Blog

26 March 2024

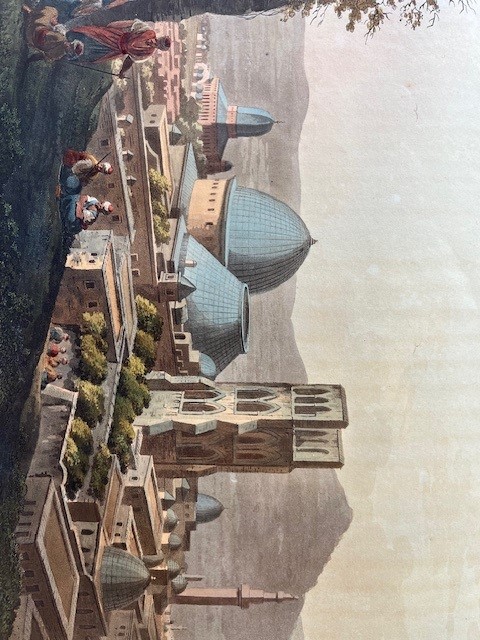

Mayer, ‘Views’: Jerusalem, with the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

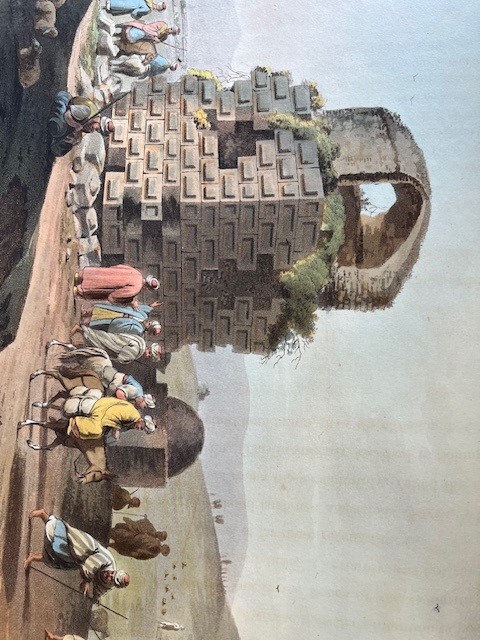

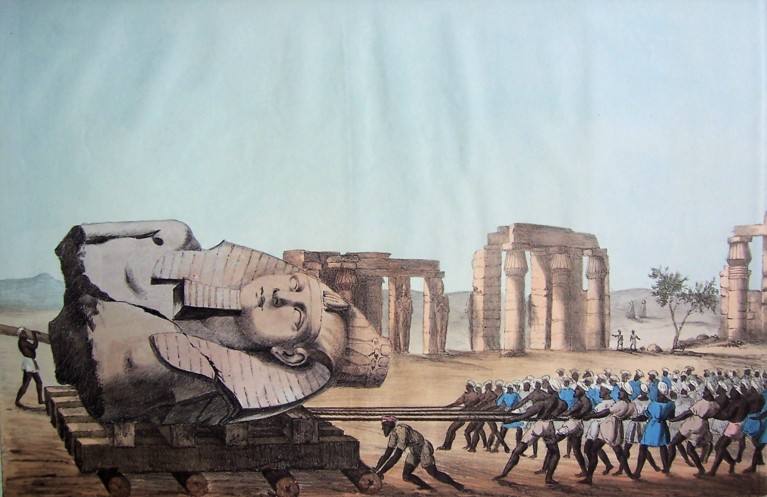

In Holy Week, thoughts turn to the Holy Land, and never more so than this year. Emmanuel’s collection of illustrated travel books from the late eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries contain only limited images of the area, which was just becoming an object of curiosity to more intrepid spirits, interested in travelling wider than Europe in search of the picturesque. The splendid exception is Views in Egypt, Palestine, and other parts of the Ottoman Empire (1804) by Luigi Mayer (1755-1803). Italian-born, of German ancestry, Mayer was commissioned by Sir Robert Ainslie Bt, British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire (1776-1792), to record landmarks and landscapes throughout the Ottoman possessions. (Ainslie presented Mayer’s original paintings to the British Museum).

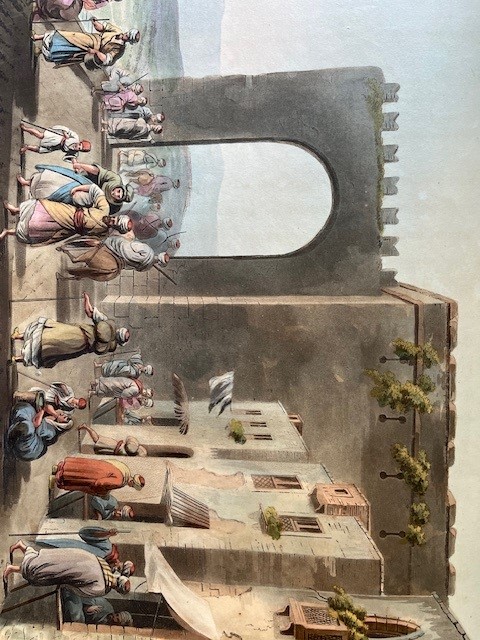

As the nineteenth century wore on, advances in communications and much improved opportunities for tourism resulted in an enormous increase in the numbers visiting the Holy Land. A special interest of Mayer’s ‘views’ is that they record some of the sites famous from Biblical accounts as they still were before this onslaught. Mayer presents the Holy Places in a picturesque dilapidation, as they had apparently remained during the long centuries of the Ottoman Empire’s decline.

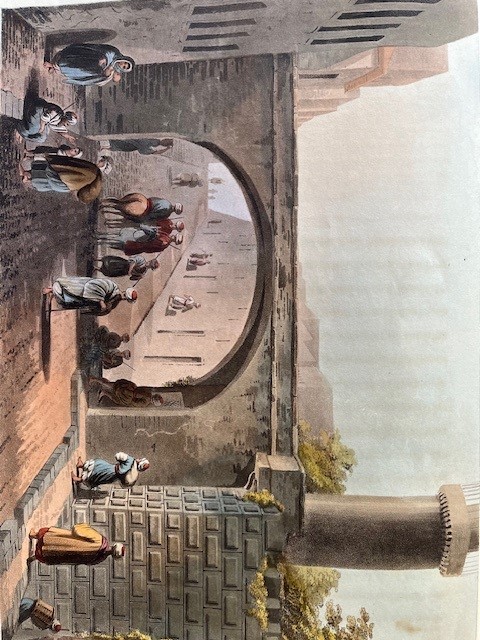

Mayer’s street scenes in Jerusalem can thus appeal to the age’s much wider taste for the melancholy inspired by the prospect of ruins, as well as recording the current state of places mentioned in the Bible’s narrative of events in Holy Week.

Pillar to which was affixed the sentence passed on Our Saviour

Remains of a Tower on Mount Zion

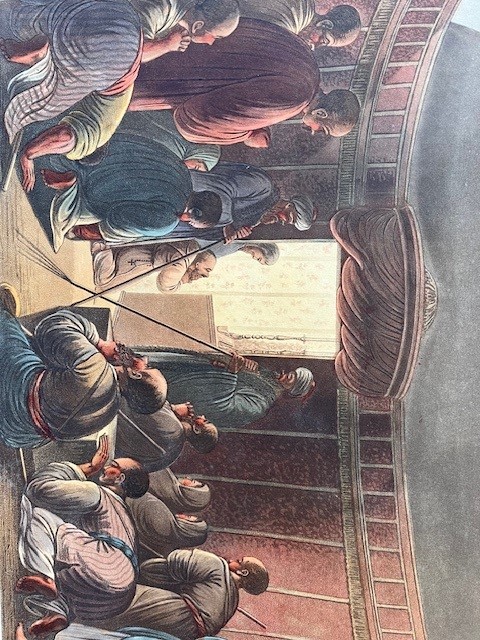

For Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem the most important site has always been the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built over the site of Christ’s crucifixion on Mount Calvary. Inside the Church, pilgrims visited the site of the cross and the sepulchre, as well as the places where, it was believed, Christ was nailed to the cross and where his body was later anointed by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus. Mayer’s views catch the gloom of these interiors, lit by candles.

Entrance of the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre

Tomb of Joseph of Arimathea

This is also so of the reputed sepulchre of the Virgin Mary near the Garden of Gethsemane, over which a church had been erected by St Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine. Pilgrims descended into the subterranean church to where the Virgin’s tomb stood in a chapel hewn out of the rock. Her tomb was venerated by local Muslims, who helped defray the cost of the eighteen lamps kept constantly burning in front of the Virgin’s tomb. Here, as in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, only the thresholds of the most sacred shrines are depicted.

Tomb of the Virgin Mary

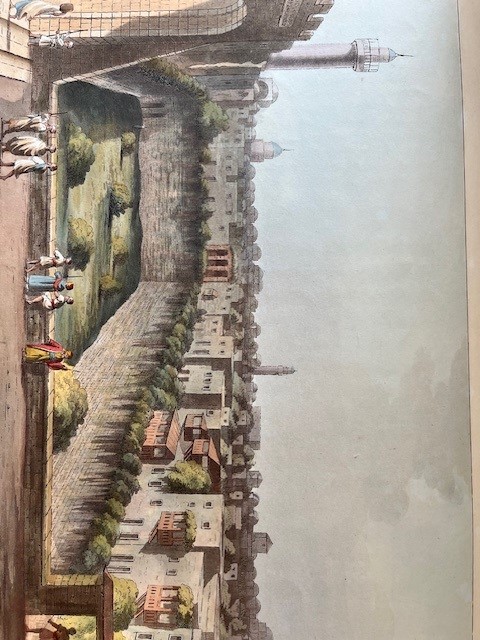

The Pool of Bethesda, Jerusalem

Much less frequented was the Pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem, where Jesus bid a paralysed man ‘Rise, take up thy bed and walk’ and so he did (John 5: 8-9). At what was believed to be the site in Mayer’s day any springs of water had dried up and the site was overgrown.

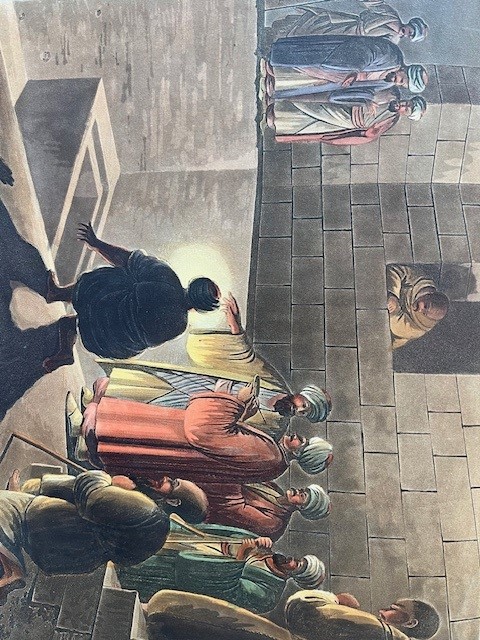

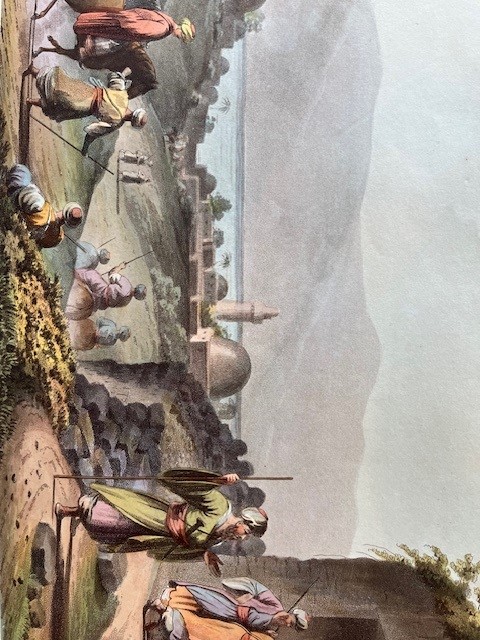

At Bethany was the home of the sisters Martha and Mary, whose brother Lazarus Christ raised from the dead after four days (John 11: 1-45), a miracle that prefigured his own resurrection. Mayer also illustrates some subterranean tombs at Bethany, by implication the site of the miracle.

The Village of Bethany and the Dead Sea

Sepulchral Chamber near Bethany

Also illustrated are scenes at Bethlehem, where a church had been built over the supposed site of Jesus’ birth. There was a subterranean chapel of the Nativity, with a further chamber exhibiting the manger, along with a handy shelf upon which the Three Wise Men were believed to have deposited their gifts. A nearby cave contained a vault ‘where they say’ were buried the Holy Innocents, the children murdered by Herod. Also to be seen was the grotto ‘in which they report’ St Jerome remained for fifty years – rather understandably since he twice translated the Bible into Latin there.

Principal Street of Bethlehem

Subterranean Church of Bethlehem

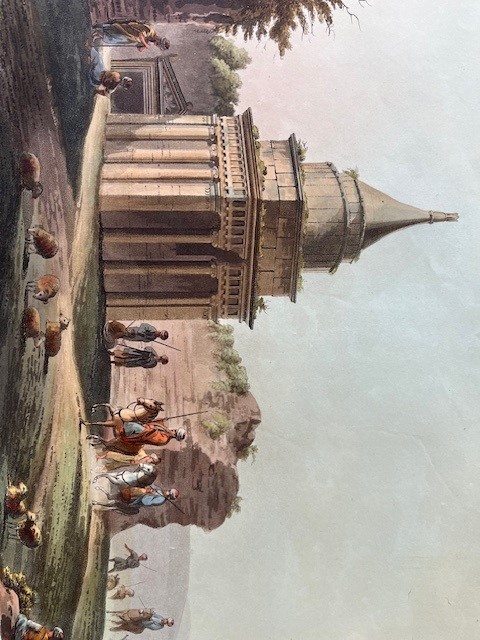

As Mayer travels around sketching and painting, he also records ruins, reputedly from Old Testament times, in states of picturesque decay, such as the tomb that Absolom had reportedly built for himself, or the supposed tomb of Rachel, the wife of Jacob, although in his accompanying commentary Mayer sniffs that she was certainly never buried in a building so relatively modern.

Sepulchre of Absolom

Sepulchre of Rachel

In Mayer’s record of the picturesque, stones are tumbled and vegetation sprouts from ruins. Outside, vistas recede, while in dim interiors gleam spots of light in a religious glow. It is an intriguing snapshot through western eyes of places familiar from the Old and New Testaments at the end of the eighteenth century.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

26 March 2024

As I write this blog entry, it is a beautiful Spring morning. The sun is shining and there is not a cloud in sight. The morning is fresh, but the sunlight lifts the soul. The apricity of the sun against your face seems to make a job in gardening worthwhile.

This has not, however, been the case for the whole month that has preceded it. We have been battling the cold, grey skies and the plentiful rain. It certainly has been a challenge. Hopefully the weather will start to improve with a spell of dry weather forecast.

In the College gardens we have been busy all the same. March has been the time for many of the seasonal tasks, including pruning the shrubs grown for their winter stems, hard pruning of the buddleias, mulching of the beds and keeping on top of the early growth of grass.

The team have also been busy repairing damaged areas around the swimming pool. The grounds had been messed up a little from the construction work to the pool. It was a good opportunity to put things right.

We replaced some of the wooden path edges, laid some additional paving and graded some topsoil ready for grass seeding. Finally, we top dressed the gravel paths to bring the project together. The pool still must be relined when the weather improves but the areas surrounding it at least now look neater.

Around the grounds, the spring bulbs are in full effect, the Paddock is being framed by the daffodils and the successional bulbs under the oriental plane tree in the Fellows' Garden look amazing.

The magnolia in the Jester Garden is looking its striking best at present.

It’s well worth a look before the magnificent pale, pink flowers drop due to a heavy frost or a stormy night.

Earlier this month, I was delighted to welcome former alumnus and celebrity gardener, Charles Dowding, back to the College. I had arranged for Charles to spend a day and an evening with us, passing on his vast experience of his now world famous ‘no-dig’ philosophy.

Charles gave us a masterclass practical demonstration in the afternoon and valuable advice on our existing compost systems. For the masterclass, we were joined by many of the other colleges' Garden Departments. It was great to share this experience with many in our university garden community.

In the evening, Charles gave a talk to a packed audience in the Queen's Building Lecture Theatre. It was great to be part of this event and the feedback from the audience was very well received.

I had the pleasure of dining with Charles at High Table in the evening and it was another chance to pick his brains. Altogether a fantastic experience for the Garden Department.

Best wishes.

Brendon Sims, Head Gardener

26 March 2024

A is for … Acorn

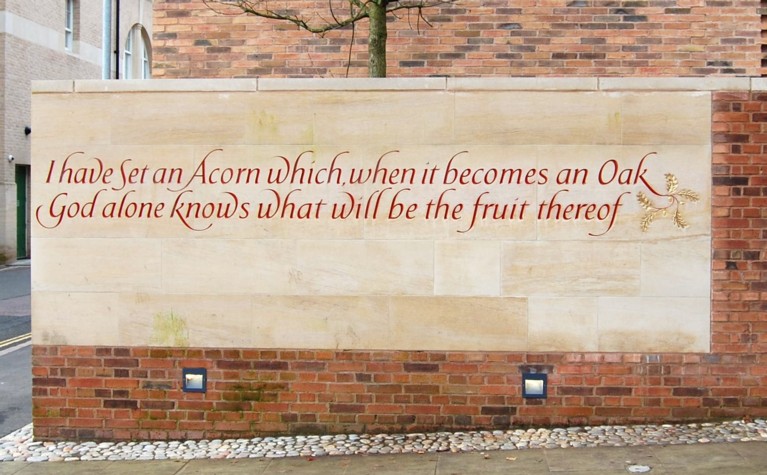

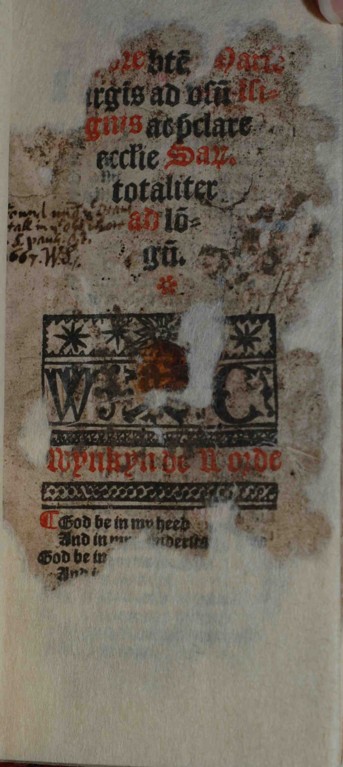

The Founder of Emmanuel, Sir Walter Mildmay, liked to talk of his college as an acorn, ‘which, when it becomes an oake, God alone knows what will be the fruit thereof’.

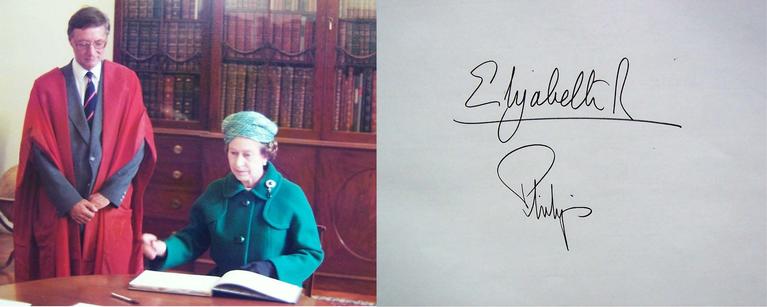

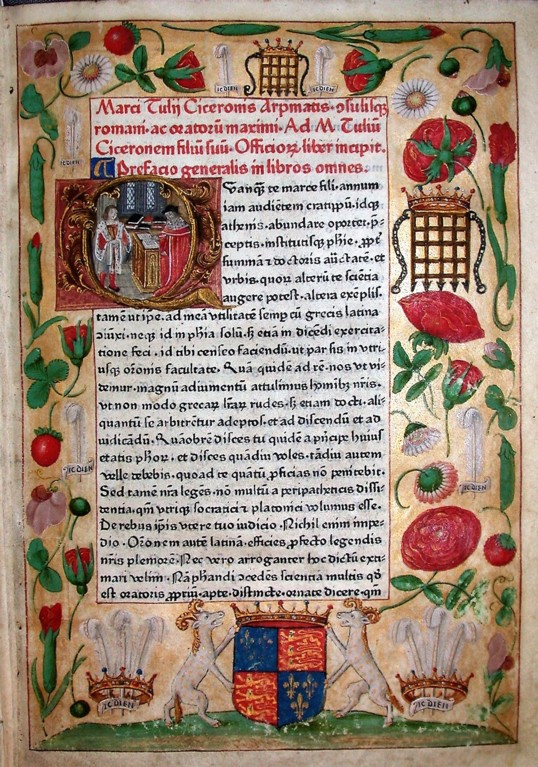

Quoting this remark many years later, William Dillingham, Master of Emmanuel 1653-62, added that Mildmay’s acorn had indeed grown into an oak, ‘whose topmost branch adorns and revives the primacy of our Church’. This was a reference to the elevation of William Sancroft, a graduate and former master of Emmanuel, to the office of Archbishop of Canterbury in 1677. Acorn imagery can be seen on the bindings of both the college’s original copy of the founding statutes, and on the Founder’s personal copy.

.jpg)

Acorn motifs have also been used in the college’s newest building, Young’s Court, which opened in the summer of 2023. A beautiful carving of Sir Walter’s ‘acorn’ remark can be seen on the wall adjoining the entrance to the court, while a transparent plaque inside Fiona’s, the new college café and Hub, displays an ingenious representation of an acorn, made up of the names of donors who supported the Young’s Court building appeal.

A is for … Apethorpe

Like most Tudor self-made men, Sir Walter Mildmay converted his wealth into real estate at the earliest opportunity, purchasing Apethorpe (pronounced ‘Appthorpe’) manor house in Northamptonshire in 1551.

Sir William Cecil owned a nearby estate, where he was later to erect the gargantuan Burghley House. It was undoubtedly serendipitous for Sir Walter to be such a close neighbour of Cecil, who was to serve as Elizabeth I’s principal minister for almost her entire reign. There was, nevertheless, genuine friendship between the two men, who shared a common religious and political outlook. Apethorpe remained in the hands of Mildmay’s descendants until 1904. The costs of upkeep forced its sale after the Second World War, and it became an educational establishment. The contents were sold off, and Emmanuel College was able to buy several pieces of furniture in 1948, including the ‘Founder’s table’, now in the gallery.

