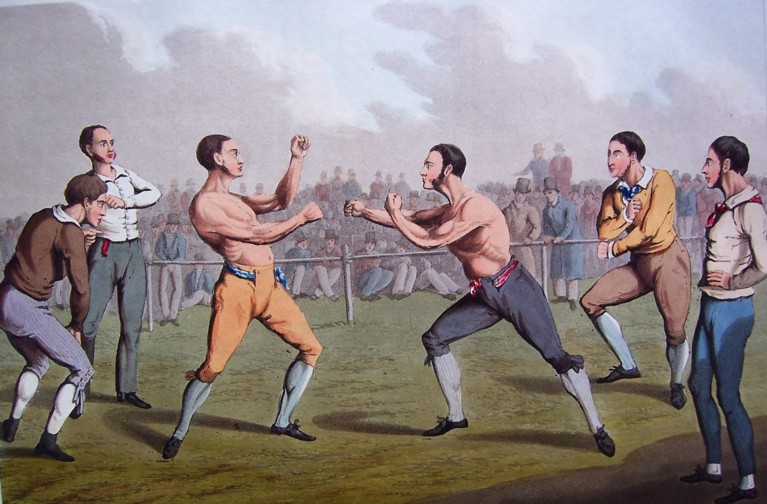

Plate 3. National Sports, ‘Prize-Fighting’;

No such issues affect the text’s glowing account of prize-fighting, which it terms a scientific system of ‘pugilism’ peculiar to England and with beneficial moral and social effects (Plate 3). This is because ‘it has not only afforded a vent for the human passions in a milder form, but it has impressed a superior character on the lower orders of Englishmen’. All the customs and observances of the match – the appointment of umpires and seconds, the opponents’ shaking hands beforehand ‘as much as to say, we mean to contend fairly and like men’, the spectators’ concern to see a fair fight without fouling and with fair treatment for the loser – serve to form ‘so excellent a practical system of ethics as no other country can boast, and has chiefly contributed to form the characteristic humanity of the English nation’.

Plate 4. National Sports, ‘Stag Hunting’; Plate 5. National Sports, ‘A Highland Hunt’;

At the time Alken’s Sports illustrated it, stag-hunting had evidently been in decline Plate 4). The text only knows of two packs of stag-hounds in England apart from the one at Windsor, where George III had enjoyed stag-hunting – although at Windsor stag-hunts usually ended with the stag being captured and returned to its habitat rather than killed. In Scotland at this time there were attempts – in what now seems a Romantic and nostalgic spirit – to hold hunt meetings in conscious imitation of what were believed to have been the splendours of ancient hunting in the Highlands. Alken’s plate is evidently a Romantic imagining of the end of such a day’s hunt, which to contemporary English eyes was unusual in mixing hunting and shooting (Plate 5).

Plate 6. Samuel Alken, Delineations of British Sports (1822), ‘Fox Hunting’;

There is a similar enthusiasm for all the rituals of fox-hunting, which unlike stag-hunting is flourishing and also invested with a unique cultural significance: ‘the Charms of the Chase have, in this country, an almost universal influence, even to fascination … They form one of our grand national lyrical subjects …’ and this fascination is felt from noblemen, squires and parsons to ‘country labourer and mechanic … a hunt is everything’. Here, in a contrasting style, it is illuminating to introduce one of the plates in our very rare copy of Delineations of British Sports (1822) by Samuel Alken, Henry Alken’s brother (Plate 6). Mr Fox is scooting from the hounds towards a gap in the fence to some woodland, where he might soon be pursued by the huntsmen in the distance. But a notice by the fence to the wood reads ‘MEN TRAPS!’

Plate 7. National Sports, ‘Pheasant Shooting’; Plate 7B. Delineations, ‘Shooting Water Fowl’; Plate 8. Delineations, ‘Trout Fishing’;

Both Henry and Samuel Alken have many plates depicting various kinds of shooting and fishing, many being pursued while exceptionally well-dressed in a distinctly gentlemanly fashion (Plates, 7, 7B, 8). But the commentary to one of Henry’s depictions of fishing again distances itself from any avoidable cruelty: ‘we shudder at and abominate the use of living baits; and never, with quiet feelings, tear the hook from the gorge of the captive fish …’

Plate 9. National Sports, ‘Bear-Baiting’;

Also depicted as national sports are the (to us unspeakable) practices of ‘baiting’ or tormenting captive bears and bulls with dogs. The text notes that bear-baiting now rarely happens and ‘is attended only by the lowest and most despicable part of the people’ (Plate 9). In this, it sees some historical progress, recalling that Queens Mary I and Elizabeth I both delighted ‘in viewing these barbarous and bloody spectacles’. The text notes the role of some contemporary clergy, peers and MPs in denouncing animal cruelty, while contrasting a sixteenth-century commentator who observed that ‘If there be a bear or a bull to be baited in the afternoon, the minister hurries the service over in a shameful manner, in order to be present at the show’, and quotes from the seventeenth-century diarist John Evelyn on how an important bill failed to pass in the Commons because members were elsewhere to see a tiger baited by dogs.

