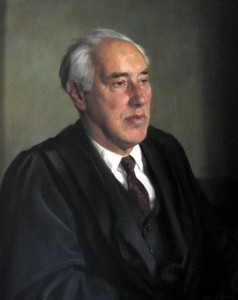

Edward Welbourne (1894 - 1966)

Historian and immensely influential 20th Master of Emmanuel during the 1950s and early 1960s

'If you put two Emmanuel men together they will talk happily of Welbourne.' That must be true of most Emmanuel men now alive, whether they knew Welbourne as undergraduate, Fellow, tutor, history supervisor, or Master. He came to the College in 1912 as a scholar, from a country grammar school which he described as incredibly incompetent, but where one of his formally quite unqualified masters was a genius as a teacher and shared with his pupil his own diligent desire to learn. He took a double first in history and rowed in a Lent boat before being whisked away to war service in France, where he suffered leg wounds which could still trouble him forty years after, and where he earned a Military Cross. But when Emmanuel men remember Welbourne they think of him primarily as a great talker. The flow was prodigious; and though the sequence of ideas was sometimes too rapid for ordinary mortals ('Why are there so few Roman Catholics in East Anglia? Because it's so flat' - see note 1) it was a discerning man who claimed that his education was effected while he was getting an ‘exeat’ from Welbourne.

His subject was, formally speaking, economic history; his 1921 dissertation on the Durham and Northumberland miners' unions (published in 1923) had won at a blow the Thirlwall Prize, the Seeley Medal, and the Gladstone Prize, and set him on the path of history teaching in the University. When asked why he wrote so little thereafter - or rather published so little, for his correspondence was as voluminous, as forceful, and as startling as his talk - he replied that he had been more interested in reading what others wanted him to believe they thought than in trying to persuade them that he meant nothing other than what he said.

Welbourne was a Lincolnshire man, the son of a police officer, brought up in a country environment of common sense and sound human values. His prejudices were more tempered by compassion than his hearers sometimes thought; for when he found people blind to one half of the truth he would exaggerate that half, simply to show up their blind spots. His real indignation was against humbug and pretentious ignorance, against the muddled thinking of mistaking the label for the reality. The thirteen years of his mastership were a time of much repair and rebuilding in Emmanuel, and of the planning and fund-raising for the new South Court; but his concern for the College was always primarily in terms of people. As admissions tutor he had a flair for spotting the promising boy. If he occasionally acted without the Fellows' knowledge, he said, it was not without their consent. Emmanuel men will talk of him for many years yet.

[Note 1: Hence few railway cuttings, and therefore little immigrant Irish labour.]