A year later the new owners of the Hall gave the college the inscribed tablet, topped with a roundel showing the Mildmay coat of arms, that Sir Walter had set up over the fireplace in the great hall in 1562. It now overlooks the main staircase in the college library.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

28 February 2024

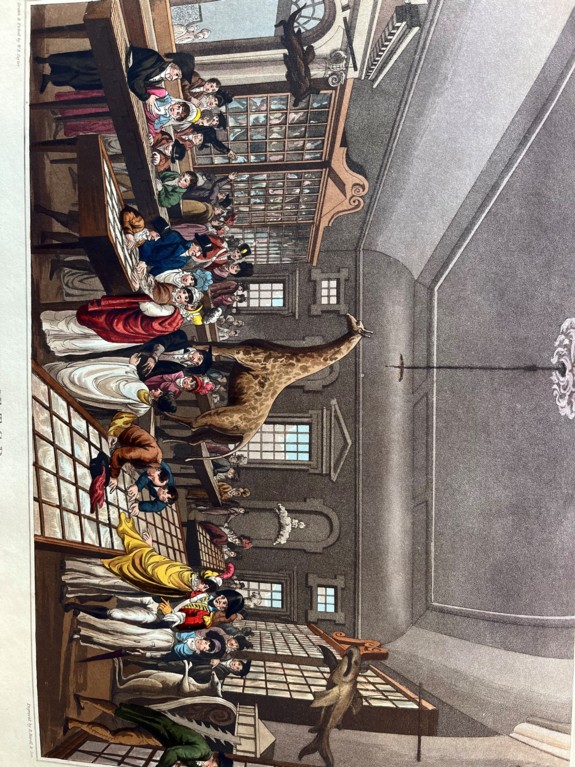

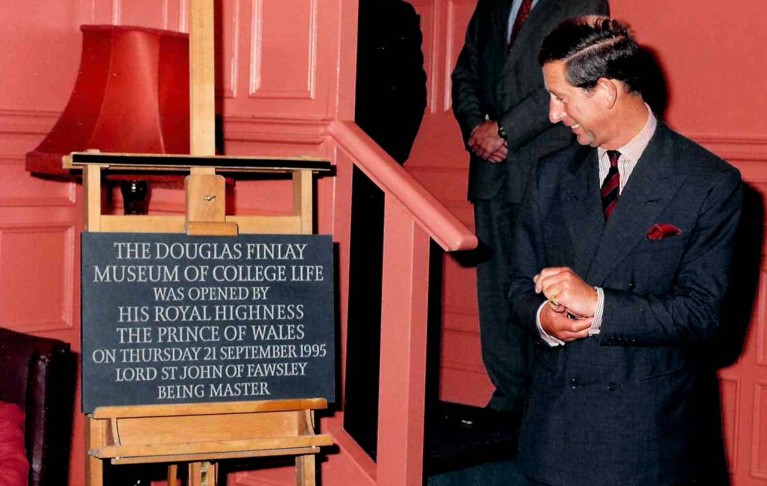

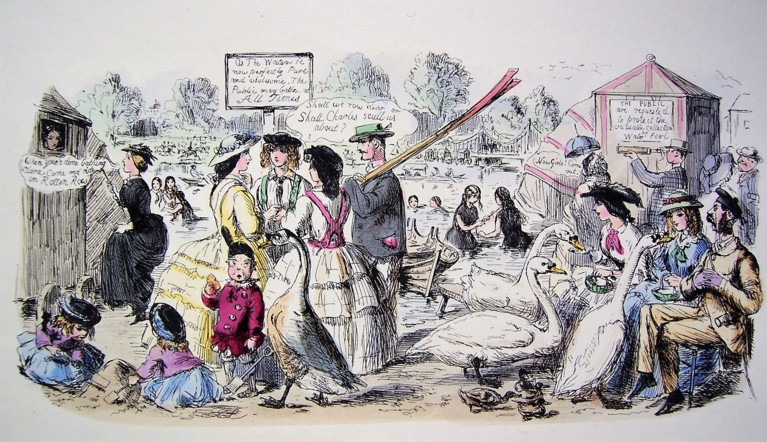

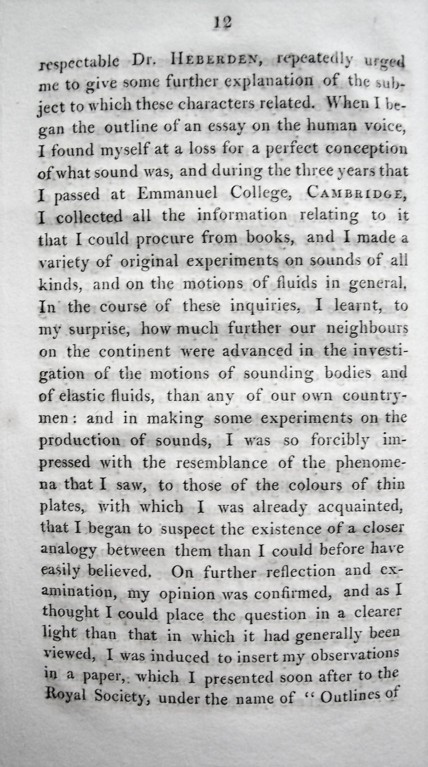

A curious public inspects the curiosities in the museum at Trinity College Dublin; W. B. Taylor, History of the University of Dublin (1819)

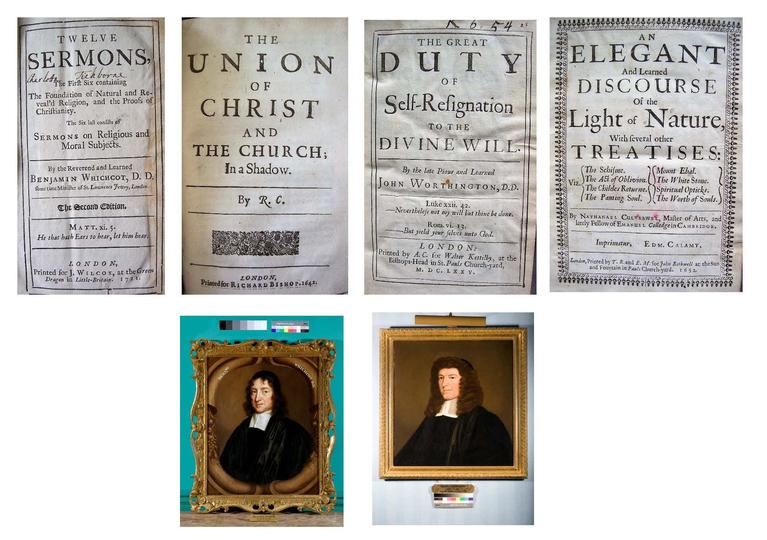

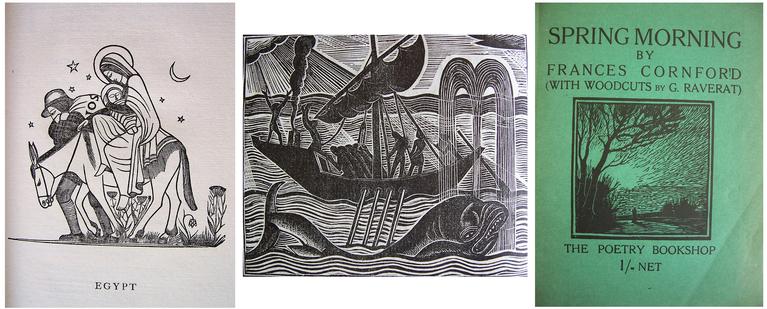

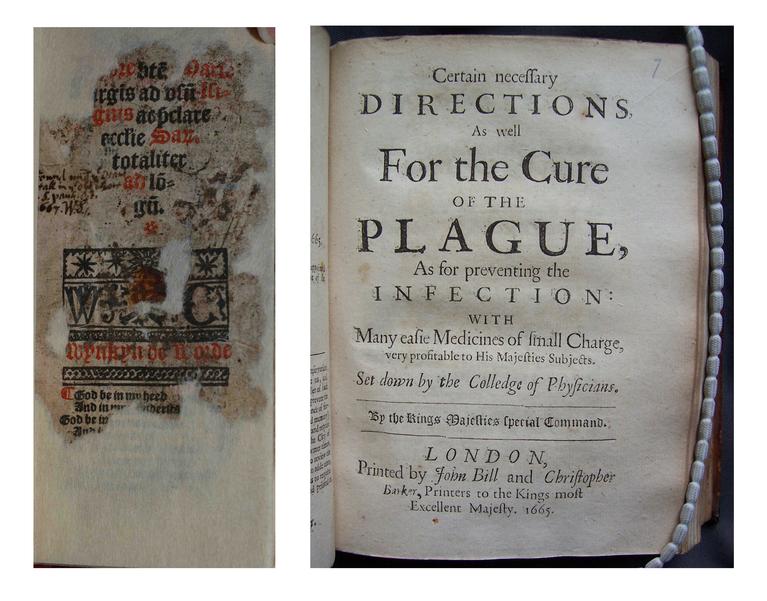

Emma Connects has just passed its one hundredth edition since it was created in order to reach out to Emmanuel members during the isolation, and perhaps loneliness, of the first lockdown. Soon it will be four years since the first Rare Book blog appeared in April 2020, describing a book published in 1665, the year of the Great Plague, that recommended ‘It is advisable that all needless Concourses of People be prohibited …’ This is the sixty-fourth of these Rare Book blogs since that beginning, although they have barely scratched the surface of the College’s rare book collections. The positive outcome of what began prompted by adversity is that the interest and beauty of Emmanuel’s illustrated books – many now quite fragile to handle – can be appreciated by a much wider readership than ever before.

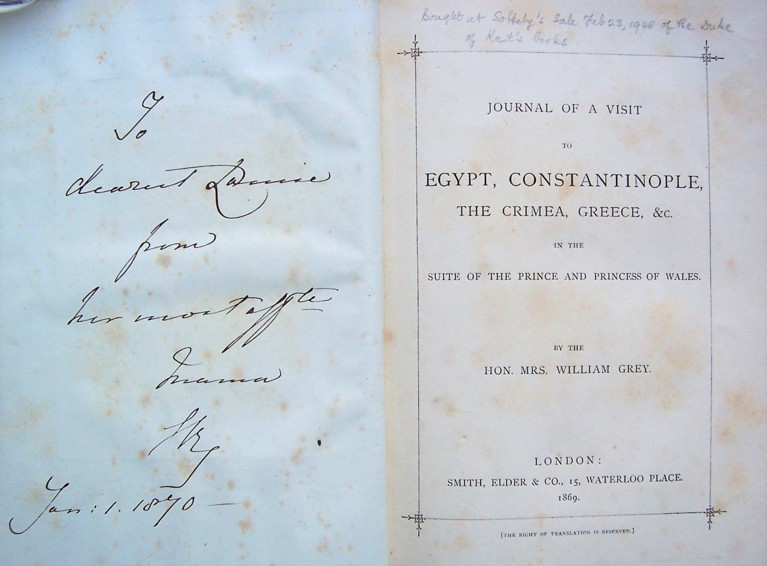

What never ceases to impress is the sheer energy of curiosity represented by those who created these books and those who collected them. Two books written by intrepid women make this point. The title page of Narrative of a Residence at Tripoli in Africa (1816) gives the author as Richard Tully, but the introduction at once acknowledges that the memoir is that of his sister, recalling experiences from thirty years earlier, when Tully was the British Consul at Tripoli, and his young daughters grew up speaking Arabic and on terms of close friendship with the family of the Bashaw, or ruler, of Tripoli.

Miss Tully, Narrative of a Residence at Tripoli: Officers of the Grand Seraglio Regaling

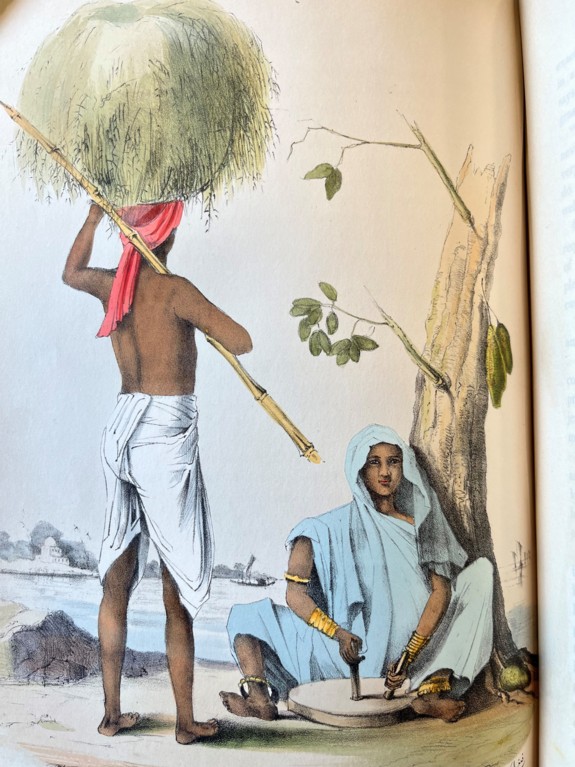

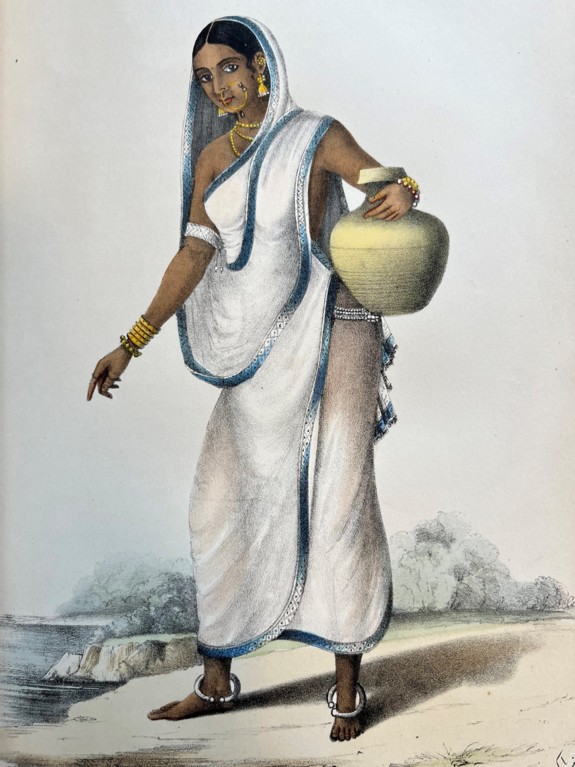

Fanny Parks published extensive journals of her time and travels in India as the wife of a British official in Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, during four-and-twenty years in the East (1850), but in a self-effacing gesture her name appears on the otherwise-English title page only in Urdu script. She is a sympathetic admirer of Indian culture and customs, sometimes allowing herself to criticize such English ways as the legal position of married women.

Fanny Parks, Wanderings of a Pilgrim: Grass-Cutter and Gram-Grinder; A Bengali Woman

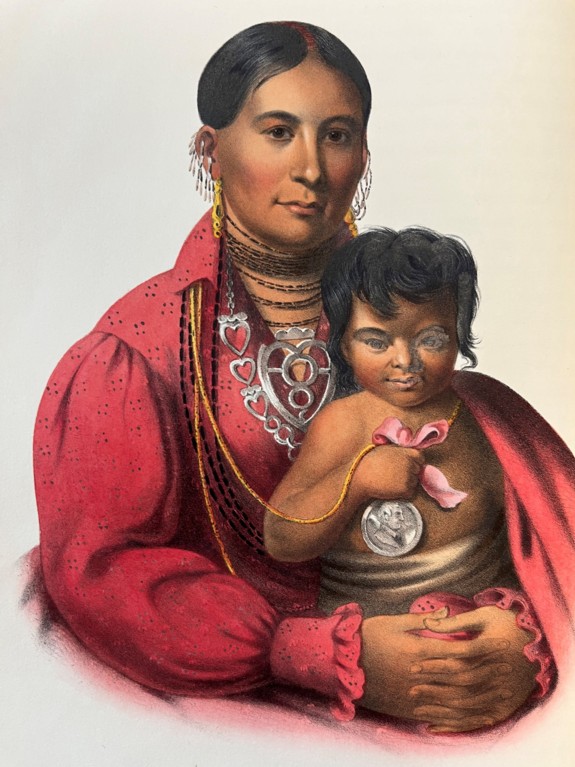

Thomas McKenney and James Hall’s, History of the Indian Tribes of North America (Philadelphia, 1848-50) was based on portraits commissioned by McKenney of Native Americans who came to Washington to negotiate treaties. McKenney was Superintendent of Indian Trade and hoped to preserve ‘whatever of the aboriginal man can be rescued from the destruction which awaits his race’. With the advantage of hindsight, it is hard not to see that doomed dignity in the solemn composure of these portraits.

McKenney and Hall, History of the Indian Tribes: An Osage Woman; A Chippewey Chief