Plate 10. National Sports, ‘Bull-Baiting’; Plate 11. National Sports, ‘Bull-Baiting’;

Alken’s two bull-baiting plates do at least depict the bull getting its own back in goring and hurling away the tormenting dogs (Plates 10, 11). According to the commentary, bull-baiting in England originated in the reign of King John in Stamford in Lincolnshire. The text notes that modern clergy ‘have stood forth to explain the wickedness and infamy of this unnatural and pseudo-diversion [and] the press has taken the part of outraged humanity’. Warming to its theme, the text complains passionately ‘It is utterly unlawful and absurd, or rather insane, to worry out the life of an animal, by slow and horrid tortures, merely because nature has bestowed upon it fierceness and courage. What then must be the dire infatuation of one animal, and that animal pretending to rationality, deriving pleasure and sport from the outraged feelings and tortures of another! – Man, man, complain no more of the injuries and cruelty inflicted upon thyself!’ The failure of Parliament to legislate adequately is lamented, and the bull-fights of Spain and Portugal are duly branded ‘equally atrocious, but far more dangerous and manly than English bull-baits’

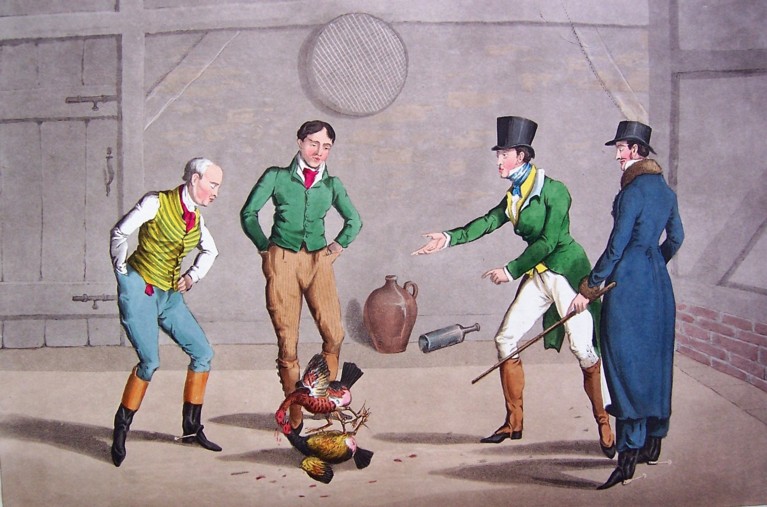

Plate 12. National Sports, ‘Cock-Fighting’;

The enjoyment of cock-fighting, however, is regarded as a different matter, while admitting that ‘This sport has been constantly decried as cruel and immoral by those writers who laudably advocate a due consideration for the feelings of brute animals’ (Plate 12). The distinction from watching animal baiting in this writer’s mind is that only a special breed of cocks is good for cock-fighting, and these birds are instinctively and violently pugnacious with each other. But if it so happens that they won’t fight, no human being can make them do so. So cock-fighting, the argument goes, is ‘void of that cruelty that attends baiting …consisting of the more arbitrary and capricious infliction of torture, which are unmanly, infamous, and detestable, whereas to witness the spectacle of a cock-fight is a legitimate object of curiosity, in which we admire, in their voluntary combats, the fierce courage of these feathered animals …’

Plate 13. National Sports, ‘Owling’;

The number of plates in National Sports allows Alken to include such quaint and quirky activities as ‘Owling’ (Plate 13). Since any owl that appears in the open in daylight will tend to be mobbed by other birds, the trick was to allow a trained owl on a string to fly to and fro, thus attracting pigeons and other birds that will alight on the limed surfaces of what look to us rather like telegraph-poles, and so be caught for the pot.

Plate 14. Delineations, ‘Poaching for Rabbits’.

And the final plate in Samuel Alken’s Delineations acknowledges that there is another, illicit, kind of hunting (Plate 14). The plate depicts some poachers taking rabbits, and since Alken shows the next field positively teeming with rabbits, there appear to be enough for everyone.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)