Blog

28 May 2020

Readers of this blog are likely to have seen – whether in the libraries of country houses or educational foundations – libraries with walls lined with leather-bound books, sometimes with lavish gilt decoration. The bindings of early books are much studied by historians of the book, and Emmanuel has some choice examples. These begin with a copy of Theodore Beza’s theological treatises (Geneva, 1573), dedicated by him to Emmanuel’s founder, Sir Walter Mildmay, who presented it to the College – it is sumptuously bound by Jean de Planche. In 1659 Rachel, Countess of Bath, a great-granddaughter of Sir Walter and one of the College’s early women benefactors, bequeathed books to the value of £200, most of which are still in our library and with her armorial device gold-tooled on the covers.

But by what developments did the book as a bound item move from the leather-bound books of former centuries towards the utilitarian hardback of today? One of the nineteenth century’s most influential legacies to the history of book production is the cloth case. Ever since the Middle Ages, textiles had been used to cover bindings of manuscripts and books, but the velvets and silks used for this purpose were expensive and de luxe items, as with the Latin Bible in Emmanuel Library, bound in crimson velvet, which belonged to Edward VI. By contrast, the cloth coverings of the Victorian period were developed for their utility and cheapness, and lent themselves to the increasing mechanization of the book trade.

By the later eighteenth century, some types of coarse canvas were being used to cover school-book bindings since these items were subject to heavy use. But it was not until 1823 that a purpose-made, filled and glazed bookcloth was developed for covering cased-in books. It soon became the binding of choice, used ubiquitously by Victorian publishers. Bookcloth was much cheaper than leather, and much more durable than a paper covering. It could be produced in a wide range of colours and embossed finishes. It was also capable of taking detailed blocked impressions, stamped with a blocking press rather than being built up by hand with individual tools.

The early decades of the nineteenth century saw new developments in the mechanization of the printing process. Developments of machines to speed up the binding process soon followed, making books much cheaper to produce. The cloth case was the ideal binding for use on such books, because the sewn textblocks and the cases could be prepared in separate processes and then simply pasted together at the end of the production line.

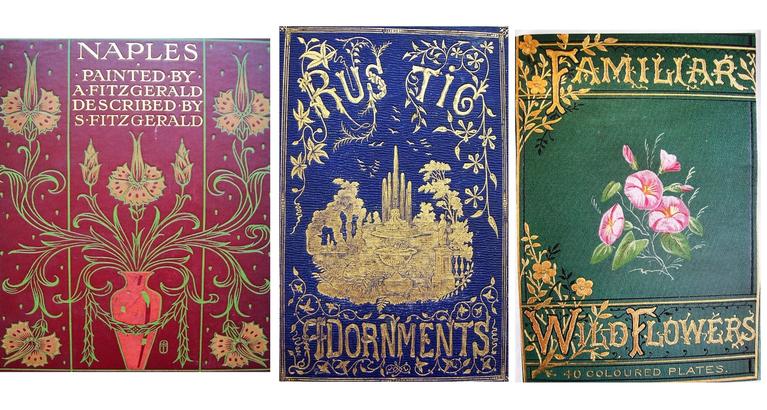

Such case bindings were certainly less robust than books from earlier centuries bound traditionally ‘in boards’ (that is, with the boards attached to the textblock before the book was covered in leather). But books in case bindings were affordable to a much wider range of people. So it was that a form of book binding that started as a mere temporary cover – designed to be replaced after purchase by wealthy customers with a smarter binding of their own choice – came to be accepted as a permanent form of binding. With this development, some bindings in bookcloth become lavishly decorated with gold and blind blocking, colour-printed designs, embossed patterns in the cloth, and elaborately shaped boards (as the two illustrated examples from Emmanuel Library’s collections demonstrate). The forerunner of today’s hardback books had been born.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

Images by Helen Carron (College Librarian)

Back to All Blog Posts