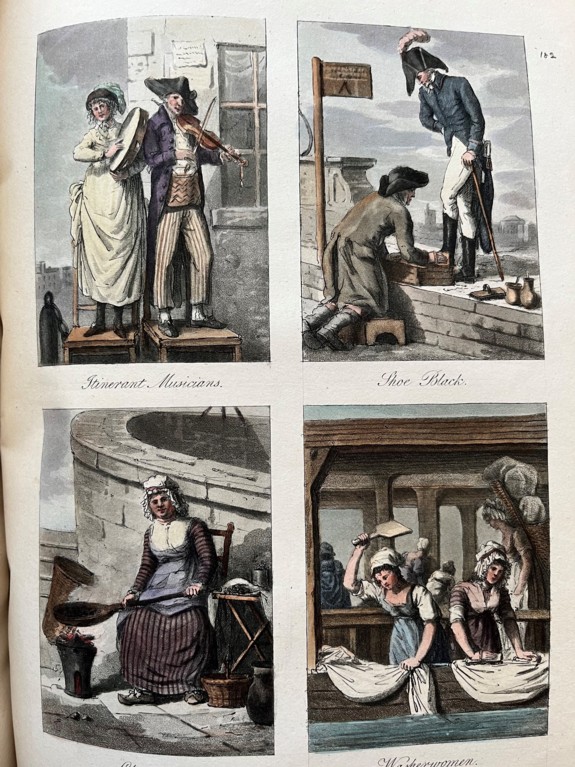

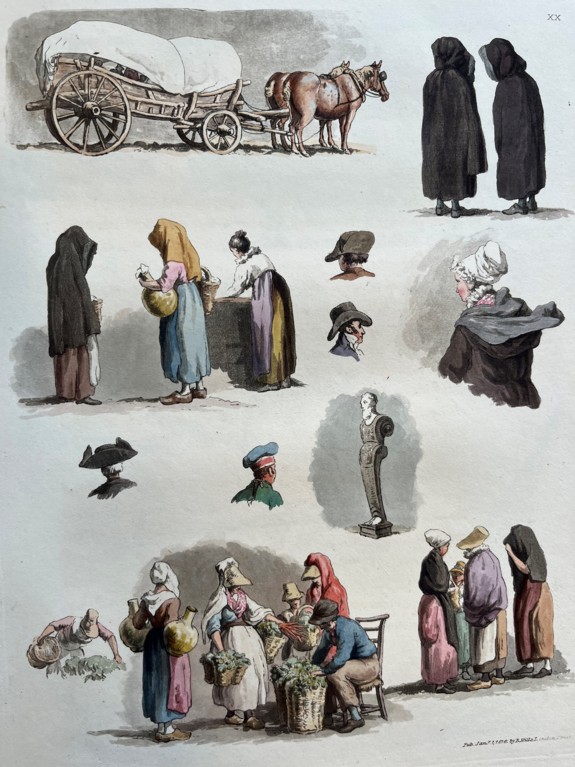

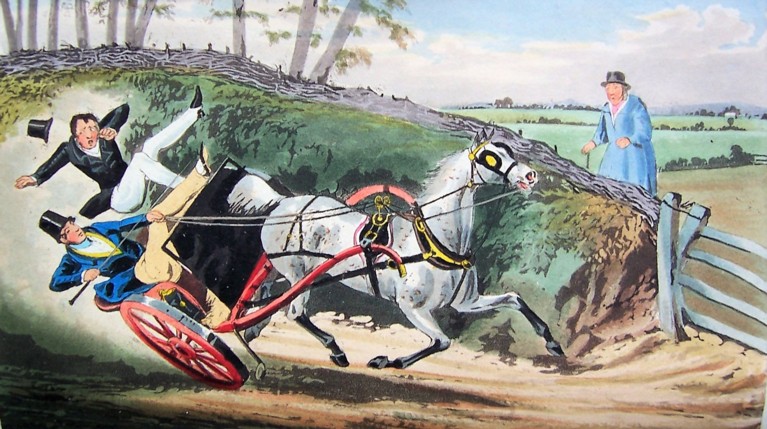

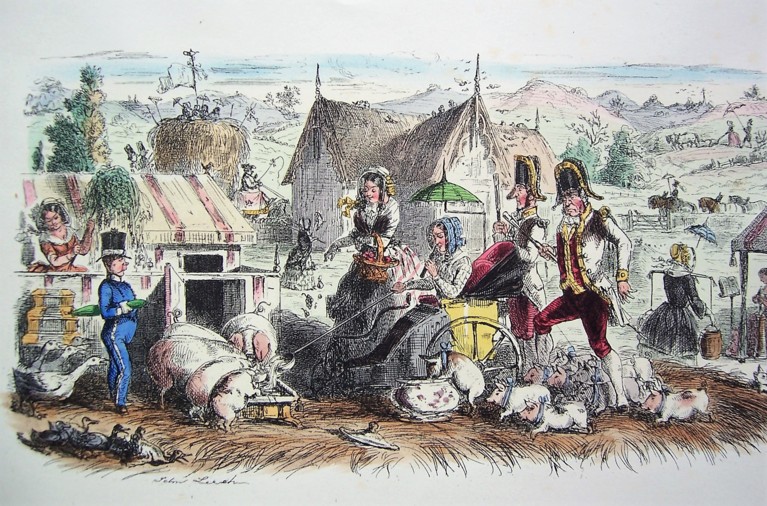

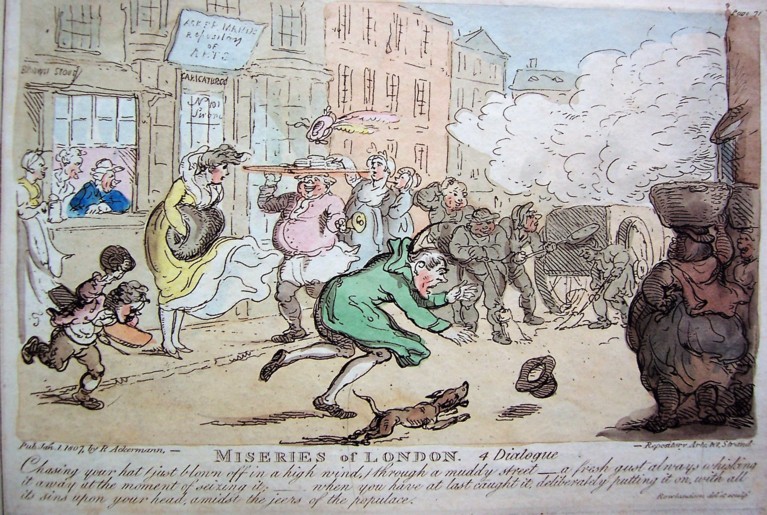

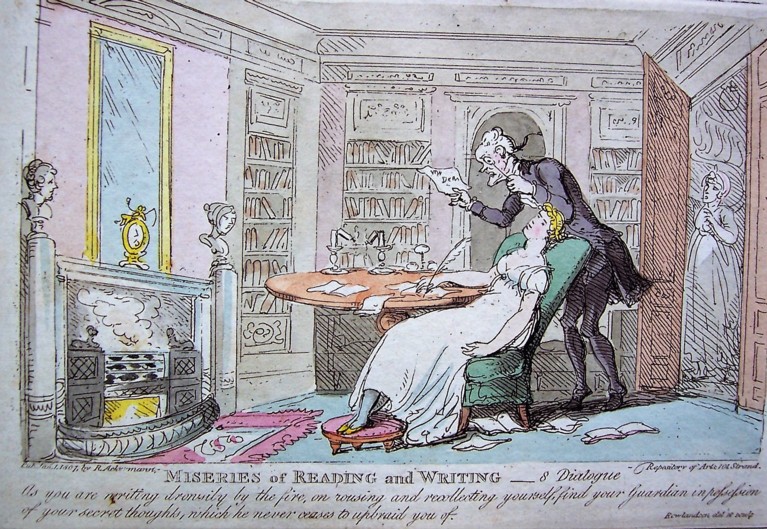

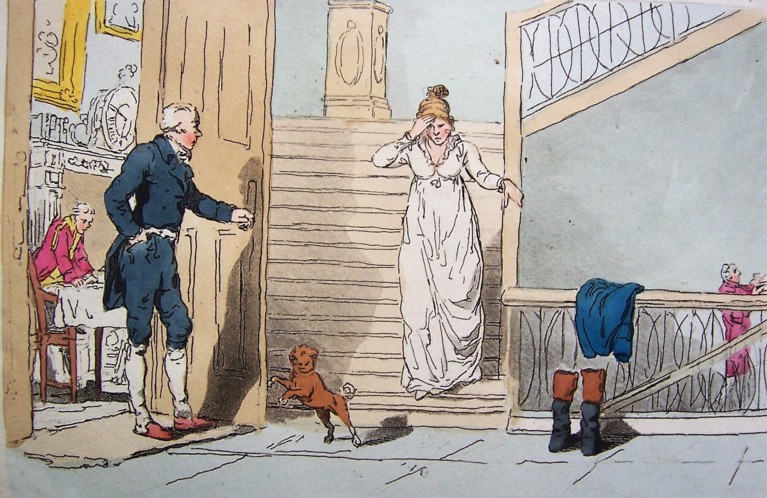

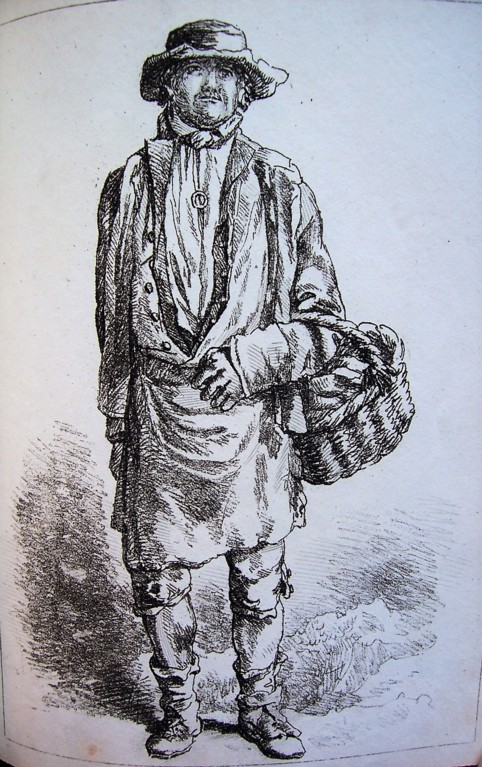

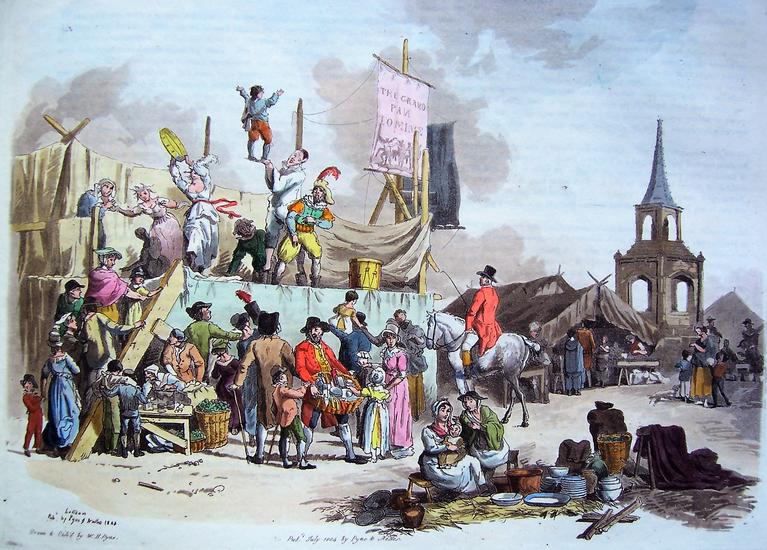

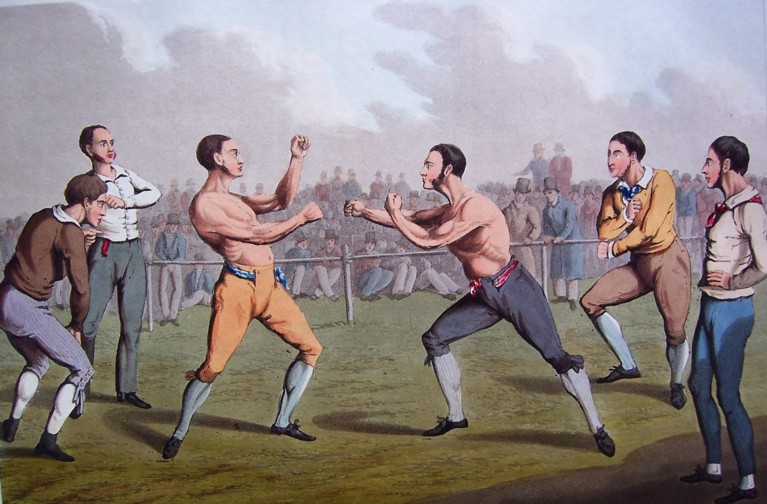

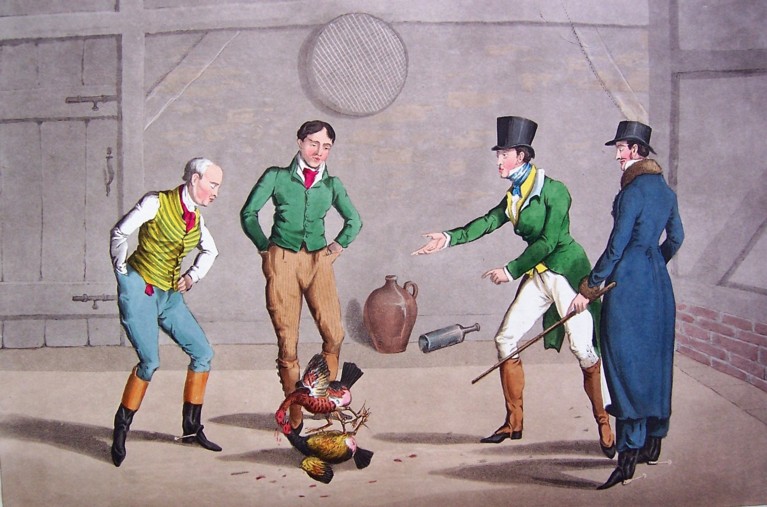

But the customs and costumes of countries much closer to home might prompt just as much curiosity. Both A Sporting Tour through France (1805) by Colonel Thornton and Sketches in Flanders and Holland (1816) by Robert Hills find space, in books largely devoted to views of landscape and architecture, to include studies of figures in local costume in the Low Countries or engaged in their trades on the streets of Paris.

Thornton, A Sporting Tour: (clockwise) Itinerant Musicians, Shoe Black, Washerwomen, Hot Chestnut Seller

Hills, Sketches in Flanders

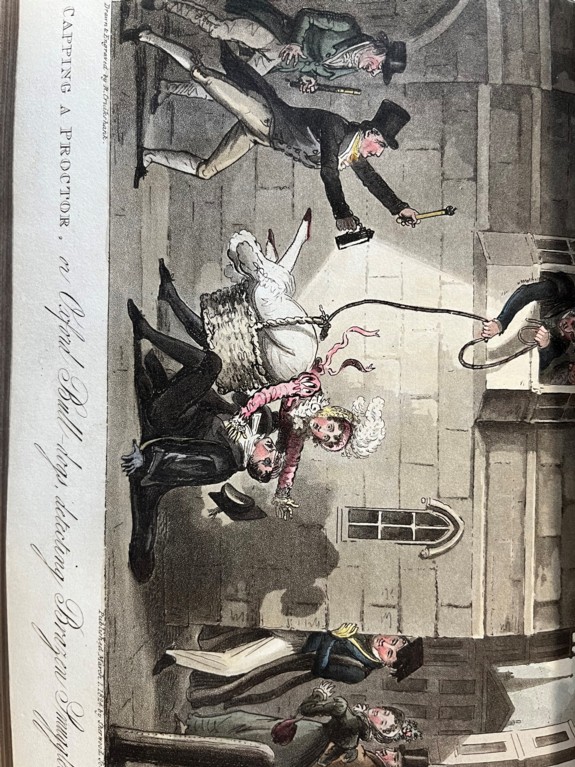

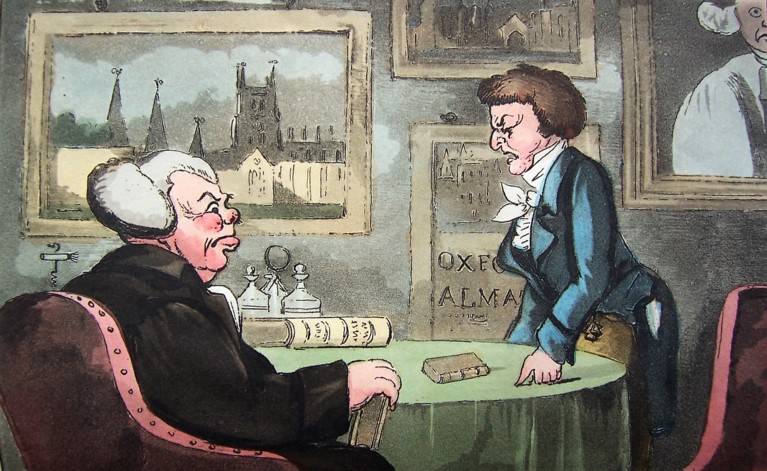

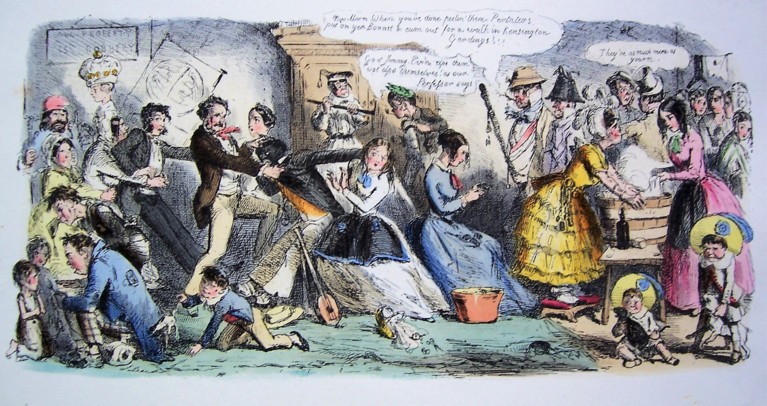

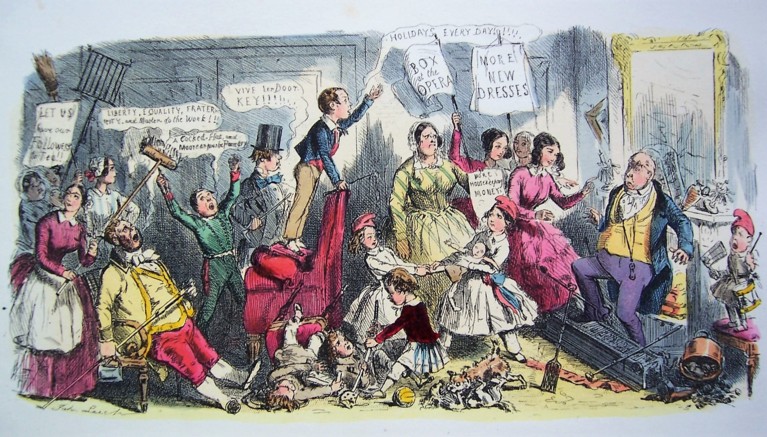

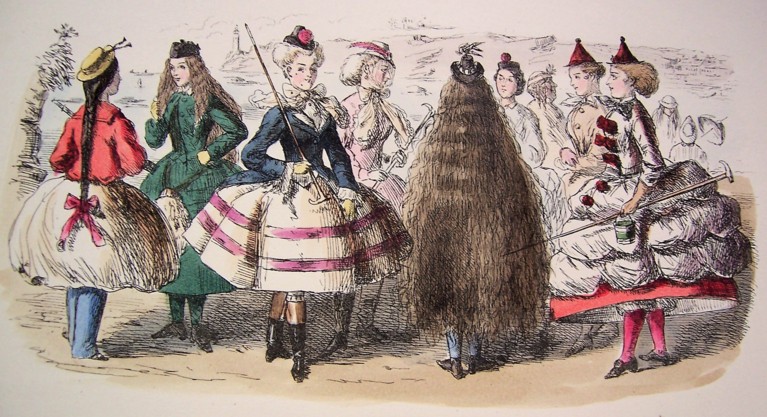

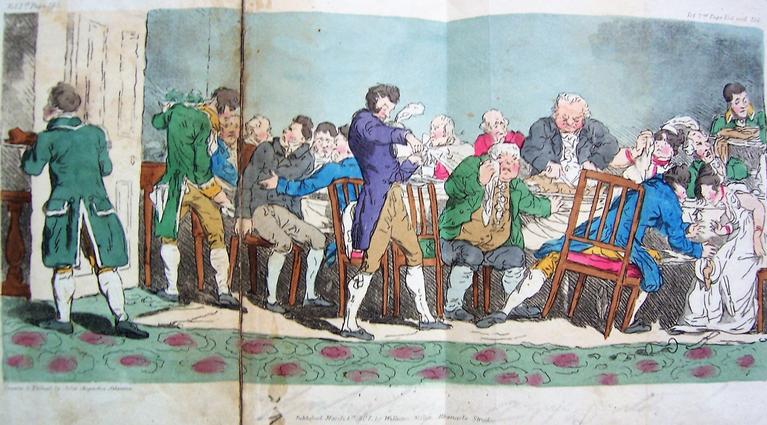

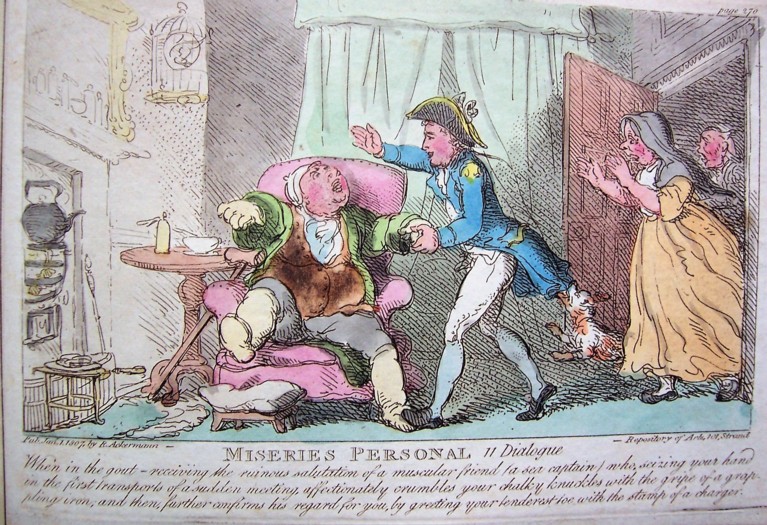

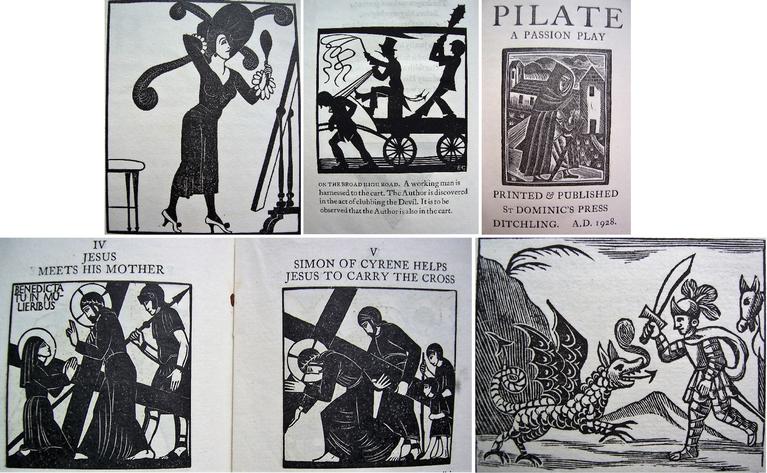

There are also a wealth of illustrated books presenting a wry, serio-comic take on the life of the well-to-do, which often includes a spell at university (more usually Oxford than Cambridge), where comic misdemeanours can be illustrated, as in this plate drawn and engraved by Robert Cruikshank, showing an undergraduate hoisting a ‘fair nun of St Clement’s’ up to his room in a basket, only to succeed in dropping her on to a passing proctor. (He is sent down).

William Westmacott, English Spy: ‘Oxford Bull-Dogs detecting brazen smuggling’

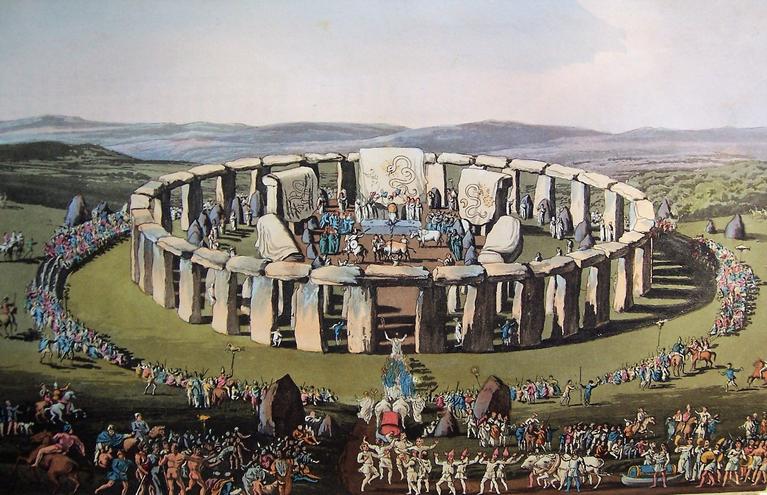

W. Sams, The Tournament

Such illustrations perhaps appeal both to the curiosity of those who haven’t been to college and to the nostalgia of those who have. A new nostalgia is also stirring for a re-imagined version of a ‘Gothick’ medieval past where valiant knights rescue swooning damsels from unwelcome oppressors, as in the illustrations to a truly dreadful book-length poem, The Tournament, or, Days of Chivalry (1823).

