Blog

24 June 2020

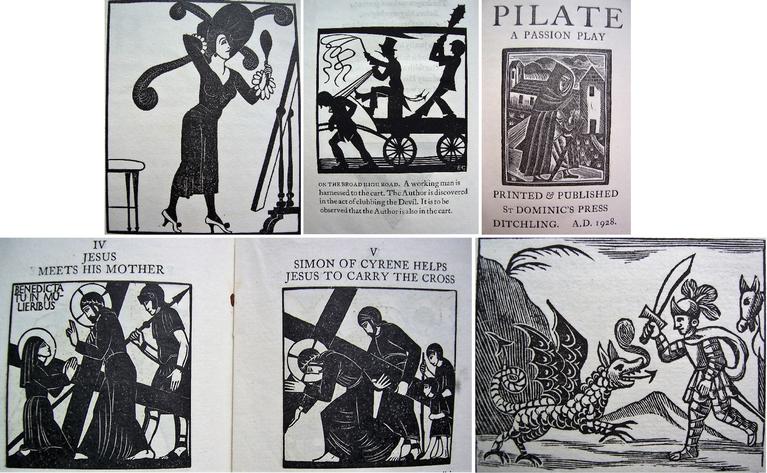

As a result of the donation of the Chapman Collection of twentieth-century material, Emmanuel Library has interesting items from Saint Dominic’s Press, which was founded in 1916 in the East Sussex village of Ditchling by Hilary Pepler (1878-1951), with Eric Gill (1882-1940) providing wood engravings. This press became part of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, an artists’ colony established at Ditchling in 1921 by Pepler, Gill and Desmond Chute (though Gill left the community in 1924). The Guild espoused a communal life and self-sufficiency, based around work and faith, and their idea of a medieval guild. Their core principles were a devout Roman Catholicism, resistance to industrialization and urbanization, and a commitment to Distributism, a political movement that championed individual land ownership in rural communities and whose contemporary proponents included G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc. The community had grown to 41 members by 1922 and eventually occupied a cluster of communal buildings, workshops, family homes and a chapel on the edge of Ditchling Common. The Guild was part of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and among the artists and craftsmen drawn to join were wood engravers, weavers, silversmiths, calligraphers, and artists and illustrators. A plaque produced in the community bears the self-description ‘Men rich in virtue studying beautifulness living in peace in their houses’. Men? Yes, there were no women members until the 1970s. The Guild was finally disbanded in 1989, and is now commemorated by a small museum at Ditchling.

Key to the community was its private press of Saint Domenic’s, which printed a variety of pamphlets and books, many on religious themes, or propounding the philosophies of the artists and their theories about craftsmanship, or the failings of modernity. A pamphlet entitled In Petra produced by Gill and Pepler in 1923 has some wood engravings by David Jones (1895-1974), and the verse that accompanies a woodcut by Jones of an aspidistra – the once-ubiquitous house-plant – perhaps can serve to catch the pietistic tone:

God made the Aspidistra,

A bold and bulbous weed,

To grace the ground of Eden

And flourish without seed.

When Man became respectable,

He stole it from the field

To hide his utter nakedness

Behind its leafy shield …

He had an Aspidistra,

Green in a marble bowl,

Brass candlesticks on either side –

By then he’d lost his soul …

So burn your Aspidistras,

And vase and candlesticks,

Return your lace to Nottingham,

And make a Crucifix.

Something of the same tone figures in Gill’s 1921 pamphlet Dress: Being an Essay in Masculine Vanity and an Exposure of the Un-Christian Apparel Favoured by Females (No 7 in the bracingly-entitled ‘Welfare Handbooks’ published by the Press), which includes a woodcut by Gill on the theme ‘She outshines the Peacock’s excess above his mate’, showing a woman admiring herself in a piece of millinery worthy of Royal Ascot. Another striking woodcut by Gill shows the Devil seated in a cart being drawn by a working man, while the artist strikes at the Devil from behind with a club so large that it breaks out of the frame of the picture.

Pepler had a contemporary reputation as the author of mimes, and when the Press published a Sussex Mummer’s Play, King George and the Turkish Knight: Old Sussex Play (1921) it was because this was seen as ‘genuine folk drama played by the peasantry’ that was ‘undoubtedly an offshoot’ of the miracle plays put on by medieval guilds. But this was heritage that was fast disappearing and had been taken down from someone who had last participated in a performance in a Sussex village in the early 1890s. The notes stress the play’s distance from any contemporary ideas of dramatic verisimilitude: the actors, forming a semi-circle, should each ‘march forward three paces to deliver his oration’, almost chanting their words in a monotonous sing-song with little or no expression. The Valiant Soldier can have a soldier’s red jacket, but ‘in modern representations the tunic would probably be in khaki’. The Turkish Knight is to have ‘black face and beard’ (oh dear …).

A tiny pamphlet Concerning Dragons (1916), by Pepler and Gill, is made for child-size hands. On the left-hand page of one opening, beneath a woodcut of a worried-looking child in bed, with an adult peeping through the bedroom door, is the rhyme:

CHILD:

When Michael’s angels fought

The dragon, was it caught?

Did it jump and roar?

Oh! Nurse, don’t shut the door.

And did it try to bite?

Nurse, don’t blow out the light.

NURSE:

Hush, thou knowest what I said,

Saints and dragons all are dead.

On the right-hand page, beneath a woodcut of a child holding a crucifix towards a very large devil with claws, is the rhyme:

FATHER (to himself)

O child, Nurse lies to thee,

For dragons thou shalt see.

And dragons shalt thou smite –

Let Nurse blow out the light!

Please God that on that day

Thou may’st a dragon slay.

And if thou dost not faint,

God shall not want a saint.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)

Back to All Blog Posts