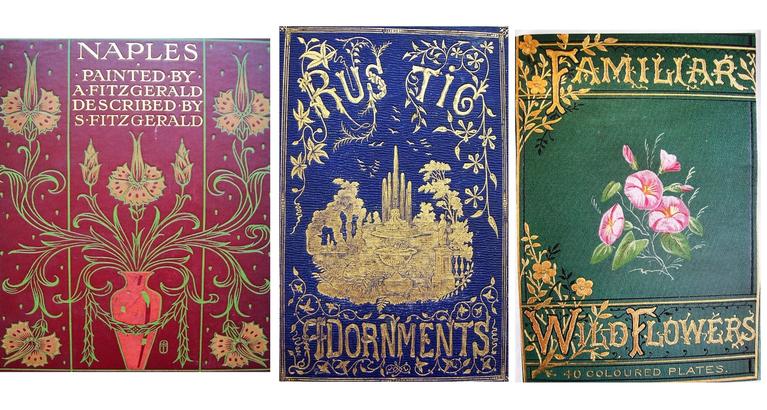

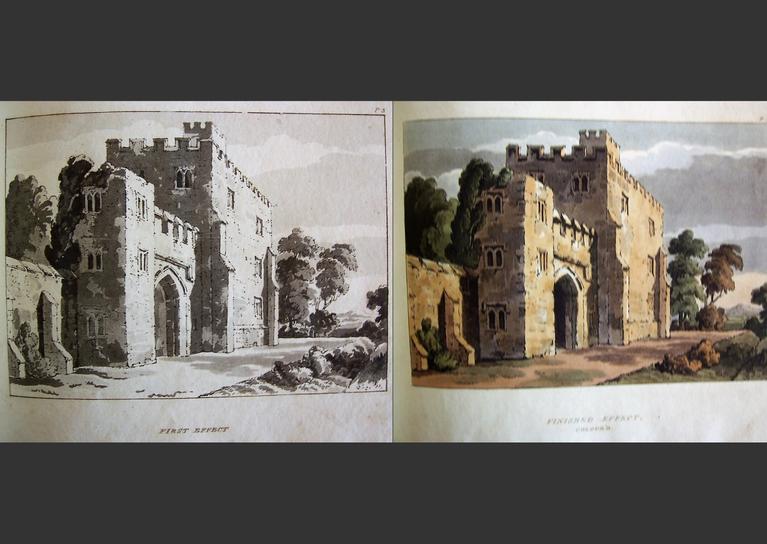

Another spur to curiosity for illustrated books probably lay in how so many of the early readers of such illustrated books – both men and women – will themselves have been taught to draw and paint as part of a polite education. Many of the flower books in the College’s collection present both a coloured and uncoloured version of each flower, with the latter available to be coloured by the owner.

Miss J. Smith, Studies of Flowers from Nature: ‘Dahlia’ coloured and uncoloured versions

Such books are directed at purchasers who may well have had a trained eye for painting in water colours every sort of subject from flora and fauna, but especially flowers and birds.

Thomas Martyn, Aranei; or A Natural History of Spiders (1793), frontispiece

Edouard Travies, Les Oiseaux: scenes varies, etudes a l’aquarelle (1857): Bird of paradise

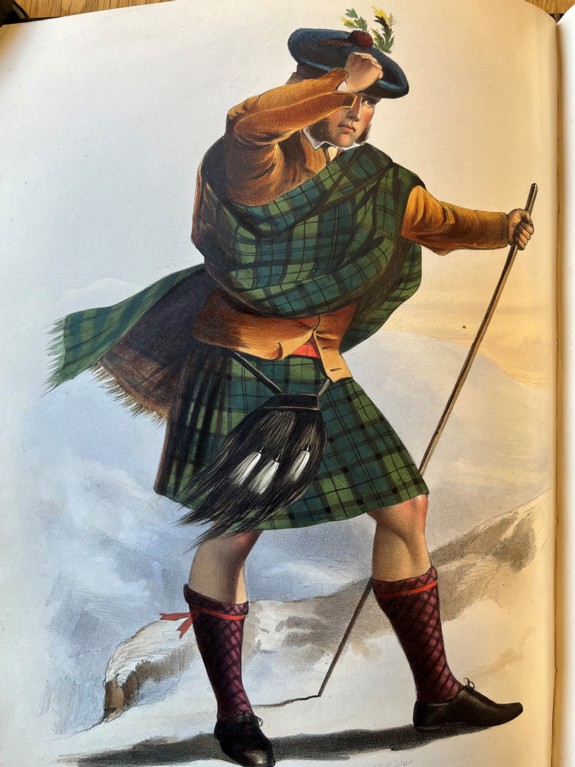

Curiosity goes along with innovation in the superb illustrations of clansmen in their tartans in McIan’s The Clans of the Scottish Highlands, 2 vols. (1845-57).

R.R. McIan, Clans of the Scottish Highlands: ‘Sutherland’, and Frontispiece to Volume 2

For although the pictures of clansmen are hand-coloured lithographs, the two magnificent heraldic title pages are successful early examples of colour printing. ‘Printed in colors’ (sic) it says modestly in very small type at the foot of the page, but this is part of a transition to a whole new future in the production of illustrated books.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

28 February 2024

February has almost gone. Most of it was disrupted by the rain again, with just the odd exception in the form of a sunny break in the clouds. I think 2023 and the start of 2024 is one of the dampest gardening seasons that I can remember in 30+ years of gardening. For some, it has been a welcome spell compared with the previous seasons’ long hot spell. I suppose that, as a gardener, you must be careful what you wish for. On the plus side, the temperatures have been on the mild side. There have been good signs of early spring growth. We have even had to make an early start to our grass cutting schedule as the grass has put on significant growth.

February is always a busy month in the Emmanuel gardens. It is the phase where we are preparing for the coming seasons ahead. We have been busy maintaining all the college benches during the wet spells. Every year there seem to be more benches to maintain as, unfortunately, the number of memorials has not slowed down.

It is also time to start repairing some of the many pathways throughout college as they get worn and damaged through the winter periods. The Garden Team have been busy making a start on these repairs.

This task has been made a little easier this year due to the garden department’s latest addition. The department welcomes Martin Place to join our fantastic team. Martin joins us as our Landscape Gardener and has brought with him his 25+ years of invaluable experience. Prior to joining Emmanuel, Martin had been proprietor of Saunders Landscapes, which had an excellent reputation in the industry. We will tap into Martin’s skills to help upscale the rest of the garden staff.

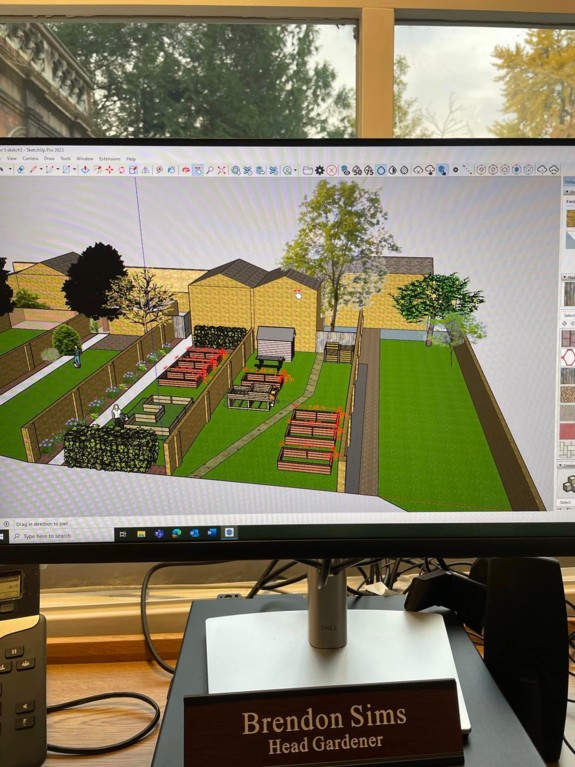

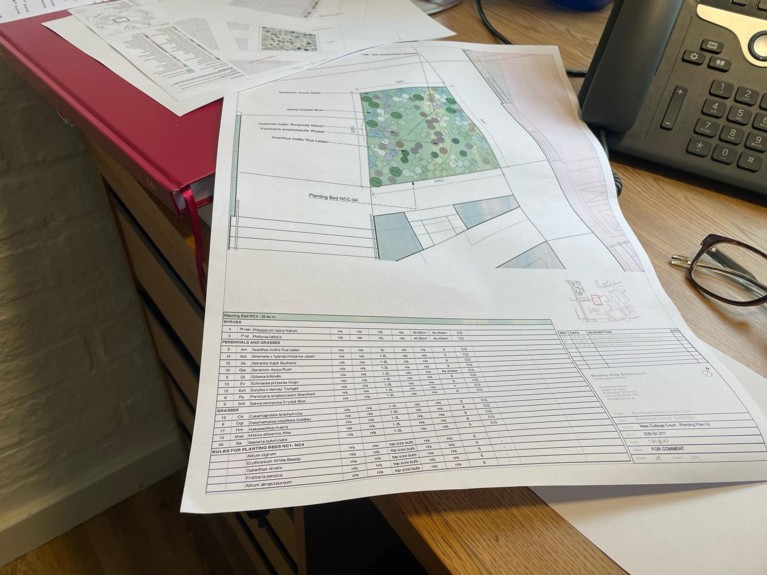

Martin will be very busy in the next few months as we have lots of exciting projects on the horizon. I am delighted to announce that, after many months of hard work and an untimely delay, we have eventually had confirmation of the funding required for the Emmanuel College Community Garden. We will be shortly making a start on the building of this, with hopefully some of it being ready to use this year.

We are also busy trying to re-landscape the swimming pool area after several months of construction left the grounds in a bit of a mess.

Over the next few months, the Gardening Department will be collaborating much more with the college sports ground. I am keen to work with our excellent Groundsman, Mark Robinson, in a closer partnership, which I think will benefit both the sports ground and Emmanuel gardens. I am keen for college sport to return to its pre-Covid days and will be working with Mark to ensure we are heading in the right direction.

The Emmanuel gardens themselves are starting to wake up. The earliest signs of spring bulbs are poking through. It always gives us gardeners a sign of hope for warmer days to come.

In March (on Monday 11th), we are delighted to welcome Charles Dowding back to his old college to give us a Masterclass and an evening talk regarding his now famous ‘No Dig’ philosophy. It’s not every day a celebrity horticulturist comes to Emmanuel, so the department are very excited. There are just a few spaces left if you want to join us. Booking is through Emma Experience and Daniel McKay.

Best wishes.

Brendon Sims, Head Gardener

28 February 2024

The London Overground map is undergoing a revamp. Its wandering orange lines will be replaced by new colours and names denoting the six segments that make up the system. The route between Stratford and Clapham Junction/Richmond has been designated the ‘Mildmay Line’, sparking considerable interest among Emma Members.

The route’s name commemorates the Mildmay Mission Hospital, founded in 1877. Since 1988, it has been a specialist centre for patients with HIV. The hospital was one of many charitable organisations set up by Canon William Pennefather and his wife Catherine, who lived in an area of Newington Green known locally as the Mildmay estate. This quarter had been developed for housing in the mid-nineteenth century, and the ubiquity of ‘Mildmay’ in the resulting nomenclature – Street, Road, Avenue, Grove, Park – is a sure indication that the land had formerly belonged to a family of that name.

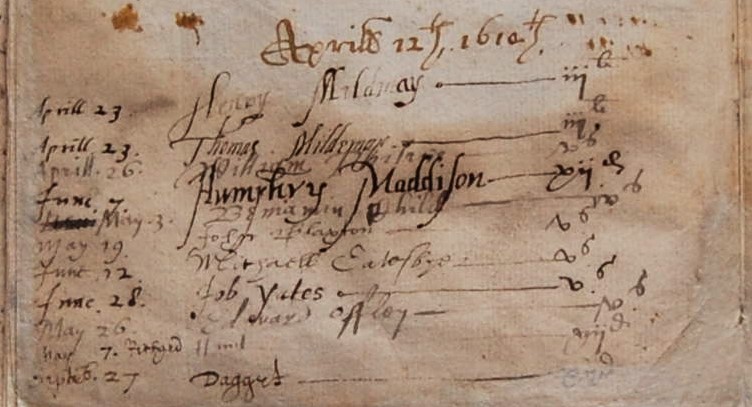

Henry Mildmay’s signature in the college admission book; Thomas Mildmay, admitted on the same day, was his cousin

Henry Mildmay, born c.1594, was a grandson of Emmanuel’s Founder, Sir Walter Mildmay. Admitted to Emmanuel in 1610, he continued to take an interest in college affairs after graduating. In 1627, for example, he opposed the royal mandate suspending the unpopular De mora statute that forced Emmanuel Fellows to leave after ten years and become beneficed clergymen. Henry offered to present the college with ‘five or six’ benefices to which its Fellows could be appointed, on condition that the suspension was revoked. The King agreed, but cannily insisted that the college got the benefices first. Henry failed to deliver.

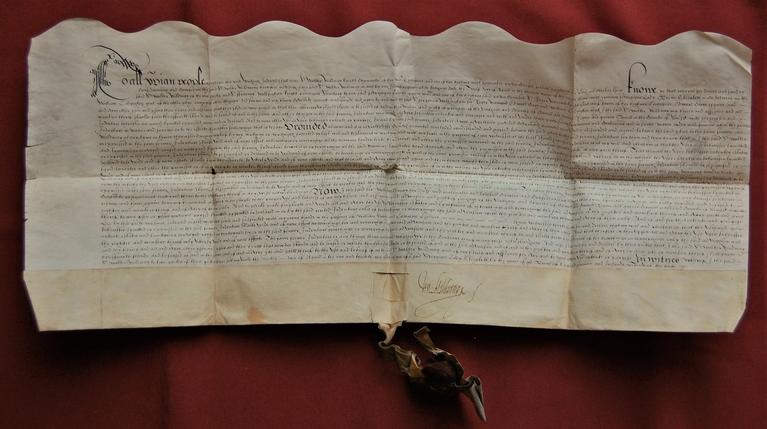

Knighted in 1617, Sir Henry was MP for Maldon from 1621 and held several important official posts, including Master of the King’s Jewel House. His rapacity regarding the perks of office was notorious. Originally a royalist, he switched allegiance during the Civil War and attended Charles I’s trial, although he stopped short of signing the King’s death warrant. He was nevertheless sentenced to life imprisonment at the Restoration; his estates were forfeit, and he was exiled to Tangiers, where he died in 1668. Given his cupidity, Sir Henry had naturally sought a wealthy bride. The lucky lady was Anne, daughter and co-heiress, with her sister Margaret, of William Halliday, a vastly wealthy London alderman. Henry enlisted the help of the King, no less, to coerce the girl’s suspicious father into permitting the betrothal, which took place in 1619.

William Halliday had a house and copyhold estate in the village of Newington Green, and it was this property that became known as the Mildmay estate. Exactly when the Mildmays acquired full possession of the land is unclear. Sources state variously that it was after Halliday’s death (1624), or his widow’s death (1646), or Anne Halliday’s death (1657). The estate had presumably been divided between the sisters, as Margaret Halliday bequeathed her Newington copyholds to her nephew, Henry Mildmay junior, in 1673.

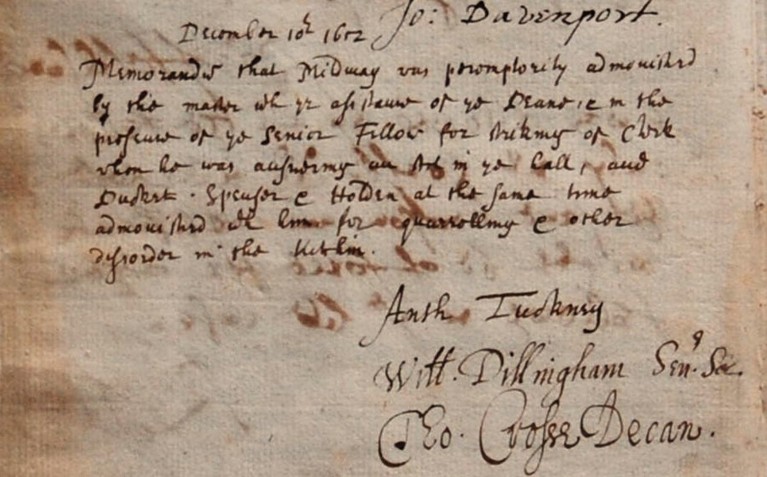

Henry Mildmay junior’s admonition for ‘striking of Clerk’ (either John Clarke or Samuel Clarke, sizars)

Henry junior followed his father to Emmanuel, being admitted in 1651. The apple may not have fallen far from the tree, as he was ‘admonished’ in December 1652 for hitting another student (the only founder’s kin to receive this formal censure) and was later accused by his elder brother William of having cheated him out of his inheritance. The Mildmay estate in Newington remained in the hands of Henry junior’s descendants until its sale in the late 1850s.

Surviving documentation suggests that, against all the odds, the marriage between Sir Henry Mildmay and his ‘so good a wife’ Anne Halliday was a happy one. Parents to six children, they founded their own ‘Mildmay line’, and gave their name to a little corner of north London. Something to ponder when rattling between Dalston Kingsland and Canonbury…

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

31 January 2024

January has come around fast and the Christmas holidays seem a distant memory. On returning to work, we had to pick up where we left off and the first job back always means recycling the Christmas trees. The season’s unfavourable weather also continued with what has seemed like one named storm after another, after another and another. The Garden Department longs for some spring-like days and some apricity from the winter sun.

Unfortunately, just before Christmas, the department had to say goodbye and good luck to one of our staff members, Andrew Luetchford. We wish Andrew the best and thank him for all his hard work, but also look forward to recruiting and welcoming someone new. Watch this space.

The myth that gardeners are not busy in the gardens at this time of year could not be further from the truth. There are multiple tasks that need completing in the winter months – a long list of pruning schedules that roll out almost until the spring. It is a time for pruning and tying in the climbers, such as wisteria and climbing roses, and with the help of the Maintenance Department, we added brand new climbing supports to our new buildings. The supports look great and will give good support to the climbing plants on those buildings to help soften the landscape.

When the sun does shine in the winter, it enhances the beautiful fragrances from some of our winter shrubs. Some of the highlights come from the winter border in the Fellows’ Garden. The colours and fragrances at this time of year can be wonderful, including the Chimonanthus praecox (Wintersweet), Hamamelis (Witch hazel) and the winter flowering Viburnums (Viburnum x bodnantense). The smell from the Sarcococcas (Sweet box or Christmas box) can be heavenly as you brush past them.

It is also a time to start to work our way through preparing the herbaceous borders. The foliage is left as long as possible to provide some winter protection for the insects, but there must be a systematic plan as we go forward to manage the borders. A comprehensive approach through mass and void analysis helps determine which plants we need to be split and divided through the season, and if indeed any replacements are required.

Once the borders are managed then mulching can begin to take place and adding a rich organic matter to the borders will help replace spent nutrients, lock in moisture and help with weed suppressing as the soil temperatures rise. This is a good practice annually and most of the mulch will come from our home-grown compost.

Something to look forward to this year is the college spending some time with celebrity gardener Charles Dowding. Charles is an Emma alumnus and is infamous for his ‘no dig’ theories. Charles will be visiting the college on 11th March and giving a talk in the Queen’s Theatre – this is something that has got the Garden Department very excited. Look out for more information about this shortly.

Best wishes.

Brendon Sims, Head Gardener

31 January 2024

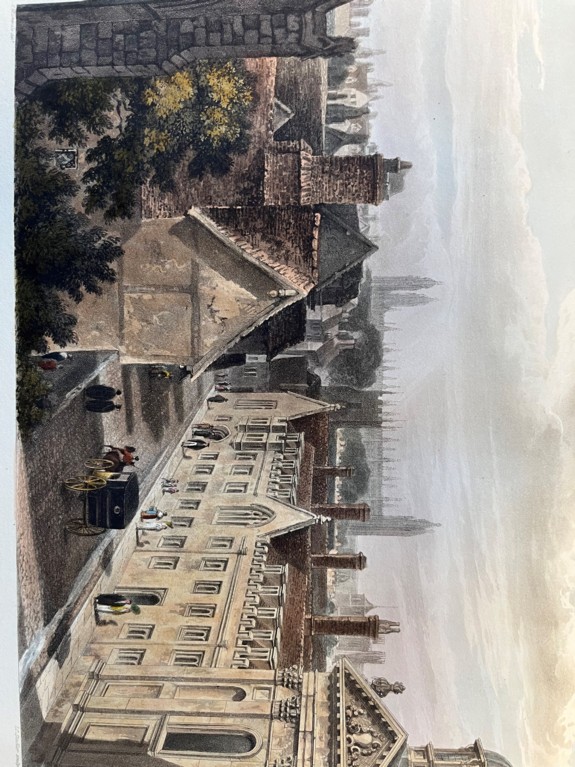

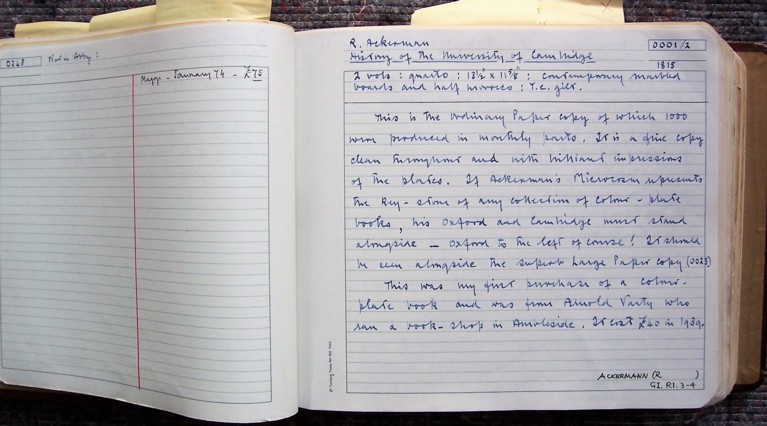

R. Ackermann, History of the University of Cambridge (1815), ‘Pembroke Hall etc., from a window at Peterhouse’

Visitors viewing the richly illustrated books in Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection often wonder why such a flowering of hand-coloured books and prints occurs in Britain at this time, roughly the first three decades of the nineteenth century. Breakthroughs in the technical processes of aquatint and lithography are the key contributing factor. But another major influence was the entrepreneurial genius of Rudolph Ackermann (1764-1834), a passionately Anglophile German immigrant publisher. His publication of a series of lavishly illustrated histories of Oxford, of Cambridge, and of historic public schools, were shrewdly pitched to appeal to an elite market among their alumni, but they were also so beautiful that they continue to shape perceptions of those places.

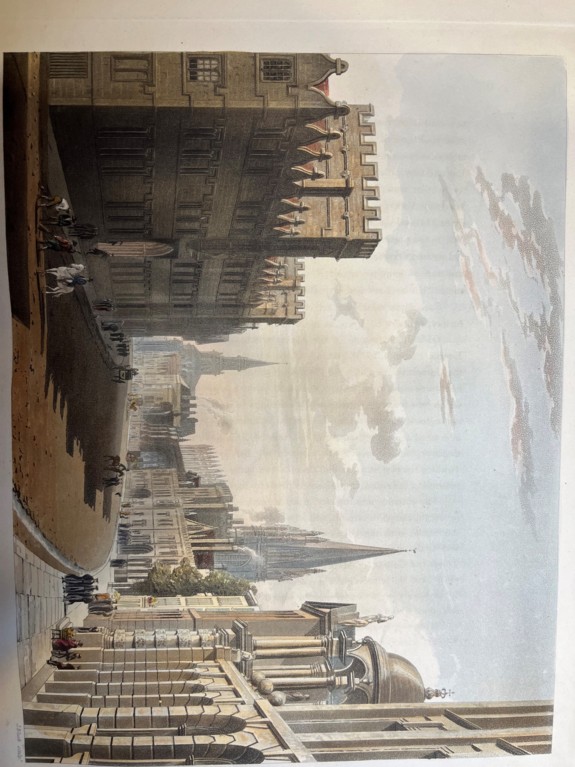

R. Ackermann, History of the University of Oxford (1814), ‘View of Oxford, taken from New College Tower’

‘Oxford, High Street, Looking West’

After an early career as a coach-builder and designer in Germany, Ackermann arrived in London in 1787, initially to pursue the same business. But by 1797 Ackermann had opened ‘The Repository of Arts’, a shop in the Strand famous in its day for pictures, prints, illustrated books, as well as paper, paints and artists’ materials aimed at the burgeoning market of amateur artists. These elegant premises became a fashionable haunt for those who wanted to be seen to have sophisticated tastes, not only in art but in fashion and décor. Tea and lectures were available. From 1809 Ackerman published a monthly magazine, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics, full of articles and illustrations of fashion, furniture and social news. During its twenty-year run, The Repository published over 1400 hand-coloured plates. The fashion plates, sometimes with dress-making patterns, were immensely influential on women readers.

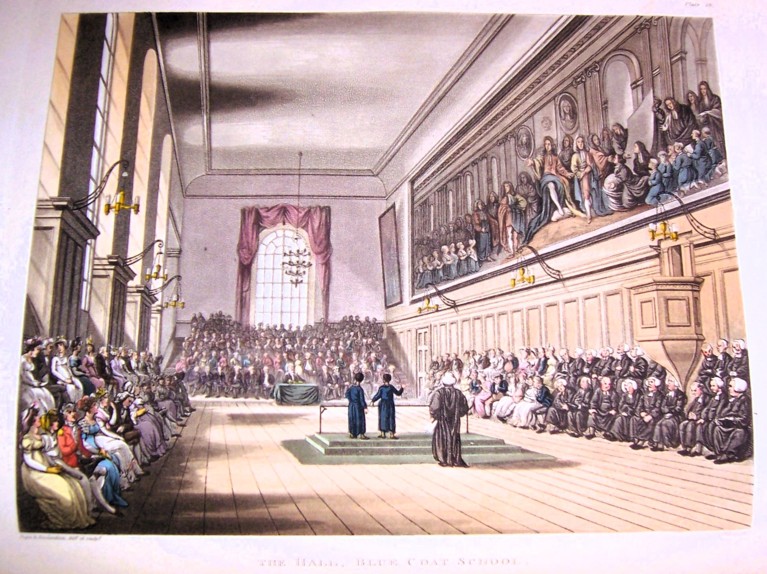

From publishing prints there was a logic in Ackermann’s move into publishing illustrated books, such as his sumptuous three-volume Microcosm of London (1808-1810), containing 104 hand-coloured aquatints, with outside and inside scenes of London landmarks and institutions. The plates are often revealing of current social practices, such as visitors to an exhibition of watercolours, or a ‘speech day’ event at the Blue Coat School, where two scholars – known as ‘Grecians’ and destined for Oxford or Cambridge – were required to recite orations ‘in praise of this institution, one in Latin and the other in English’.

Microcosm of London (1808-1810), ‘Exhibition of the Society of Painters in Water Colour, Old Bond Street’

Microcosm, ‘The Great Hall, The Blue Coat School’

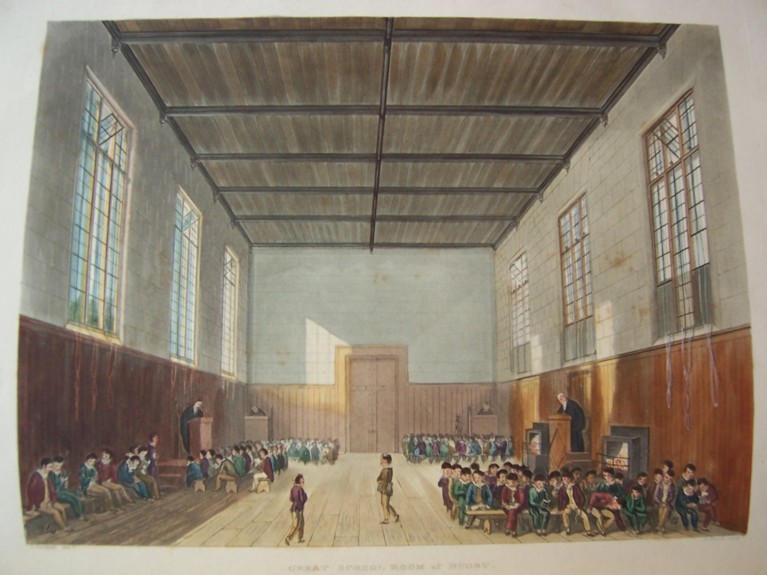

Like the Microcosm of London, Ackermann’s history of the public schools has a profusion of plates highlighting picturesque views of ancient buildings, so it is valuable that just one plate for each school actually provides a record of the educational process in these institutions, and a surprising one to modern eyes in terms of ‘class size’.

History of the Colleges of Winchester etc. (1816), ‘Eton College, School Hall’

‘The Merchant Taylors’ School Room’

In each of the schools, the plates show instruction of large groups of pupils by a number of teachers taking place within one very large, hall-like room. The competing noise must have been both a distraction and perhaps a training in concentration.

‘Harrow School Room’

History of Rugby School (1816), ‘Great School Room’

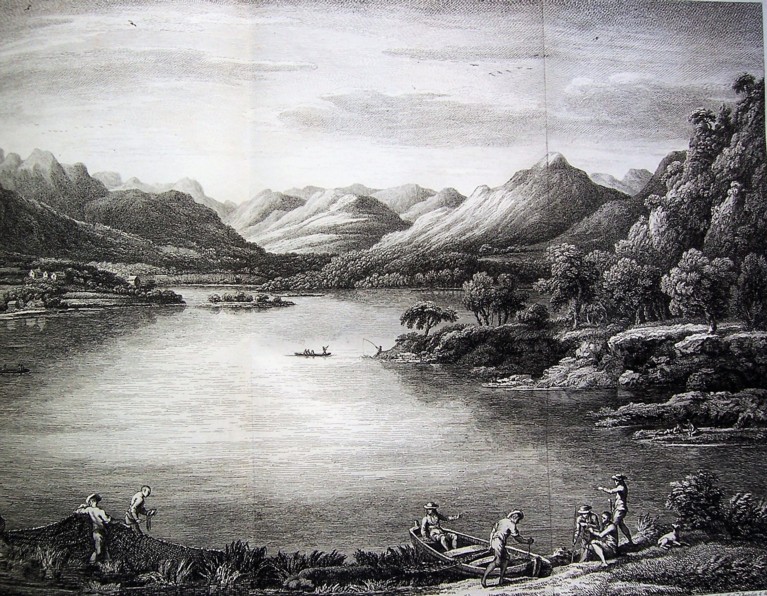

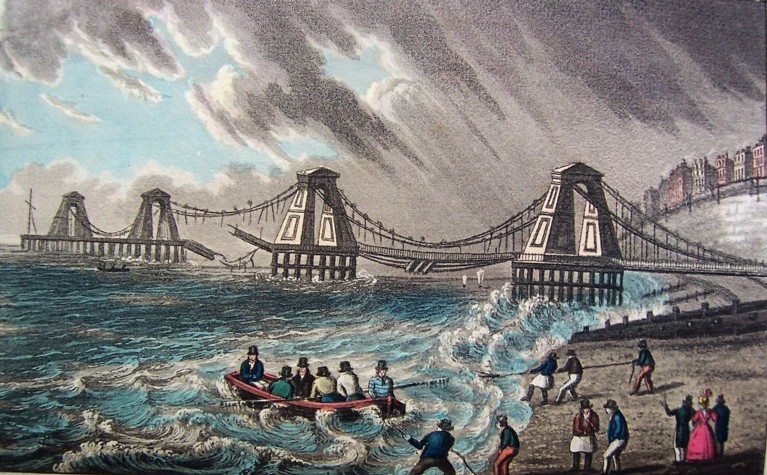

With a sixth sense for trends, Ackermann also catered to the fashionable taste for appreciation of picturesque scenery, and for books that allowed the armchair traveller to view landscapes with picturesque qualities and their inhabitants (including the clans of the Highlands). He published armchair tours of the picturesque beauties of the Rhine, and the Seine, and the coast of Ireland.

A Picturesque Tour of the Seine (1821), ‘Andeli’

Illustrations of the Landscape and Coastal Scenery of Ireland (1835), ‘Gap of Dunloe, Killarney’

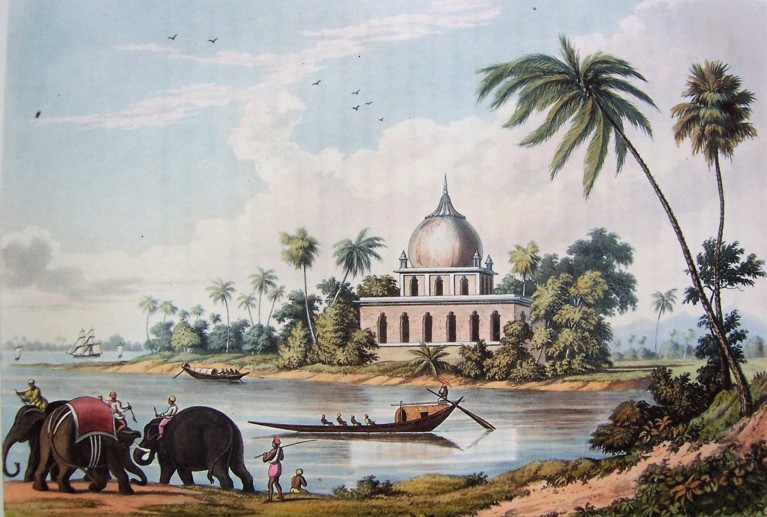

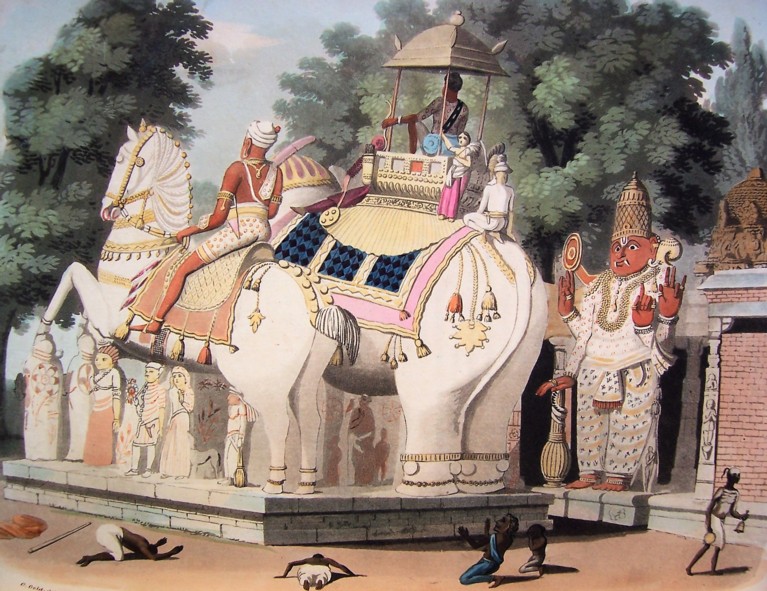

Further afield, Ackerman published a picturesque tour of the Ganges, and a history of Madeira with delightfully quirky illustrations.

A Picturesque Tour along the Rivers Ganges and Jumna (1824)

A History of Madeira (1821), Getting about on Madeira by Hammock-Mobile

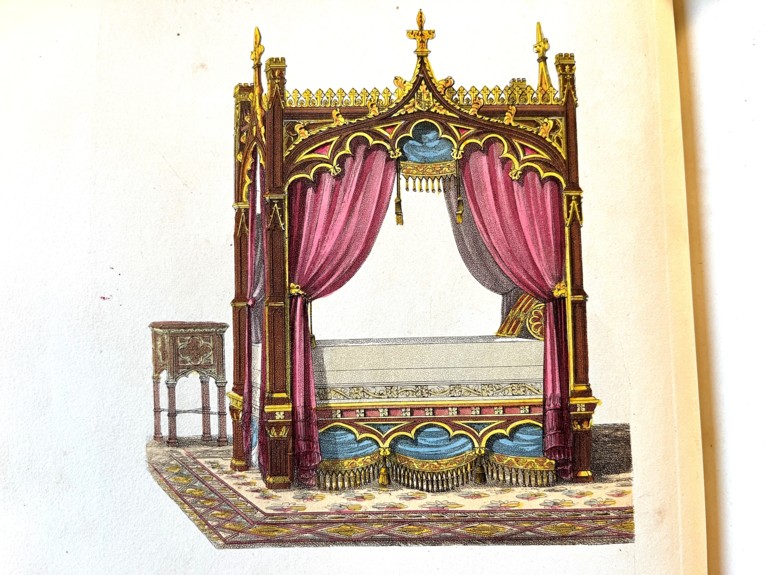

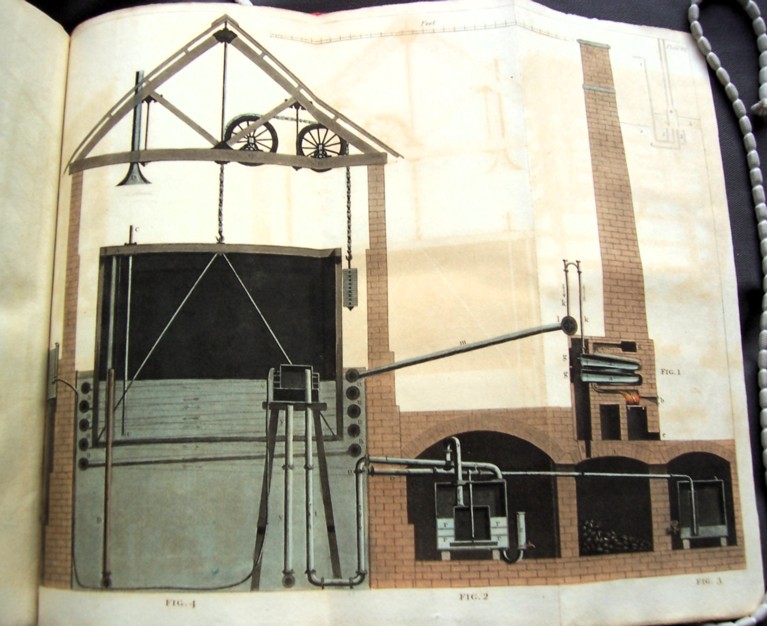

In none of these books were the texts written, or the illustrations drawn, engraved or coloured by Ackerman himself, but he employed the best artists and engravers of the day. This included publishing the cutting political and satirical caricatures of Thomas Rowlandson, as well as the more fastidious genius of Augustus Pugin, whose book of idiosyncratic designs for furniture in the ‘Gothick’ taste was published by Ackermann. Always the innovator, Ackermann’s shop on the Strand was illuminated by gas lighting, on which Ackermann published a book, and his own promotion of gas lighting furthered its wider acceptance at the time.

Augustus Pugin, Gothic Furniture, ‘Gothic Bed’

F. Accum, A Practical Treatise on Gas-Lighting (1816), illustrating gas-lighting machinery

He expanded into Latin America, where he supported the liberation movements, and published 100 books in Spanish (but this proved unprofitable and he burned his fingers). Perhaps akin to an obsession with cars in modern times, Ackermann’s engagement with carriage design never left him: in one year he designed both the carriage in which the Pope rode to Napoleon’s self-coronation as Emperor, and the elaborate hearse and the emblems on the coffin for the state funeral of Admiral Lord Nelson. With his inventiveness, his eye for design, and his sheer flair for business, Ackermann may be seen as a pioneer of modern publishing and illustration – and the fruits of that can be seen in the illustrated books in Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection that Ackermann and others published.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

Images: Clare Chippindale

31 January 2024

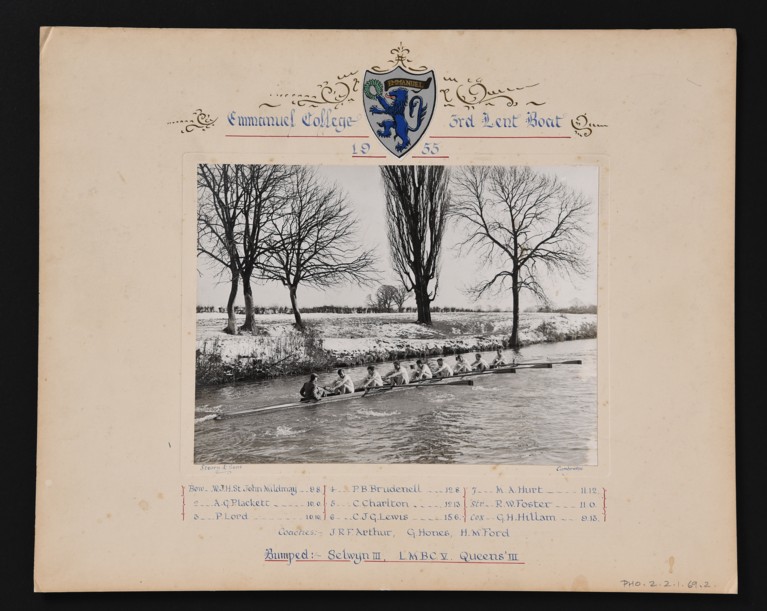

A snowy scene on the Cam in 1955, featuring the Emmanuel 3rd Boat

A snowy scene on the Cam in 1955, featuring the Emmanuel 3rd Boat

The recent blog featuring a photo of the Paddock after the Whitsun snowfall of 1891, prompted John Harding to recall the even more unseasonal snowstorm that swept over Cambridge in the first week of June, 1976. This event was fixed in his memory as he was due to perform in outdoor theatricals at Clare College. It was a case of ‘the show must go on’, despite the perishing cold and consequent meagre (but not, as the cast had hoped, completely non-existent) audiences.

For Cambridge students, snow and ice caused only the usual problems before the mid-nineteenth century: travel difficulties and the risk of catching chills. Once sport became a feature of student life, however, a new dimension of anxiety was born. The Emmanuel College Magazine, which began in 1889, contains annual reports from the Emma sporting clubs, many of them lamenting the effects of icy weather. In Lent Term 1898, for instance, rain and sleet blighted an athletics club fixture involving Hertford College, Oxford, and a similar competition against Brasenose in 1906 had to be cancelled altogether ‘owing to snow’.

Rowing was perhaps the sport most vulnerable to severe winter weather. The Emmanuel boat club report for Lent Term 1895 informed readers that after the Cam had frozen in early February, no rowing was possible for a ‘full fortnight’ and the bumps were subsequently cancelled. The weather in Lent Term 1910 was equally frigid, as noted in the diary of Winthrop Bell, a graduate student from Nova Scotia, who rowed in the college’s 2nd boat. He paints a vivid picture of the miseries, and in his case, dangerous consequences, of winter boating. In late January the oars were ‘frozen’ and there was ‘Ice on river – solid below Ditton’. The weather continued ‘wretched’, and in February Winthrop developed pleurisy. After having several pints of fluid drained from his lungs, a ‘rather nasty job’, he quit Cambridge on medical advice, and transferred to a German university.

.jpg) Skating on the Paddock pond, January 1926

Skating on the Paddock pond, January 1926

The silver lining of sub-zero temperatures, of course, is that ice-skating becomes possible. A photo showing skaters on the Paddock pond in January 1926 would give a modern health & safety officer a conniption, as Emmanuel’s resident pair of swans (who no doubt took a dim view of the proceedings) can be seen swimming on open water near the pond outfall, an indication that the ice was not very thick. Another patch of slushy water is visible against the northern bank, with sweepers standing perilously close. The ‘severe frost’ that produced these conditions prevented any rowing practice and curtailed the Emmanuel golf club’s activities, as noted in the Magazine. A cold snap in 1942 resulted in stretches of water at the Milton sewage works freezing solid. This attracted many keen skaters, including Charles Gimingham, a first year-Nat Sci student at Emmanuel, who recorded in his diary for 17 January: ‘…grand piece of ice…hundreds of people - but room for them all. Major crisis when one’s skates heel slipped and I bust a bolt fitting it - But half hour experimentation on the bank fixed it and the rest was grand.’

Ice on the pond, 1981-2, © Sarah Gill

Ice on the pond, 1981-2, © Sarah Gill

A spell of bad weather towards the end of Michaelmas Term 1980 forced the boat club crews to row during ‘blizzards’ while competing in the Clare Novices. The winter of 1981-82 was much worse, and it is very surprising that the sporting clubs’ reports in the Magazine make no mention of the prolonged snowy and icy conditions. An atmospheric photograph taken that winter by Sarah Gill (née Doole), shows several people skating, or at any rate shuffling, on the frozen Paddock pond at dusk.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

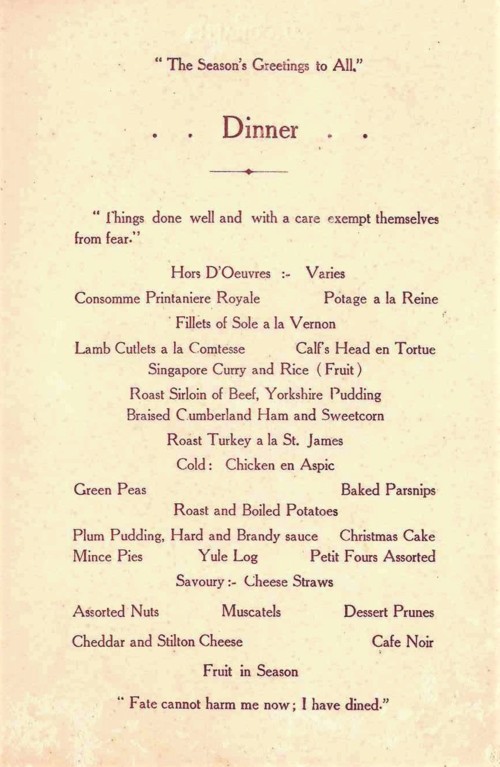

20 December 2023

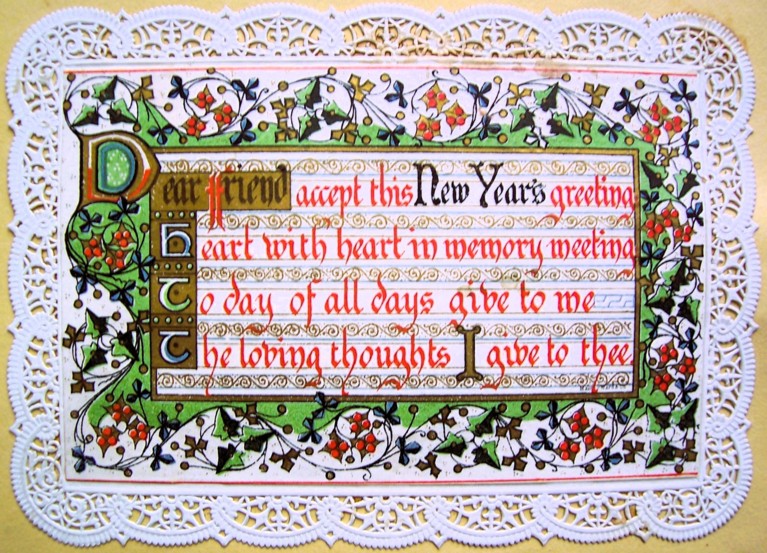

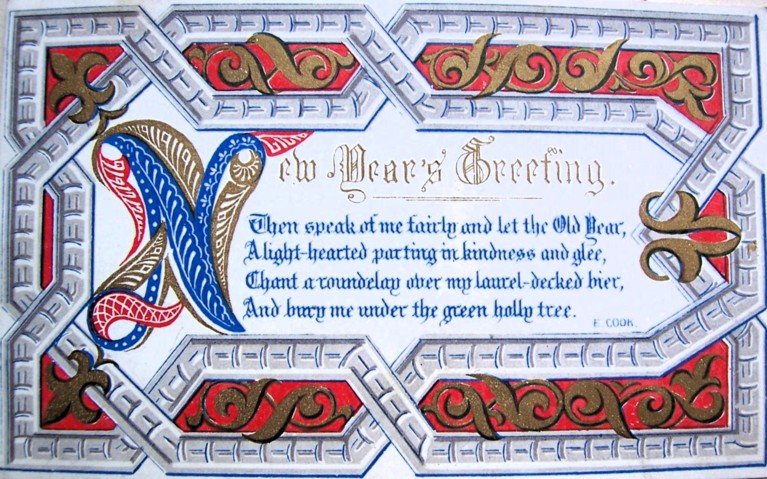

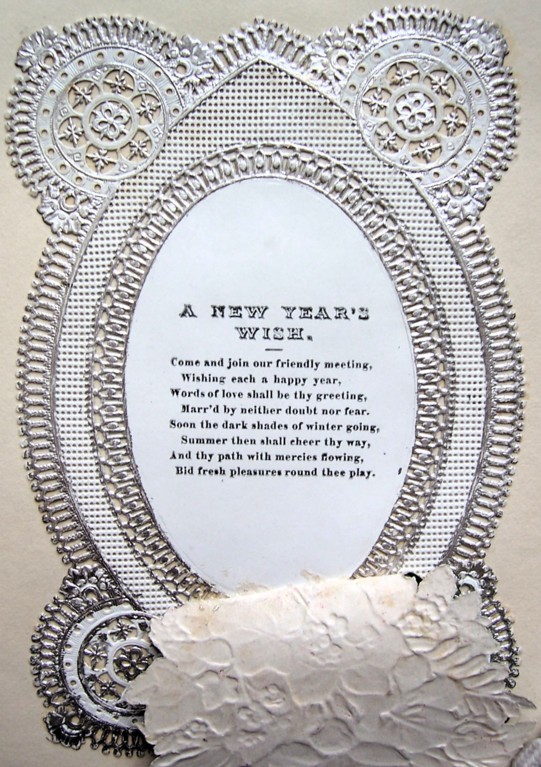

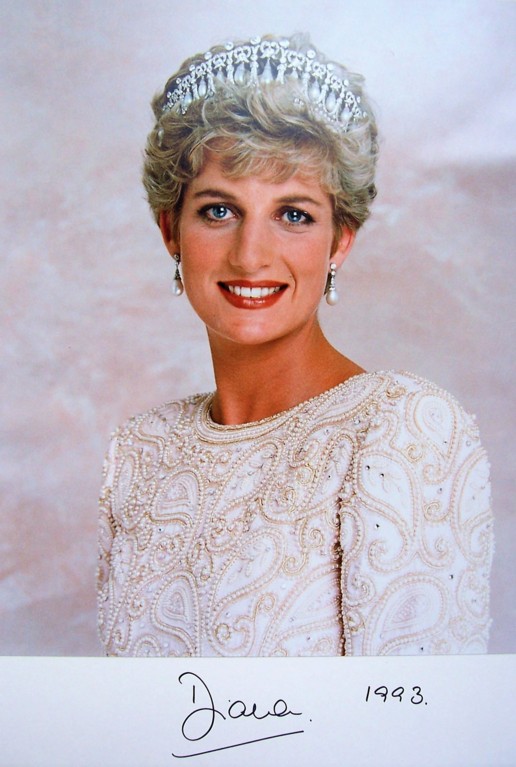

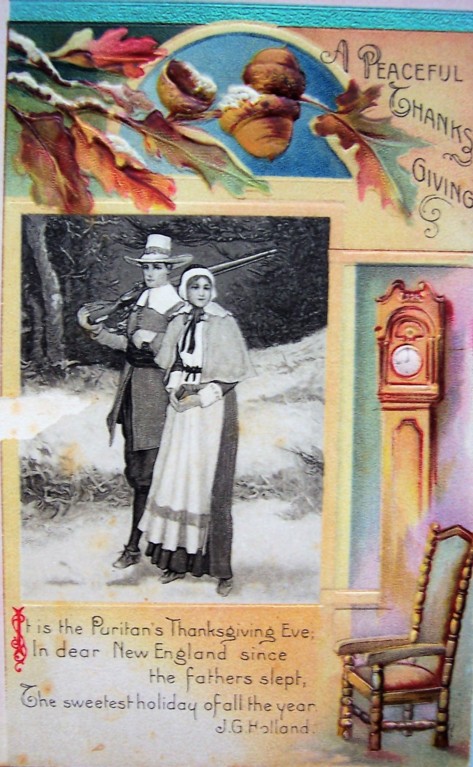

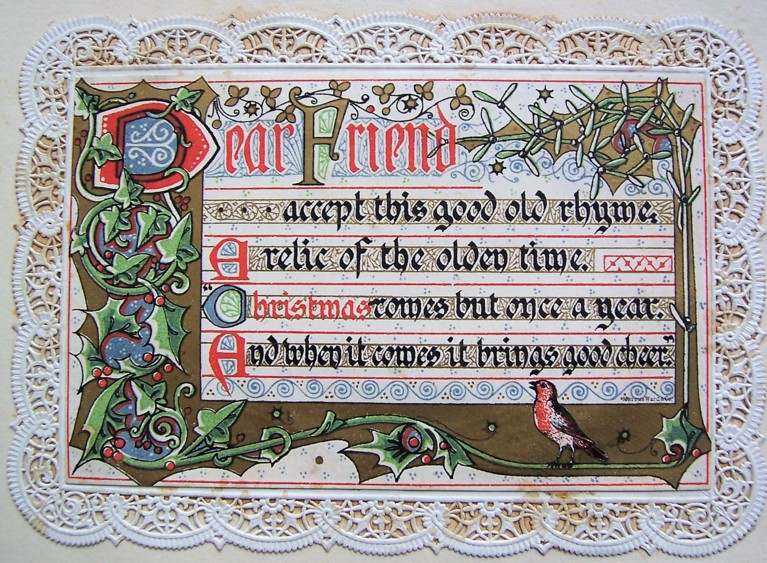

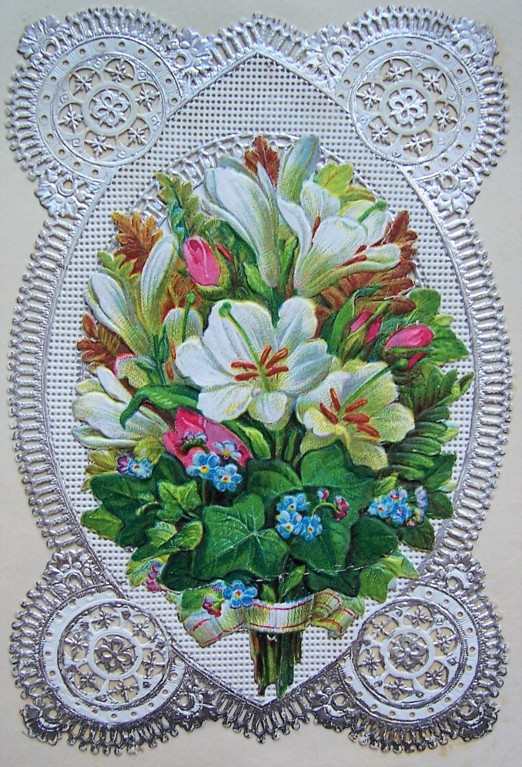

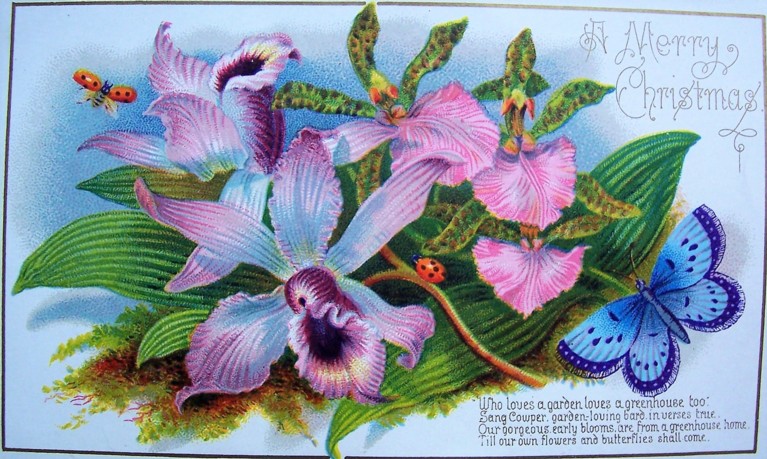

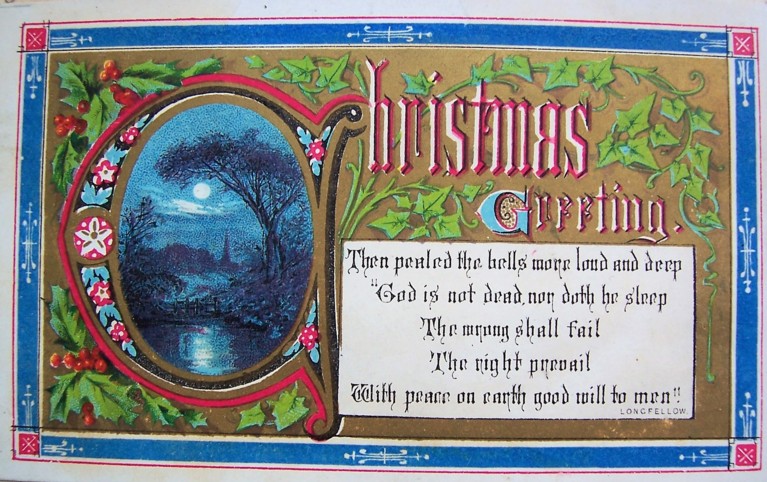

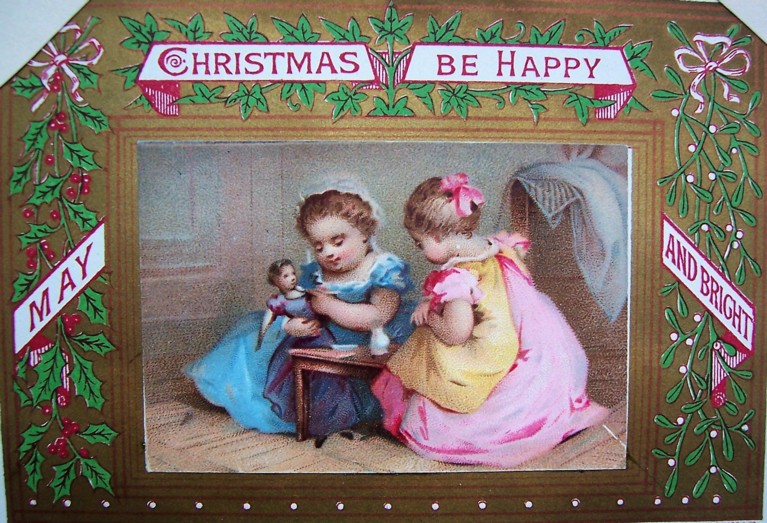

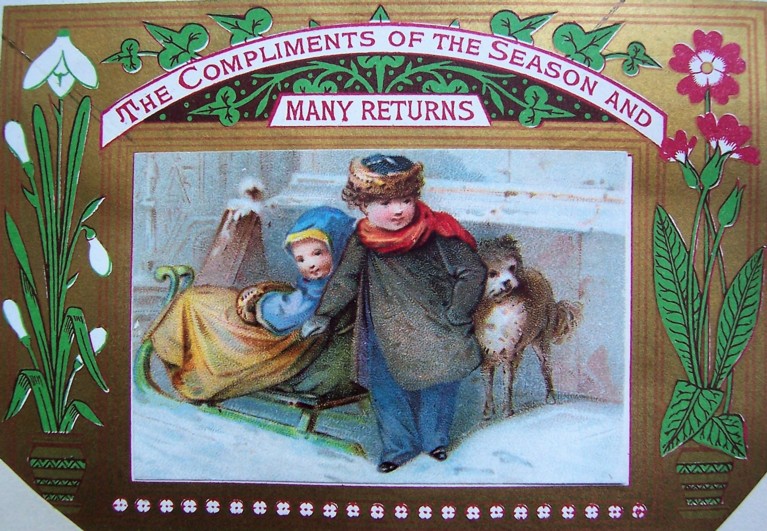

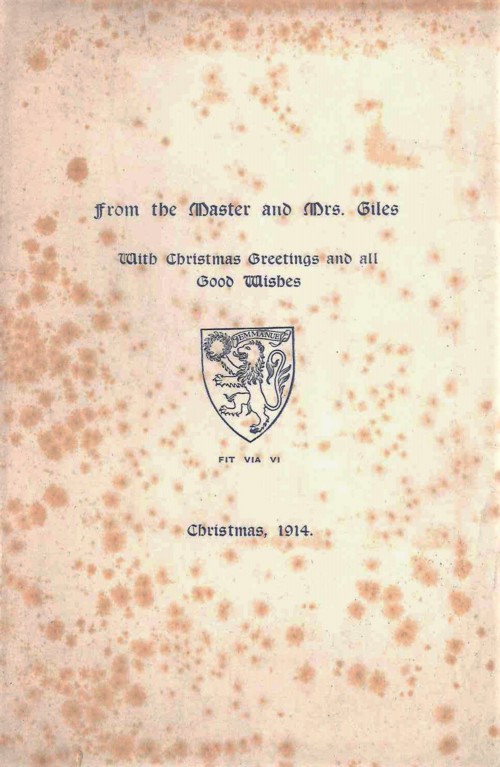

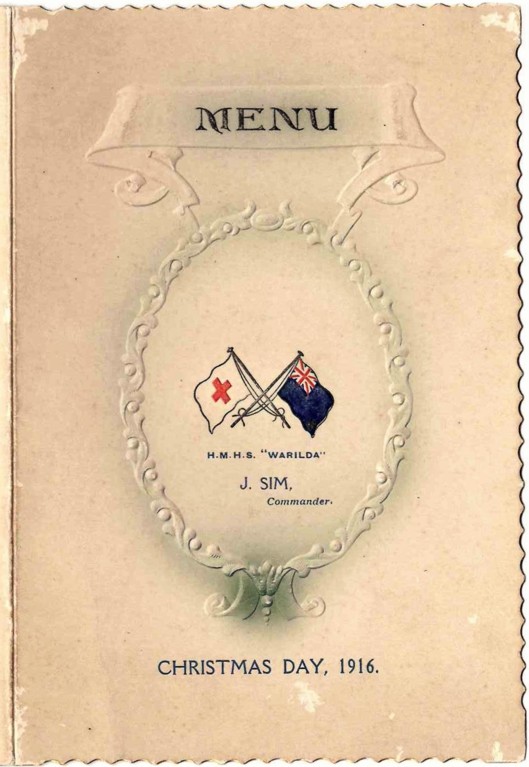

In some fascinating Victorian scrap-books kindly presented to Emmanuel Library by Hugh Pearson (matric. 1987) there are mementos of travels in the form of prints of stately homes (Chatsworth, Goodwood, Lowther, Trentham) and of various foreign resorts (in France, Italy, the Rhine) that have been carefully stuck on to the album pages. There is also a collection of recipes that rather implies the compiler’s single-minded devotion to the traditional British pudding and its tastes and ingredients (with never a mention of chocolate). And there are Christmas and New Year cards, probably from the 1870s onwards, arranged and fastened on the scrapbook pages. All these cards are modest in size (often 10 x 8 cms), on a single flimsy piece of paper: they are not folded cards that stand up. There was a fashion for these greetings to be surrounded by paper borders pierced and patterned to resemble lace.

The familiar iconography of Christmas is already established here. There are snowscapes bristling with holly and holly berries, and robins are ubiquitous and unavoidable.

So much of this is still going strong today, and it is usually claimed that it was the Prince Consort who, by introducing various German Christmas customs into the Royal Family’s Christmas, thereby caused those customs to become fashionable, imitated, and duly established in the British Christmas. Those readers of this Victorian scrapbook who enjoyed looking back over the collection of past Christmas cards might also enjoy the ‘Prince Albert Pudding’ for which the album supplies a recipe. Note that, like many of the pudding recipes compiled in the scrapbook, this does entail a serious amount of boiling.

Prince Albert Pudding

½lb (half a pound) of flour; ½lb of butter; beat up well ½lb of loaf sugar sifted, ½lb of raisins chopped fine, 5 eggs, the whites whipped to a stiff froth, a little candied lemon peel.

Steam it 3 hours. Served up with custard sauce.

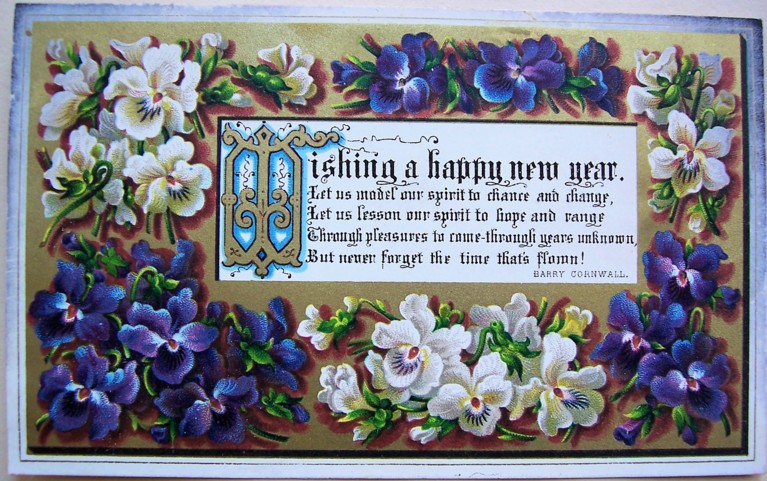

Some of the Christmas and New Year cards largely consist of some lines of rhymed seasonal greetings, with the text displayed in an ornamental border. The greetings tend to the earnest and uneffusive.

Those high-minded Victorians who sent and appreciated receiving such greetings cards might also appreciate the sobering implications of ‘Half-Pay Pudding’, for which the scrapbook’s recipe rules out all light nonsense but the essentials.

Half-Pay Pudding

¼lb of raisins, ¼lb of currants, ¼lb of chopped suet, ¼lb of flour, ¼lb of breadcrumbs, ¼lb of sugar. Pinch of salt. Without eggs. Boil for 4 hours.

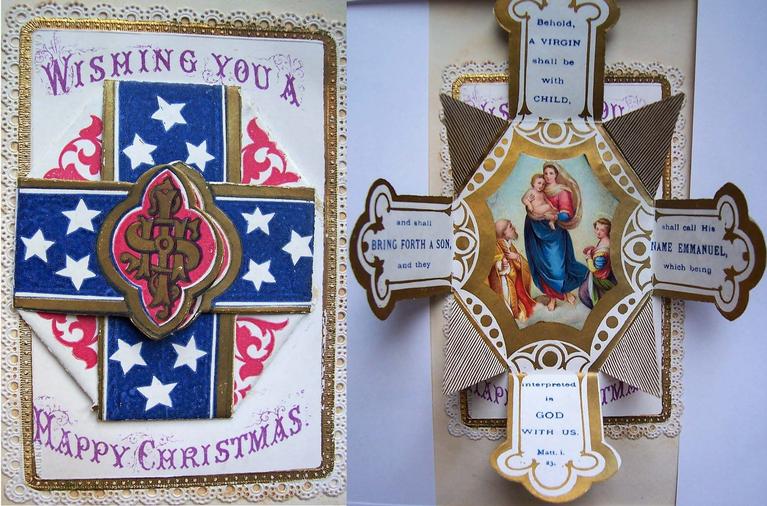

Many cards feature a lift-up flap, where part of the design is hinged to lift up and reveal a Christmas or New Year greeting printed underneath.

But at least in the selection preserved by this scrapbook, references to the Christian significance of Christmas are understated or absent altogether, and this example is an exception.

The figure of the evangelist, holding book and quill, lifts up to reveal underneath an intricate design of text and ornament, where the Gospel text of the message from the angels (above) to the shepherds (below) appears in red text on ribbons woven clockwise into the design. The makers of this scrapbook who also preserved a recipe for ‘Paradise Pudding’ seem intent on catering to a more material experience of heavenly sweetness.

Paradise Pudding

Six oz (ounces) of breadcrumbs, six oz of sugar, six oz of currants, six apples grated, six oz of butter beaten to a cream, six eggs, a little lemon peel chopped, and nutmeg.

Boil in a shape, 3 hours. Serve with wine sauce.

As with Christmas cards today, depictions of wintry scenes on Victorian cards are implicitly celebrating Christmas as a refuge and respite from mid-winter cold, as in this sentimental snow-scene of small children warming themselves around a rustic’s blazing fire – a flap is hinged to lift up and reveal a Christmas greeting underneath.

Feasting at mid-winter on rich foods was a traditional defiance of the time of least light, most gloom, and dismal cold. The scrapbook includes no fewer than three different recipes for Christmas pudding, attributed to Mrs Bond, Mrs Fendall, and Mrs Sutton.

Mrs Sutton’s Christmas Pudding 1879

Chop very fine, 1½lb of suet, 2lb of raisins, 1lb of currants; 1lb of flour; ½lb of mixed peel; ½lb of moist sugar; ¼lb of breadcrumbs; 2 Captain biscuits grated; 1 rind of lemon grated; 1 tablespoon of mixed spice; 1 teaspoon of salt; 6 eggs. Mix with ½ pint of milk and a large glass of brandy. Boil for 6 hours.

There are predictably different twists on ingredients and quantities, with Mrs Fendall adding sultanas, chopped apples, orange peel, chopped almonds and making it two glasses of brandy as well as one of sherry. The recipes also differ over their recommended boiling times, which range between five and eight hours.

One curious aspect to us of these Victorian greeting cards is that there are almost as many New Year cards as Christmas cards in the collection – whereas sending a separate New Year card has become rather unusual – and that so many of the cards are not ‘Christmassy’ at all but feature posies of flowers.

But there was a whole language of meanings expressed through flowers and depictions of flowers, a language now barely remembered. The readers of this scrapbook who enjoyed the sweet confection of ‘Princess Louise Pudding’ would not have been aware of the venturesome extramarital love-life of Queen Victoria’s artist daughter, Princess Louise.

Princess Louise Pudding

1 pint of milk poured over ½ pint of grated bread, the rind of a lemon grated; 3 oz of sugar; the yolks of 2 eggs well beaten. Mix all well & bake in a pie dish for ¾ of an hour, then cover the top with a thin layer of jam. Whisk the whites of the eggs to a stiff froth with 3 oz of powdered loaf sugar, and the juice of ½ the lemon, and put over the jam. Bake 5 minutes.

But they evidently enjoyed the scrapbook page where a rose on a hinged flap lifts up to reveal the ringleted sweetheart underneath.

The verse below reads: I wish I were a little bee, | To improve each shining hour. | I’d gather HONEY all the day | From such an … opening flower’.

A merry Christmas and a happy new year to all our readers! Very best wishes also to Dr Helen Carron, who has produced all the images for these blogs since their inception during the first lockdown, and who retires this month as College Librarian after 26 years of devoted service to the College Library and to generations of its student users.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

20 December 2023

View of the College Gardens, 1891

View of the College Gardens, 1891

This intriguing photograph, showing the Paddock under a fairly substantial dusting of snow, bears a one-word endorsement: ‘1891’. It might be supposed, then, that it was taken either in the very cold January of that year, or else in early March, when many parts of England suffered exceptionally severe blizzards. On closer inspection, it is apparent that the photo must date from much later in the year.

For one thing, the striped lawn indicates very recent mowing, which is not a normal feature of winter or early spring horticulture. For another, several circular beds of flowering tulips are visible. The deciduous tree to the left of the pond, moreover, is in full leaf, accompanied by what looks like blossom. A 1937 tree-plan of the college grounds identifies it as a horse chestnut, which normally flowers in May. True, the elms in front of the Hostel are still bare, but that tree comes into leaf rather late.

Meteorological records show that after an extremely warm spell in early May 1891, a sudden and dramatic change in the weather pattern resulted in snow and hailstorms afflicting much of the country on the 17th of that month (Whit Sunday). On the following day, eastern England experienced a particularly heavy fall of snow, some parts of Norfolk having as much as seven inches. A thaw set in within a day or two, so it can be safely assumed that this snowy photo of the Paddock was taken during the Whitsun weekend. The college sporting clubs’ reports in the 1891 Magazine make no mention of the mid-May snowfall, doubtless because of its brevity, but they do record that no rowing or football had been possible for much of January, ‘owing to the long spell of frost’.

The ‘Whitsun’ photographer may well have been Alfred Rose, Emmanuel’s Bursar, who was an enthusiastic amateur snapper. His plate-glass negatives, which are an invaluable visual record of the late-Victorian and Edwardian college, are preserved in the college archives. The photo is evidence that the freak Whitsuntide weather had taken Emmanuel’s residents by surprise, as many of the Hostel windows are wide open. Incidentally, the building adjoining the Hostel was the remaining portion of the straggling range of stables and outbuildings, including a coach house, that had for many years run along the college’s eastern boundary. The single-storey gabled projection is marked as ‘Engine’ on a plan of the college dated 1885, so it was presumably a boiler house; a coal yard was situated nearby. This building and the rest of the outhouses were all demolished in 1893, when the Hostel was extended.

It is interesting to note the steep drop of the ornate iron palings into the western end of the pond. Unlike the railings that ran along the Front Slips, they were not sacrificed to the war effort in the 1940s but remained in situ for another decade. The high fencing beside the path on the right of the pond is probably designed to deflect tennis balls, as the southern part of the Paddock was always marked out for lawn tennis in Easter Term. The protection provided by the fence was no doubt appreciated by the pair of swans that were the pond’s most important residents. The small white shape that can be seen near the pond outfall may be one of these birds. The monkey-puzzle tree, near the chapel, although appearing to be a youngish specimen in 1891, does not appear on the 1937 tree-plan, and the horse-chestnut tree, mentioned earlier, was felled in 1952. The fate of the elms needs no elaboration.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

30 November 2023

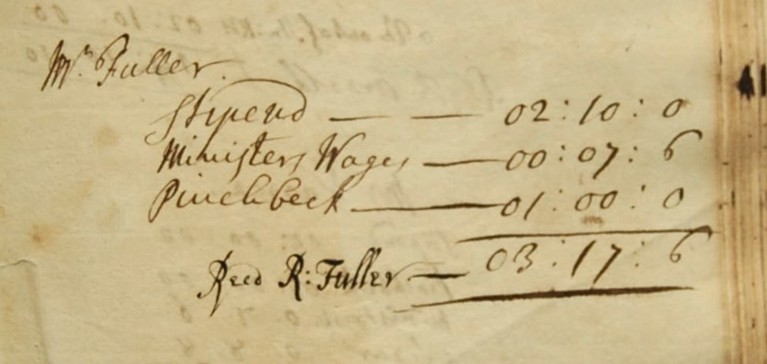

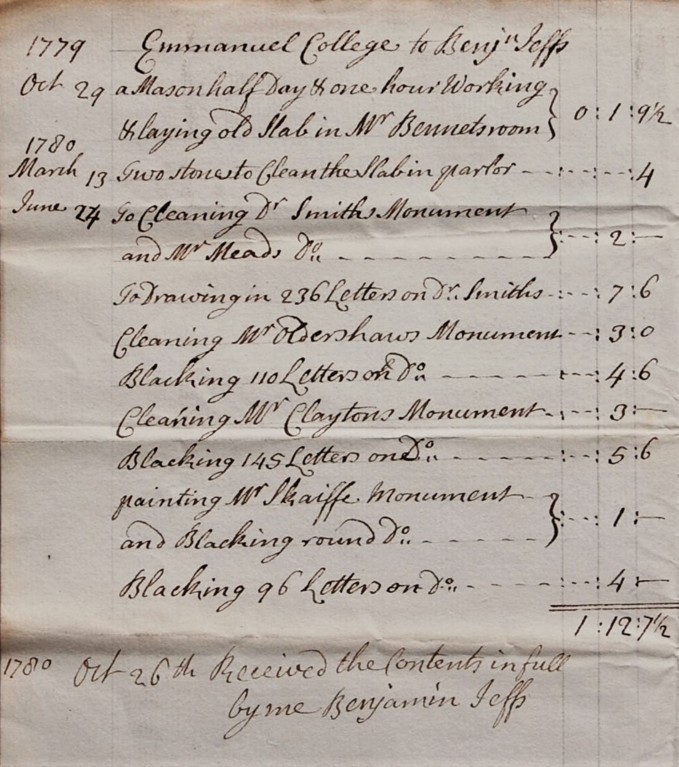

Robert Fuller signs for his final salary payment, October 1727

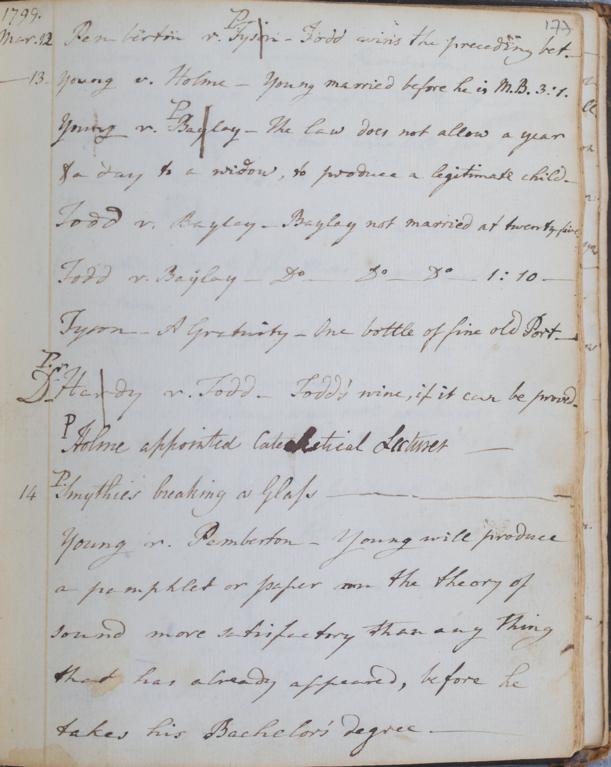

Emmanuel is almost unique among Cambridge colleges in having in its archives a disciplinary, or ‘admonition’ book, dating from the earliest days of the college. Most of the miscreants who feature in it are students, but two entries involve a college Fellow, the Revd Robert Fuller.

A native of King’s Lynn, Fuller was a graduate and, from 1719, Fellow of Emmanuel. He was ordained four years later. The first intimation of his contrariness is an entry in the admonition book dated 24th August 1725: Mr Fuller, Sen[ior] Fellow, & Dean of the College was Admonish’d by the Master in the presence of all the Fellows then in College for great offences that he was guilty of’. While it is startling to see a formal censure being applied to a member of the fellowship, the fact that Fuller was also dean does not exacerbate the scandal, as the office was held in annual rotation by Fellows who were in holy orders.

What might Fuller’s unspecified offences have been? He was frequently absent from college, as the exeat book attests, although his trips were generally of short duration. In the early years of his fellowship he preached regularly at Holy Communion services in Emmanuel’s chapel, but ceased to do so in May 1725 - doubtless evidence of a deteriorating situation. In February 1726, six months after Fuller’s first admonition, the college passed an order that ‘whoever misses his turn of visiting as appointed by the Dean shall forfeit the sum of five shillings to be deducted out of his stipend… and applied to the use of the Poors Bag’. Two months later, Fuller was fined under the terms of this somewhat opaque order.

Matters finally came to a head on 11 November 1726, when Fuller was summoned to ‘appear before the Master & Senior Fellows & Dean, and the Master proceeded to Admonish him for his irregular behavior & notorious neglect of duty. Upon this Admonition, he behav’d himself in a very insolent outrageous manner: & upon the Master’s testimony that he admonished him according to the direction of the statutes; he reply’d A fart for your Admonition & used other contemptuous language’.

Following this unedifying scene, Fuller appears to have gone out of residence almost immediately. The college statutes laid down that a Fellow could be deprived of his office after two (unheeded) admonitions, but in the event Fuller jumped before he could be pushed. A curt entry in the exeat book records that in June 1727 his name was ‘cut out’, a marginal note adding: ‘Marry’d June 11th 1727’. As Fellowships were forfeited upon marriage, Fuller’s college career was thus abruptly terminated. He returned to Emmanuel to collect his final instalment of wages at the Michaelmas 1727 audit, and doubtless never set foot in the place again.

Robert Fuller’s armigerous gravestone

Robert Fuller’s armigerous gravestone

What Fuller did for the next few years is unknown, but in June 1732 he was appointed Rector of Water Newton, Huntingdonshire. He died there some three years later, aged 39, and was buried in the chancel of the church. His gravestone records that he was formerly a Fellow of Emmanuel. Jane, his widow, shares his grave, and their daughter and ‘heiress’ Jane, who died in 1805, lies next to them. There are also nearby memorials to two other probable daughters of Robert and Jane: Easter Fuller (d.1759) and Mary Edwards, nee Fuller (d. 1801). It is to be hoped that the Revd Robert conducted himself in a more seemly fashion at Water Newton than was the case at Emmanuel – although it would be fascinating to know his side of the story!

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

30 November 2023

The garden team have endured an extremely wet and mild autumn so far. The mild temperatures have meant that the leaves are still hanging on the trees, meaning that the team are playing catch-up this year.

Leaf clearing is always the biggest task of the year for the team; it usually takes about three months of solid clearing to get the job done. Many leaves that we collect are then composted on site. The ability to be able to compost debris is a fantastic way of gardening sustainably. The more we compost on site means the less we must pay to be taken off site. The more composting we do, the less compost we must buy later.

The garden team can produce our own blend of compost to be used in the greenhouse for growing our plants and seedlings. We can also produce enough compost to dig back into the borders and to use as a mulch to feed our trees with. In turn, this reduces the need for artificial fertilisers and gives us a much more organic approach to gardening. Are the months of hard work worth it? We think so.

The beauty, though, of working in the gardens at this time of year is the wonderful autumn colours of the leaves. On a clear and sunny day, the leaf colours pop. The ginkgo tree in the Fellows’ Garden gives off a wonderful golden hue in the late afternoon sunshine. This is something that I can see daily from my office daily. What a treat!

Other areas of beauty include Chapman’s Garden. The colours from the Dawn Redwood, the tulip tree and the sweet gum tree looked magnificent. The Oriental plane tree in the Fellows’ Garden is always the last to fall. We will still be clearing the leaves on that right up to Christmas, and maybe beyond.

The Head Groundsman at the sports ground, along with myself, took delivery of a new piece of machinery recently. The college purchased a new Verti drainer to enable us to aerate all the college grounds and lawns. This should help improve the drainage and allow for better grass root growth in general. This is something that will hopefully help us return tennis to the paddock in the future.

Other jobs over the past month have included bulb planting, with additional shrub planting under the walnut tree by the library entrance. As a result of less traffic in the library car park, we were able to plant extra plants to tidy the area, hopefully without being driven over. This was the case in the past and hopefully the plants can correctly establish this time around.

The main project on my mind now, though, is drawing up some plans for the proposed Community Garden at the rear gardens in Park Terrace. We are very much at the early stage of this project, which will enable students, Fellows and staff the opportunity to have a space to garden within the grounds for general well-being. Watch this space for more details in 2024.

Best wishes.

Brendon Sims, Head Gardener

1 November 2023

October came and went in a flash. Although technically autumn, the temperatures remain mild compared with the average temperatures for this time of year. October also saw some significant rainfall. Although it wasn’t a consistently wet month, the rainfall, when it did come, was extreme.

It has felt that the gardening calendar year has been having a go at redressing the balance from the drought year of 2022. The grass (and weeds) has continued to grow and the window boxes that were put out in May continue to flourish with the bright pink flowers. It has been a funny year but a welcome one.

October is a time when it is perfect for major lawn renovation. This month sees the Front Court lawn undertake some needed TLC. It is the month that the whole team ascend the Front Court lawn to scarify, top dress, aerate and re-seed the lawn. I am always amazed at how much thatch (dead and living material that lies between the soil and the top level of the grass shoots) is removed from the lawn. A scarifying machine is passed over the lawn to remove the thatch in multiple directions and rakes out several cubic meters of debris. The process allows for better drainage. The team also aerates the lawn to relieve compaction from the summer months before top dressing with a sand/loam mix. The top dressing is distributed and levelled before the final task is to overseed.

The final appearance always looks extremely harsh, but the lawns soon bounce back to good health. It will need a few weeks to recover before we add organic fertiliser to help carry the lawn through the harsh winter months until the spring, when the grass will start racing away again.

October has also seen the department busy bulb planting for the spring bulbs. Most of our efforts have taken place on the new build planting beds. Front Court lawn quadrants have seen the amaranthus and geraniums replaced by the new tulip bulbs for the spring - we will be excited to see the results of our labour then.

September and October have also seen the Garden Team prepare the wildflower meadows for the spring. Extra yellow rattle and wildflower seeds have been sown in the Park Terrace meadows and the North Court meadows. Yellow rattle needs a period of harsh and cold weather to help with germination. The yellow rattle helps reduce the grass dominance and creates more space for other wildflowers to develop.

Our usual job of leaf clearing in October has been somewhat delayed this year. Due to the mild weather, the trees have been very happy to hold onto their leaves. The significant leaf drops tend to come after a heavy frost but, so far this year, we have only seen a one-night frost. Please spare a thought for our gardeners during this time of leafing season. We have many more weeks and months ahead of us, tirelessly repeating the monotonous task which is extremely hard work. Please give the team a smile and thank them if you see them. They will all appreciate a welcome comment.

This will be our task for the next few months ahead, although we do have some additional planting to look forward to (mainly in the new build areas) and, of course, some more bulb planting.

Best wishes.

Brendon Sims, Head Gardener

1 November 2023

Barnwell Hostel, from Midsummer Common

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the college’s acquisition of Barnwell Hostel. Purchased rather hurriedly as a stop-gap measure to help meet the college’s urgent need for more student accommodation, it turned out to be an excellent long-term investment.

At the end of 1952, the college learned that 43 Newmarket Road, a recently-vacated nurses’ hostel, was for sale. Erected in about 1907 on land owned by Jesus College, the property comprised a three-storey, ten-bedroom house, set in a large garden. The surveyor’s report commissioned by Emmanuel suggested that while the hostel was structurally sound, its ‘rather bleak nature, together with its situation, do not make it very attractive for normal residential or hotel use’; in other words, it might be got cheaply. The sale went through in June 1953 and the first Emmanuel students (all Freshmen) were installed at the beginning of Michaelmas Term. A married couple occupied the Warden’s flat as caretakers.

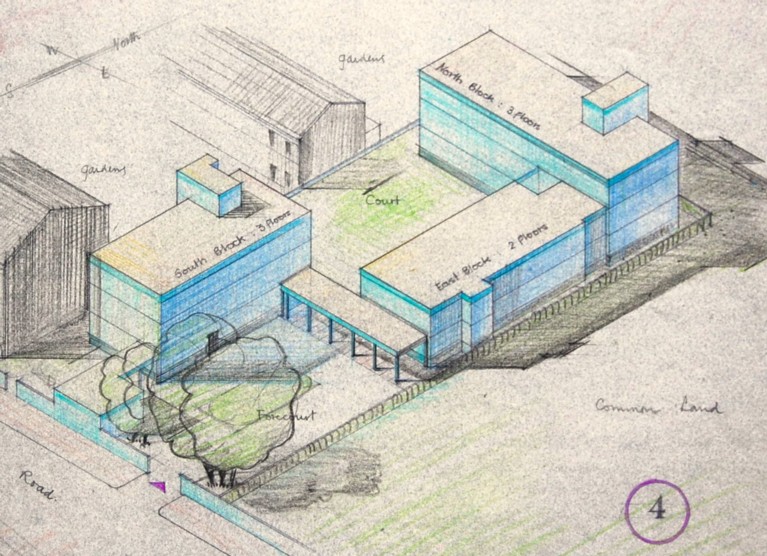

Richard Tyler’s unadopted design for Barnwell Hostel, 1959

It was soon realised that the site offered considerable potential for further development, and in 1959 the college engaged Bird & Tyler, architects, to design a new complex. Richard Tyler’s initial drawings, which envisaged the demolition of the Edwardian house and the creation of a three-sided court, were presumably in accord with his original brief. The college soon decided, however, that the existing building should be retained, so only the proposed L-shaped block was erected.

Tyler expounded his designs in the 1961/62 college Magazine: ‘As one comes into ‘A’ staircase one looks straight over Midsummer Common to the river through the tall bay window which runs from ground to roof…Staircase C also has a tall window running up two storeys, so that those who are young enough to bound up the first flight of stairs can enjoy the sensation of continuing into space beyond it’. Eschewing ‘pallid and off-white schemes’, Tyler chose natural wood fittings and ‘strong, clear colours’. The furnishings, which were ‘unaggressively up to date, designed for hard wear and the minimum display of dirt’, included flecked woollen upholstery and plaid curtains ‘where red merges into copper and green into blue’. Six extra-long beds were provided with Boat Club members in mind!

Not everyone shared the architect’s enthusiasm for the new block. A nearby resident complained bitterly to the Bursar of his shock at finding ‘a large building of no architectural merits at the bottom of one’s garden’. His principal grievance, however, was the severe impairment of his ITV signal. The college’s polite-but-firm response was that things would probably improve when the scaffolding was removed, but that, in any event, it had fulfilled all the council’s planning conditions.

Barnwell’s name plate

Cupola and weather vane

In November 1960, the college’s governing body agreed that 43 Newmarket Road and the new block were to be collectively known as ‘Barnwell Hostel’. John Reddaway, Fellow and later Bursar of Emmanuel, suggested that Will Carter, an acclaimed Cambridge craftsman, be engaged to carve a name plate for the Hostel’s boundary wall. After this ‘beautiful slate slab’ was vandalised in 1963, it was affixed, following restoration, to the south elevation of the Edwardian building, at a height which would be ‘out of reach to the smaller hooligans’.

In recent decades, the former caretaker’s flat has been reserved for married graduates, but it was only in 2013 that the entire hostel became a ‘graduate colony’. Given Barnwell’s peaceful ambience and semi-pastoral location, it is not surprising that the accommodation is rated highly by students. Although the building’s design is primarily functional, the panoramic staircase windows and eye-catching copper cupola (surmounted by a weather vane sporting the Emma lion) undoubtedly add a touch of distinction.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

1 November 2023

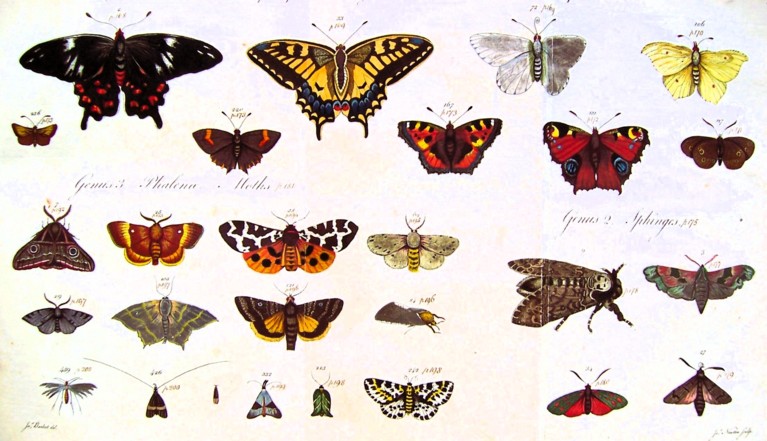

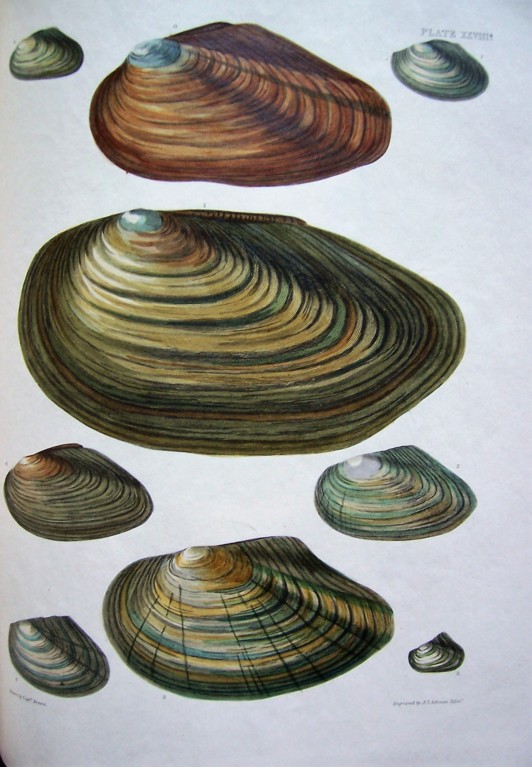

James Barbut, Les Genres des Insectes de Linne (London, 1781)

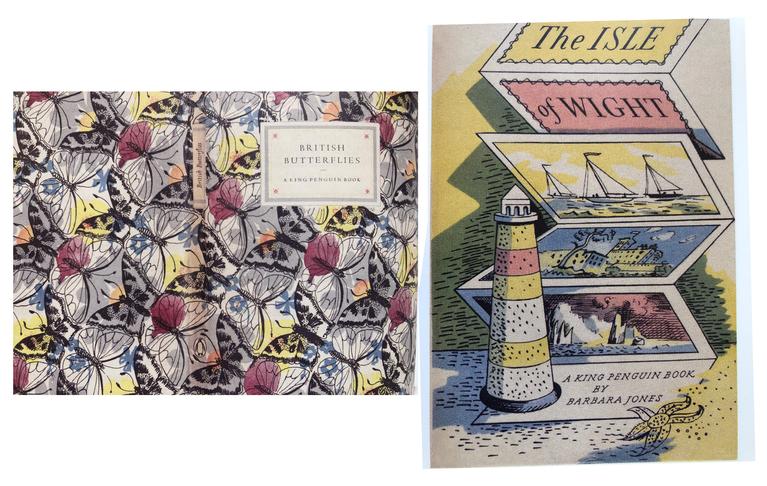

Now that we’ve said goodbye to the sight of butterflies for another year, the colour-plate images of their beauty in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century illustrated books – such as those in Emmanuel’s Library – are a potent reminder of their significance for so many past collectors and artists, and for those skilful individuals who managed to be both naturalists and artists. Across many cultures, the butterfly’s emergence from the chrysalis, and its ultimate derivation from a caterpillar, has symbolised transformation and rebirth, the triumph of spirit over the material and, in Christian tradition, the hope of resurrection. Yet there is always a painful sense too that the butterfly’s exquisite beauty is so evanescent.

Even the selection of illustrated books about insects in Emmanuel’s collection can represent the passionate interest, even ruinous obsession, of what we would now describe as amateur collectors of insect specimens. The earliest in our collection is Eleazer Albin (d. 1742?), possibly a German immigrant but by 1708 living in Piccadilly with his family. Initially a teacher of painting in watercolours, he became fascinated by natural history and published illustrated books on English insects, birds, and ‘spiders and other curious insects’. Albin prided himself on drawing specimens from life: his A Natural History of English Insects (1720) is ‘curiously engraven from the life: and (for those who desire it) exactly coloured by the author’. Albin’s illustrations of caterpillars munching on their favourite plants, attended by the moths that they become, are both elegant and skilful.

Eleazer Albin, A Natural History of English Insects (1720)

The text observes that the caterpillars who feed on the marsh plant fall off so often that they have developed a powerful backstroke to get them back to the plant stem. Albin acknowledges the participation of his daughter Elizabeth in drawing and painting for his A Natural History of Birds (1731-8), and appeals to fellow enthusiasts for more specimens: ‘Gentlemen … send any curious birds to Eleazar, near the Dog and Duck in Tottenham Court Road ... '

Albin, English Insects

Albin, English Insects

Moses Harris, The Aurelian (1766)

Another who combined skills as an artist and engraver with interest in natural history was Moses Harris, whose The Aurelian: or Natural History of English Insects appeared in 1766. Some of his illustrations are very accurately observed, and evidently coloured by Harris or under his close supervision. Stemming from his work as a colourist, Harris also propounded a system of colours through his ‘colour wheels’ that demonstrated how a range of colours may be made from red, yellow and blue.

The Cork-born Edward Donovan (1768-1837) rarely ventured outside London, yet he published on insects from across the world. Donovan was both artist and engraver, and (with a team of employees) also a colourist – as well as an ardent student of the natural world. As well as a sixteen-volume Natural History of British Insects (1792-1813), he published An Epitome of the Natural History of the Insects of China (1798).

Edward Donovan, Insects of China (1798), ‘Papilio Hyparete’, ‘Found near Canton’

Donovan, Insects of China, ‘Papilio Pryanthe’, ‘Papilio Philea’

Donovan also produced the first book on The Insects of India and the Islands in the Indian Seas (1800) and was the first to deal with the insects of Australia in his Insects of New Holland (1805).

Donovan, Insects of China, ‘Phalaena Bubo … Zonaria … Pagaria’

Donovan, Insects of India and Adjacent Islands (1800), ‘Papilio Ulysses’, ‘Dutch Spice Islands’ [Indonesia]

So how did Donovan do all this from his home in London? He was an avid collector and purchaser of specimens brought back by travellers – so much so that he even started his own Museum and Institute of Natural History, open to the public on payment of one shilling and displaying hundreds of cases of his specimens. Alas, the venture did not pay off, and Donovan’s pursuit of costly purchases of specimens so impoverished him that he eventually died penniless, leaving his large family destitute.

More successful in worldly terms was John Westwood (1805-1893), whose earlier amateur interests in both insects and in illustration later led to his becoming one of the first entomologists with an academic position at Oxford.

John Westwood, Oriental Entomology, ‘Papilio Icarius’, ‘Assam’; Butterflies ‘From the Torres Straits Islands’

But again, these splendid illustrations to his Cabinet of Oriental Entomology (1848) – ‘being a selection of some of the rarer and more beautiful species of insects, native of India and the Adjacent Islands' – are based on specimens in the collections of other naturalists.

Westwood, Oriental Entomology, Butterflies from modern-day Bangladesh

This was a collaborative fraternity of students of natural history, and Westwood collaborated with Edward Doubleday (1810-1849) on his Genera of Diurnal Lepidoptera (1846-50).

Westwood, Oriental Entomology, Butterflies found in the Himalayas

Edward Doubleday, Diurnal Lepidoptera, ‘Pavonia Rusina, Pavonia Ajax’

‘He had a butterfly mind’ is one of the less positive associations of butterflies, hardly shared by the extraordinary application of these various artists who were also students of natural history. Their lasting accomplishment in recording their butterflies is a kind of defiance of the evanescence of their subject.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

Images by Helen Carron, College Librarian

5 October 2023

Mrs Edward Bury, A Selection of Hexandrian Plants (1834), ‘Crinum augustum’. Bury was the artist but Robert Havell engraved and coloured the plates.

In any collection of nineteenth-century illustrated books such as Emmanuel is fortunate to possess, there will be ‘flower books’. A significant number of such books of botanical illustration are the work of largely unsung women artists, who display extraordinary painterly skills – as well as a reverent attention to nature – in so patiently recording their observations of plants and flowers. Often published anonymously and frequently sidelined, their work quietly advances a wider knowledge of botany, enlisting beauty in the greater understanding of nature (and in many cases also educating their readers in how to paint the same flowers and foliage for themselves).

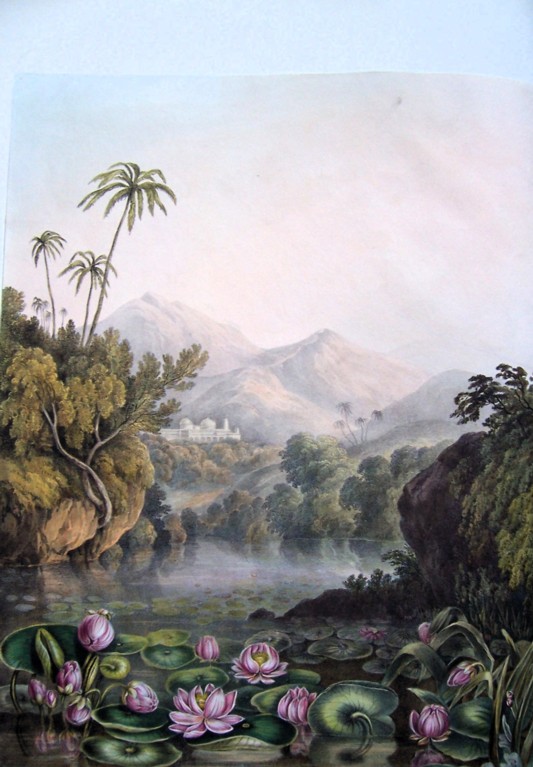

The stunningly large and brilliantly coloured lilies of Priscilla Bury’s Hexandrian Plants (1834) reflect contemporary excitement among plant collectors at such exotic new plant imports blooming in their hothouses in and around Liverpool in the 1830s. At much the same time, the Irish botanical artist Catherine Teresa Cookson (of whom little is otherwise known) catered to such a taste for exotic flora in her Flowers drawn and painted after nature in India (c.1835).

Catherine Teresa Cookson, Flowers drawn … in India (c.1835), ‘A View taken in INDIA, of the LOTUS growing in water’

Cookson, ‘The White Plumieria’

But the impetus to teach a book’s users how to undertake botanical illustration for themselves will tend necessarily to focus on more accessible flora. The splendid illustrations in Studies of Flowers from Nature (1818-1820) by ‘Miss Smith’ are accompanied on the facing page by helpful instructions on the particular paint colours to be used in copying the image. A second set of flowers drawn only in outline is also included for colouring in. Like a number of other female botanical illustrators, Miss Smith dedicates her book to a female patron, George III’s daughter Princess Elizabeth, herself an accomplished artist. Miss Smith has never been identified but may have been a teacher in a girls’ boarding school near Doncaster.

Miss Smith, Studies of Flowers from nature (1818-1820), ‘Camellia’

Anne Everard, Flowers from Nature (1835), ‘Purple foxglove’

Anne Everard’s Flowers from Nature … with Instructions for Copying (1835) also accompanies its thirteen hand-coloured lithographed plates with precise directions. For the purple foxglove: ‘Damp the paper with warm water and shade the corollas with a mixture of Prussian Blue and Lake; put a wash of carmine over them, and when nearly dry another of cobalt …’ (and so on for another eight lines of print).

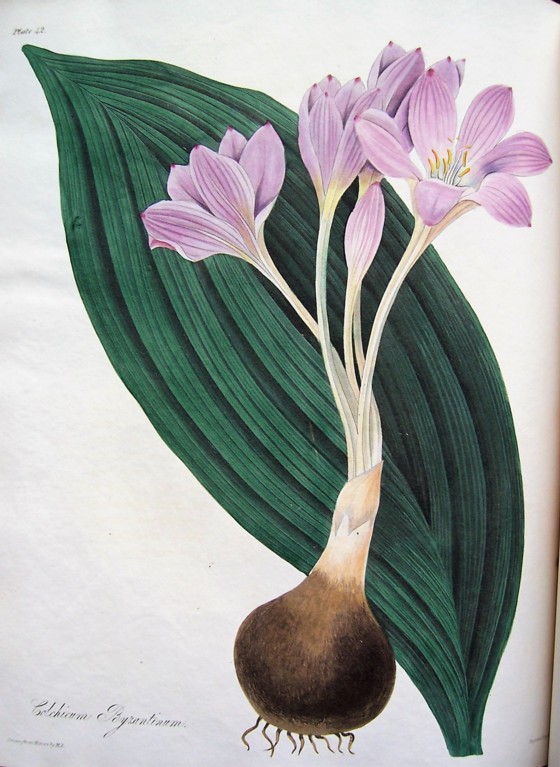

Some women artists left their drawing and painting to be engraved or lithographed by men, as with Margaret Lace Roscoe’s Floral Illustrations of the Seasons (1831), ‘From Drawings by Mrs Edward Roscoe’.

Margaret Roscoe, Floral Illustrations of the Seasons (1831), ‘Colchicum byzantinum’

But other women artists engaged in, and hence controlled, the whole process themselves, as is shown by two illustrated books themed around the flowers that are mentioned by celebrated poets. In her The Flowers of Milton (1846) Jane Elizabeth Giraud is building on the success of her The Flowers of Shakespeare a year before.

Her method was to draw the originals, then have them lithographed, and finally hand-colour the lithographs herself.

Jane Elizabeth Giraud, The Flowers of Milton (1846), illustrating lines from Milton’s ‘Lycidas’ that mention the musk rose, woodbine, cowslip and daffodil

Elizabeth Bartlett, The Flowers of Scott (1852), illustrating lines from Sir Walter Scott’s ‘Marmion’ mentioning the water flag and rush

In Elizabeth Bartlett’s The Flowers of Scott (1852), thirty-five lithographic plates illustrate flowers that occur in the poems of Sir Walter Scott, and Barlett indicates on each plate that she has both drawn and lithographed them (‘E.B. delt. et lith.’).

Anonymous publication by women artists is well exemplified by Ten Lithographic Coloured Flowers by a Lady (Edinburgh, 1826-1832). This is actually forty fine plates published in four sets of ten. The list of subscribers – headed by the Duchess of Hamilton and the Lord Provost of Edinburgh – is entirely Scottish, but the ‘Lady’ artist remains anonymous to this day.

Ten Lithographic Coloured Flowers by a Lady (1826-32), ‘Primula auricula’

Rebecca Hey, The Spirit of the Woods (1837), ‘Mountain Ash’

In Rebecca Hey’s The Spirit of the Woods (1837) the title page makes no mention of Mrs Hey by name, although the preface refers to its author as female. There are 26 hand-coloured plates, presenting what is one of the early encyclopaedias of wild trees. Her earlier The Moral of Flowers (1833) acknowledged that the drawing and engraving had been done by men, but here are emphasized ‘the drawings for the illustration of the work, which the author herself has ventured to execute from nature and which she trusts will be found botanically correct’.

A prolific woman author and illustrator on botanical subjects was Jane Loudon (1807-1858), although before she started on that career she had already published, aged only 20, a novel that is sometimes seen as a pioneer and precursor of science fiction: The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827). (Reader, it’s a reincarnation of the Pharoah Cheops, not a dystopian matriarchy). Having reviewed The Mummy! John Claudius Loudon, the celebrated (and much older) Scottish garden designer, horticulturalist and author sought out the author of The Mummy! and they married six months later. Spotting a gap in the market for accessible books about how to garden, Jane Loudon’s books were illustrated with her own botanical paintings, which show a strong feeling for both colour and detailed botanical record.

Jane Webb Loudon, The Ladies Flower Garden of Ornamental Perennials (1846), ‘Peonies’. Loudon’s page layouts modelled on a bouquet were imitated and influential on décor.

Ladies Flower Garden, ‘Campanula’

These gardening books, directed at female readers, empowered countless women to take possession of their worlds through the creating of their own gardens, inspired by the information and the compelling illustrations in Mrs Loudon’s books. Eleven such books were published, and she also founded The Ladies Magazine of Gardening in 1842.

Jane Webb Loudon, British Wild Flowers (1847), a selection including ragwort, chamomile, yarrow, knapweed, musk thistle, hawkweed, succory

Fanny Elizabeth de Mole, Wild Flowers of South Australia (Adelaide, 1861), ‘Westringia rosmarinifolius and Cheiranthera linearis’

Jane Loudon’s sheer productivity in her life of only fifty years is astonishing, while in a much shorter life Fanny Elizabeth de Mole (1835-1866) produced the first book recording the flora of the South Australia colony. Her line drawings were sent to England for lithographing and the plates then returned to Australia, so that Fanny could colour by hand the one hundred copies each containing twenty plates.

‘Man … cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower’, in the words of the funeral service in the Book of Common Prayer. Part of the fascination of these books is that they preserve enduringly the beauty of flowers that so soon will have faded and represent the skilled life’s work of many undervalued women artists.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

Images by Helen Carron, College Librarian

4 October 2023

Ram’s horn snuff mull, given to Emmanuel in 1856

Emmanuel has for some time been officially a ‘smoke-free site’. Anyone wishing to enjoy a crafty ciggie is therefore obliged to skulk outside the college gates. Yet for nearly four centuries, smoking within the precinct was not just tolerated, but practically encouraged.

An early Emmanuel enthusiast for the weed was Elias Travers. Appointed Fellow in 1609, he had tutorial responsibility for a student named Thomas Knyvett, who was admitted in 1611, aged 16. When Thomas’s grandmother received a tip-off that her pet tutor indulged in the vice of pipe-smoking, she immediately threatened to send her grandson to another college. Travers did not want to lose Lady Knyvett’s generous, if demanding, patronage, so he gritted his teeth and replied: ‘if the Tabacco I have sometimes taken be a just grievance to any, I desire them to know that if the forbearance or utter avoidance of it will give them content, I shall quickly quite ridd myself of it…’. Whether or not Travers genuinely intended to abjure the pernicious habit, his renunciation was enough to placate Lady Knyvett, who let Thomas remain at Emmanuel.

It was not long before smoking became an integral part of Emmanuel’s society. From 1710, and probably earlier, tobacco was supplied gratis to the fellowship on high days and holidays, as well as at the annual audit. College orders of the 1720s required the steward and dean to provide the Parlour with ten quarts of red wine and half a pound of tobacco on the day of their election. This obligation proved predictably unpopular, and the orders were quashed in 1747. Certain standards were maintained: partaking of snuff during dinner in Hall, for example, was forbidden by a ruling of 1782, any Fellows transgressing being fined one bottle of wine ‘for every pinch’.

The Parlour wager books record several bets involving tobacco, including whether its smoke could ‘take fire’, the likely interval between using snuff and sneezing, the probability of an ounce of tobacco filling five pipes, and how many (if any) bishops smoked. A truly bizarre wager between Henry Homer and William Meeke in 1783, was whether ‘Homer’s Mare smoakes a pipe backwards better than Meeke forwards’.

A variety of smoking accoutrements were procured for Parlour use, including tobacco boxes, spitting trays, and, in 1766, two gross of ‘Glaz’d Tobacco pipes’. A ‘Polished Tobacco pot & rais’d cover’, engraved with the college arms, was commissioned in 1784 - but mysteriously vanished from the Parlour cupboard in 1800. Later acquisitions included a ‘handsome’ gift in 1798 of a ‘canister of prime snuff’, a bejewelled ram’s horn snuff-mull given in 1856 by William Paley Anderson (one of the younger Fellows), and, in the last century, silver cigarette boxes, ashtrays and matchbox cases, all of which are now rapidly acquiring curio status.

Smoking Concert programme, 1961

Matchpot with Emma crest

Undergraduates seem always to have been at liberty to smoke, hence the need for the University authorities to threaten students with expulsion if they did so anywhere near the tobacco-hating King James I and VI, during his December 1624 visit to Cambridge. By the nineteenth century Cambridge shopkeepers were supplying a plethora of mass-produced tobacco jars, ashtrays, cigarette cases and Carlton Ware matchpots, which students could customize by having their college’s coat of arms added. A popular form of undergraduate entertainment was the so-called ‘Smoking Concert’, traditionally confined to male audiences. Emmanuel’s Musical Society hosted many such events, but the last of these fuggy recitals was held on 12 March 1962. Just a few days earlier, the Royal College of Physicians had published its groundbreaking report on the health risks of smoking. Change was in the air…

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

3 October 2023

Welcome back to the news from the gardens. I welcome all the new freshers, fellows and post-docs to the blog. It is my intention to keep you all updated with the comings and goings from the department, the successes and the disappointments, the good, the bad and the ugly.

The department has been stretched as always since the last blog. It has been a very busy growing year in general. This is the complete opposite to one year ago when the department had witnessed a very challenging year due to the extreme hot weather and the droughts. This last calendar year has been kinder to us. The temperatures, although mild, have not been blisteringly hot. We have had ample rain and warm temperatures, these themselves having added challenges. This year, the plants and lawns (and weeds) have seen phenomenal growth. It has been hard to keep up this year. Hedges have required cutting more frequently, lawns being tendered twice as often, climbing plants being trimmed with regularity that we have not seen in many years.

The department itself is in a healthy position, though. We do have our regular staff but also one full-time apprentice on the Cambridge Colleges Apprenticeship Scheme and a part-time student, retraining in horticultural from the WFGA.